The kaleidoscopic world of Der Schmied von Gent

After his initial breakthrough with Der Ferne Klang in 1909, Franz Schreker’s successful opera career was about to crumble before his eyes. Rightwing hecklers marred the premiere of Der Schmied von Gent on 29 October 1932 in Berlin. Within a couple of years, the Austrian Jewish composer fell from being lauded as the future of German opera to having his ‘degenerate’ work banned and losing his prestigious teaching positions. He died in Berlin on 21 March 1934, two days short of his 56th birthday. Having been largely forgotten, Der Schmied von Gent was rediscovered in a Berlin State Opera staging in 1981. Opera Ballet Vlaanderen’s effervescent production presented in February 2020 marks merely the 4th modern performance of the opera.

There’s a delightful symmetry in the fact that the opera has arrived in the city in which the story is based. Schreker wrote the libretto himself. Based on the Belgian author Charles De Coster’s story, the plot is set in the 16th century, during the Spanish domination of Flanders. Transforming the old folk tale of Smidje Smee, Schreker showcased the cunning of the influential blacksmith Smee, who while dealing with the occupying force has never disowned his patriotic, freedom-fighting ways of yore. Schreker intended Der Schmied von Gent to be a novel type of folk opera, considering it to be ‘Brueghelian’ in scope. It truly parts with his earlier works which relentlessly charted the chasms of his protagonists’ psyche, preferring to plunge into a fairy tale world. Musically too, Schreker operated a late change of style, departing from his former post-romantic tendencies and embracing a plurality of influences ranging from New Objectivity and the zeitoper to neo-baroque elements.

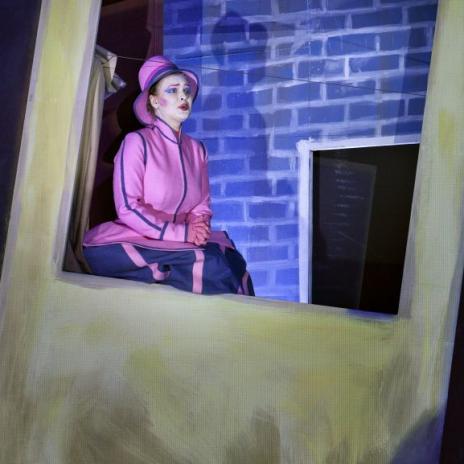

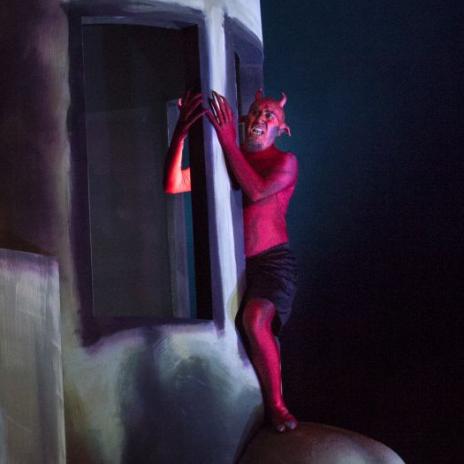

With his opera debut, German theatre’s enfant terrible Ersan Mondtag offers a graphic, dazzling interpretation in which Schreker’s stylistic versatility is met with hallucinogenic visuals. But do not be fooled by the expressionistic drollery: the vibrant costumes, the revolving stage depicting medieval Ghent on the front and a child-gulping demon on the back. The production does not shy away from sombre subject matters highlighting the darkest hours of Belgian history. Mondtag explains ‘There are many ways to look at Smee's story. He makes a pact with the devil, which makes him immensely rich in a short time. Then he doesn't want to pay the agreed price. That story is very similar to that of colonialism: acquiring wealth by robbing a country, then using that wealth to build, for example, a gigantic station - as happened in Antwerp - and never accounting for that transaction afterwards'.

Almost 240 years separate the 1648 treaties of the Peace of Westphalia, ending the Eighty Years’ War and finally recognising Dutch independence, and the Congo conference in 1884, which established King Leopold II imperial rule. And yet, the production raises the question of a connection between these two historic events. ‘Is it conceivable’, speculates the dramaturg Till Briegleb, ‘that the terrorization of Flanders during the Eighty Years' War is at the root of the almost eighty years of terror perpetrated by Belgium in Central Africa?’ Although an opera might not be able to answer such a complex question, Mondtag uses this welcome opportunity to highlight the lingering collective traumas caused by violence and repression.

Mondtag’s reading of Der Schmied von Gent as a heralding foundational fable of Leopold II’s exploitation of the Congo makes for a performance like none other. In the first two acts, he follows the libretto rather closely: despite tearing the plot from its historical context, the action is still visibly located in Flanders. However, the plot thickens in Act 3. Subtle allusions to African art flare up all of a sudden and Smee returns as the ghost of Leopold II. After his death, the hell he is sent to uncannily recalls the Congo. As evidenced by the unexpected interruption by Patrice Lumumba’s independence speech, the Congo is now free. Free to deny him access, so Smee has to retrace his steps. Instead, Smee-as-Leopold II ventures to heaven’s door. Warded off again, Smee finds himself running a waffle stand inside a museum. Contrite, he confesses his sins and is absolved, which takes on a different meaning when enacted by the Belgian king’s impersonator. Can absolution be this readily given, trauma this easily overcome?

The full performance is no longer available but other material about the production can be found here.