Conspiracies and regattas form the backdrop to the fortunes of a young singer. Harassed by a heartless spy, she sacrifices everything to save the man she loves and the woman he prefers over her.

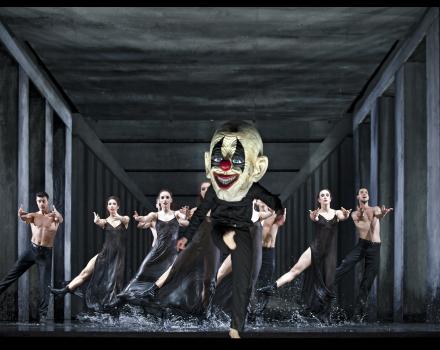

Ponchielli based his opera on Victor Hugo’s play Angelo, tyrant of Padua. An expert on Hugo, director Olivier Py offers us a dream-like version of this dark Romantic tragedy, presided over by sex and death. Paolo Carignani conducts an exceptional cast in the six demanding main roles.

Cast

La Gioconda | Béatrice Uria-Monzon |

|---|---|

Laura Adorno | Silvia Tro Santafé |

Enzo Grimaldo | Stefano La Colla |

Barnaba | Franco Vassallo |

La Cieca | Ning Liang |

Alvise Badoero | Jean Teitgen |

Isèpo | Roberto Covatta |

Chorus | Chœurs de la Monnaie, Académie des chœurs de la Monnaie s.l.d. de Benoît Giaux, Choeurs d’enfants et de jeunes de la Monnaie s.l.d Benoît Giaux |

Orchestra | La Monnaie Symphony Orchestra |

| ... | |

Music | Amilcare Ponchielli |

|---|---|

Conductor | Paolo Carignani |

Director | Olivier Py |

Sets | Pierre-André Weitz |

Lighting | Bertrand Killy |

Costumes | Pierre-André Weitz |

Text | Arrigo Boito |

Chorus Master | Martino Faggiani |

| ... | |

Video

The story

Act I: The Lion’s Jaws

In the courtyard of the Doge's Palace in Venice, the people celebrate the annual regatta. Barnaba, a spy and former informant of the Inquisition, watches over the festivities. He is filled with desire when he sees the beautiful singer La Gioconda guiding her blind mother, La Cieca, across the courtyard. La Gioconda leaves her mother to go in search of her beloved Enzo in the crowd, and Barnaba chases after her. When he is sharply rejected by her, Barnaba imagines getting revenge by attacking La Gioconda’s failing mother.

The people jubilantly welcome the winner of the regatta. One of the losers, Zuàne, has difficulty accepting his defeat. Barnaba whispers that he owes his defeat to a sinister spell cast by La Cieca. Hearing these words, Zuàne's supporters shout that La Cieca is a witch and that she should be executed. As Barnaba is about to have her arrested, Enzo tries to defend her. The young man is in conflict with the people who demand loud and clear that the old woman be lynched.

Alvise Badoero, one of the Inquisition's leaders, and his masked wife, Laura Adorno, come to see the cause of the disturbance. Barnaba urges them to sentence La Cieca, but Laura, moved by La Gioconda's pleas, manages to convince her husband to acquit her. In gratitude, La Cieca offers her rosary to Laura.

Barnaba makes Enzo understand that he holds him at his mercy: the spy knows that the young man is the outcast Enzo Grimaldo who has returned to Venice in secret, and that his relationship with La Gioconda is only to disguise his true love for Laura.

Once Enzo has gone to prepare for his rendez-vous with Laura that night, Barnaba dictates an anonymous letter to Alvise telling him of Laura's plan to escape with the outcast. Barnaba places the letter in the jaws of a post box shaped like a lion in which Venetians can slip their anonymous denunciations of offenders against the law. La Gioconda, who has left the church, listens unnoticed and witnesses Barnaba's revelation of Enzo's true love. Her heart is broken, while Barnaba is happy: as a spy, he considers himself more powerful than the doge.

Act II: The Rosary

Enzo waits aboard his boat while the crew prepares for departure. Just as the outcast believes Laura must no longer be coming as planned, she is led to the boat by Barnaba. The lovers embrace each other and dream of their new life together.

La Gioconda comes out from her hiding place on the boat and is unable to repress her jealousy and hatred towards Laura. The singer thinks of stabbing her but, seeing Alvise approaching on another boat, decides to let Laura face her husband’s revenge instead. In despair, La Gioconda grabs her rival’s rosary. She recognises it as La Cieca's and realises that Laura is the one who saved her mother from death. To repay the debt, the singer lets Laura escape by making her own boat available to her.

Enzo notices Laura's disappearance and finds himself facing La Gioconda. She points out to him the Venetian galleys that are surrounding his boat. In desperation, the outcast sets fire to his boat and swims away.

Act III: The Golden House

While a ball gets under way in the Ca' d'Oro, one of the richest palaces along the Grand Canal of Venice, Alvise plots revenge against his wife. He decides to make her drink poison, effectively forcing her to commit suicide and so condemning herself to hell. He shows Laura a catafalque that waits to receive her and he hands her a vial of poison to drink before the end of the ball.

La Gioconda has found her way into the palace and finds Laura alone just as she is about to ingest the poison. The singer exchanges her rival’s deadly beverage with a powerful drug that will plunge the young woman into a deep sleep that gives the illusion of death.

Checking up on his wife, Alvise finds Laura's body on the catafalque next to the empty vial. Satisfied to have been avenged, he welcomes his guests to the to ball, among them Enzo in disguise and Barnaba. Lavish entertainment is provided, including a sumptuous ballet, The Dance of the Hours. The mood of revelry is shattered as a funeral bell begins to toll and Laura still body is revealed. A distraught Enzo throws off his disguise and is promptly seized by Alvise's men.

Act IV: The Orfano Canal

Still asleep, Laura is secretly brought into La Gioconda's house by two men. She asks them to go in search of her mother, whom she had not seen since her arrest by Barnaba. The singer is torn between on the one hand her decision to reunite Laura and Enzo and then commit suicide, and on the other hand the temptation to return to Enzo and leave Laura to fend for herself. La Gioconda’s thoughts are interrupted by the cry of a gondolier who claims to have found a body in the Orfano Canal, and by the arrival of Enzo, whom Barnaba had liberated.

La Gioconda admits to her former lover that she had Laura's body collected. Enzo becomes violent towards the singer for letting him believe that Laura was dead. Just as he is about to kill her, Laura wakes up and reveals to Enzo that is was her rival who saved her from her husband. La Gioconda has also organised the couple’s escape from her house: a boat arrives to pick up Laura and Enzo and take them to safety.

Left on her own, La Gioconda fearfully waits for Barnaba to come and take his ‘payment’ for freeing Enzo. In a panic, she tries to escape but is caught by the spy. La Gioconda promises to give him her body as agreed and, drawing a dagger, she stabs herself to death. In his rage, Barnaba has the last laugh: he shouts to the dying women that last night he drowned her mother.

Insights

Europe burns its vessels

Olivier Py, director of La Gioconda, finds evil and decay in Hugo's play and Ponchielli's operatic adaptation.

As La Gioconda relocates Victor Hugo’s play Angelo, tyran de Padoue from Padua to Venice, it deprives the plot of its political dimension. For Hugo, his play is an indictment against all abuses of power. Just as the fate of women is the first sign of tyranny for Aeschylus, Hugo believes in democratic and feminist progress where women weave the future in solidarity.

Gioconda and Laura are therefore the alpha and omega of an impossible claim to freedom and equality. Maybe because he was born in Padua, the librettist Arrigo Boito transposes Hugo's piece to the city of the Doges; it could not only have been for decorative reasons. In Padua, the frightening shadow of Venice heralds the worst; in Venice, religious and political violence is so intertwined with everything that the city cries in spiritual despair.

The beauty of Venice is death; the greatness of Venice is decadence; the power of Venice is evil. In romantic terms, that is how the dark city fascinates and invites us to meditate on evil. The sleight of hand from one city to another is coupled with a change of narrator. Angelo, a bloodthirsty tyrant fixated on pursuing jouissance, becomes Barnaba, an amplified rewriting of Homodei's character. While Homodei is only a cog in the original drama, Barnaba is the drama of the opera. Disfigured by his addiction to pleasure, sucked into a maelstrom of envy and revenge, he is the Shakespearean figure of evil incarnate. Boito was no fan of anti-Manichaeism: in one of his short stories, L’alfier nero, a fight between a black and a white chess player leaves no room for nuance or ambiguous symbolism.

Barnaba, in a kind of Dantean description of the Venice of the Inquisition, crowns himself, a spy king above all things, a necessary radical evil in times of metaphysical questions. Boito transforms the political plot of Hugo’s play into a metaphysical poem, in which the ‘terrible singer’, as La Gioconda calls Barnaba, is a spiritual argument.

The play tells the story of Barnaba's relentless corruption of all moral values, of which La Gioconda is an impotent counterweight. For the spy, violating La Gioconda and taking her into her bed of despair is not only the most priceless enjoyment but the fulfillment of her lesson in darkness. It is because La Gioconda is beautiful and fair that she must be destroyed. There is nothing but death in the canals of Venice, and the sky is definitively extinguished.

Not only is Barnaba so drunk with power and influence that he has psychologically destroyed his mentor, Alvise, but he to rule in a world of such darkness as to cancel out God - this God whom the blind man sees, whom La Gioconda calls, whom Laura respects, whom Enzo fears and whom Alvise is familiar with in his power. This God, a true skeleton like the Doge of Venice, is now nothing more than a theatre accessory lost in the collapse of the most beautiful city in the world. The Venice of Tintoretto is a city between sky and sea, which longs to prove the existence of God through its beauty. It is a horizontal cathedral. Barnaba wants to debase its beauty just as he wants to degrade La Gioconda's, who is a metaphor for the people. A great negator weaves his web, leading each character to sacrifice and murder in a deadly desire that ultimately ends in necrophilia.

The opera curtain falls on an unimaginably sadistic scene, a retinal deflagration of evil, where the body of the inert heroine lies in front of the evil victor’s desire. We can wonder about this need for degradation and darkness that in Boito's work calls for music without harmonic resolution. It is the end of an era; the Verdian drama, with its foolish hope for democracy, its confidence in the integrity of the street, its faith in history, is no longer of concern in a twilighting Europe.

From this, Boito exalts a perfume of nocturnal celebration and decomposition. There is probably no other work in the whole operatic repertoire that is more absolutely black; La Gioconda’s sacrifice and La Cieca’s sanctity are present only to be debased. The evil is not only a block of abyss abandoned in the guilty garden of our history, but a devouring machine that produces its own clean fuel. It originates in the very need for music.

That's when Amilcare Ponchielli dared the unimaginable, and that may be the key to the uniqueness of the work. His music is neither pre-verismo nor post-Verdian, it is without parallel, an attempt to rise to the level of an unsustainable libretto. Abjection needs a mask to conceal itself in order to then unmask the ultimate truth. ‘The Dance of the Hours’ is therefore less a daydream about the obsolescence of things and more a story of fear that points towards the annihilation of humanism.

What if everything is getting worse and worse because of man’s desire to be crowned above the mysteries of the Being? When did this changeover take place? Just yesterday, we believed in the spring of peoples, in a future that sings, in a society, in the triumph of human rights; in one decade, the historical perspective has been reversed so that we no longer believe in anything but the worst.

Ponchielli and Boito have written a kind of last opera of the 19th century, a monument comparable to the one that Barnaba celebrates in ‘La bocca dei leoni’. The whistleblower becomes the ultimate prophet, the lion's mouth devours every transcendental hope. And all this horror becomes neither laughable, nor Grand-Guignolesque, nor complacent, nor easy; on the contrary, it remains, shimmering, dynamic, musical, incandescent. It's a fact: with La Gioconda, you can to say that the Europe of the Enlightenment has burned its vessels. It was only the feeling of the beginning of the end…

Olivier Py studied theater arts and techniques in Lyon before joining the Conservatoire national supérieur d’Art dramatique de Paris, while taking an interest in theology. He founded his own company in 1988, the year of his first play, Des Oranges et des ongles. In 1995, he created a buzz at the Festival d'Avignon with his show La Servante. In 1997, he became director of the Centre dramatique national d’Orléans, which he left in 2007 to direct the Odéon-Théâtre de l'Europe. Since 2013, he has been director of the Festival d'Avignon.

A committed artist, he stages many political pieces, or personal texts. For the past ten years, he has also devoted himself to staging opera, notably working at the Grand Théâtre de Genève, l’Opéra de Lyon, l’Opéra national de Paris, l’Opéra national du Rhin and La Monnaie.

Gallery