Orpheus and Eurydice

Cupid announces to Orpheus that he can bring back Eurydice from the Underworld. His song has the power to appease the Furies, but cannot soothe Eurydice, who despairs of Orpheus' feigned indifference, thus put to the test by Jupiter.

Orpheus and Eurydice shook up Enlightenment Europe. An adorer of Gluck, Berlioz synthesized the original Italian and French versions for Pauline Viardot, whose voice could revive the vanished art of the castrati for the Romantic public. Aurélien Bory's staging deploys the vertigo of the spaces through which Orpheus travels, mental, supernatural and beyond.

Cast

Orpheus | Marianne Crebassa |

|---|---|

Eurydice | Hélène Guilmette |

Cupid | Lea Desandre |

Dancers / Circus artists | Claire Carpentier, Elodie Chan, Yannis François, Tommy Entresangle, Margherita Mischitelli, Charlotte Siepiora |

Chorus | Pygmalion |

Orchestra | Pygmalion |

| ... | |

Music | Christoph Willibald Gluck |

|---|---|

Conductor | Raphaël Pichon |

Director | Aurélien Bory |

Sets | Aurélien Bory, Pierre Dequivre |

Lighting | Arno Veyrat |

Costumes | Manuela Agnesini |

Assistant Costumes | Claire Schwartz |

Assistant Directors | Hugues Cohen, Gabrielle Maris Victorin |

| ... | |

Video

The story

Act I

Nymphs and shepherds mourn over Eurydice's grave, while her husband repeatedly wails out her name. He invokes his lost love, curses the gods and contemplates seeking her in the Underworld.

Messenger of the gods, Cupid appears to announce to Orpheus that he may go to the Underworld, at the condition of two trials. He will have to coax the infernal creatures with his musical art and then, on the way back, refrain from looking at Eurydice, as well as from giving her any explanation. Hope rekindles Orpheus' courage.

Act II

The frightening entrance to the Underworld is guarded by spectres and furies who block its passage. But Orpheus gradually soothes them with the song of his complaint, his prayer, and the touching expression of his love. He enters the Underworld.

Act III

In the Elysian Fields that welcome the heroines and dead heroes reigns a bliss that seems to fulfill Eurydice. Moved by the harmony of the place, Orpheus cannot however forget his pain and calls Eurydice to the shadows. She is brought to him and he grabs her hand.

Act IV

Orpheus and Eurydice advance in the labyrinth that leads out of the Underworld. Surprised to return to life, Eurydice is quickly struck by the aloof attitude of Orpheus who has let go of her hand. She begs him in vain for a look, then refuses to follow him any further and soon faints with pain. Filled with remorse, Orpheus turns towards her. Eurydice dies a second time.

Insights

5 things to know about Orpheus and Eurydice

1° A universal myth

The myth of Orpheus has remained fascinating through time by virtue of its universal subject matter: the loss of a loved one and powerlessness in the face of death. It also symbolizes the incredible power of music and poetry. Orpheus is a virtuoso musician whose force of song makes everything and everyone - dead or alive - succumb. He represents the very allegory of music, and by the same token, of opera.

If the story of Orpheus is full of adventures and protagonists, his adventure truly begins when he falls in love with Eurydice and when she dies from a snake bite. Devastated, Orpheus looks for her in the Underworld with Cupid's help. Orpheus must not glance at her until they arrive on Earth's surface, otherwise he will cause her death a second time. Of course, Orpheus turns around, otherwise the myth would not exist.

Why did Orpheus fail to resist the temptation to turn around when he had succeeded in the hardest part: convincing Hades to let him enter the Underworld alive? Each author has his or her own interpretation. Does Eurydice stumble? Does she doubt Orpheus' love and force him to turn around? Does Orpheus want to make sure that Eurydice is following him? Is it simply his fate? The chosen explanation always provides a new perspective on the work.

2° An opera revised by Berlioz

When Berlioz, a true admirer of Gluck, was asked to adapt Orphée et Eurydice for the great Pauline Viardot in 1859, he decided to take his inspiration from the two versions established by Gluck: one Italian (role of Orfeo played by a castra) and the other French (role of Orphée played by a tenor). Berlioz kept the French score, but returned to the Italian version and transposed the tenor voice into a range suitable for Pauline Viardot. Orphée thus becomes a travesti role played by a mezzo-soprano. Berlioz harmonized the tonalities, especially for more modern instruments. The overture, considered too festive and mundane, was kept but played while the spectators settled down in the auditorium. The ending was shortened and modified.

It is thus an open work, reworked and reinterpreted at all times by numerous singers and composers, starting with Gluck himself, which the conductor Raphaël Pichon and the director Aurélien Bory appropriated in their turn. They chose not to play the overture from Berlioz's version (in French and with three female roles), which they considered too flamboyant and disconnected from the tragedy to come. They replaced it with another, more dramatic play by Gluck, Larghetto, taken from the ballet Don Juan or Gluck's Feast of Stone (1761). Likewise, the long dance scenes, imposed for the Paris Opera Ballet at the end of the work, are not all preserved.

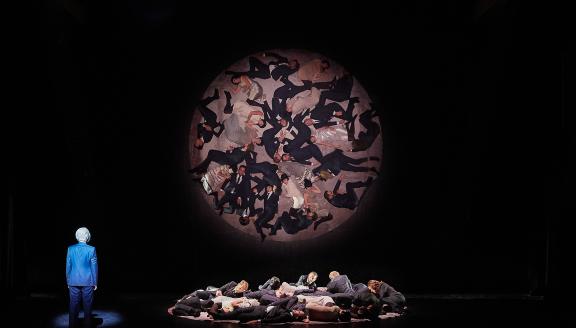

3° Pepper's Ghost Magic

Aurélien Bory defines himself as a director of space: he approaches the physical laws of the set and plays with gravity and perspective. Visually, he has chosen to use a universe and processes contemporary to Berlioz, as if to plunge the spectator back into the 19th century. It is thus thanks to a physical and optical device invented at the time that Aurélien Bory depicts Orpheus' ‘passage’ between the worlds of the living and the dead: the Pepper's Ghost, named after its creator.

This method of optical illusion allows objects - or individuals - to appear and disappear through the play of light reflection or transparency, using a thin sheet of glass (today replaced by light plastic) and special lighting. A high-definition projector, located above the stage, emits an image onto a transparent surface. The image is then reflected on a transparent screen, usually tilted at 45°, giving an impression of depth.

4° Painting invites itself on stage

The Pepper's Ghost is not only on stage to separate the world of the dead from that of the living, but also to showcase a great painting by Jean-Baptiste Corot, Orpheus Leading Eurydice from the Underworld. The reflection of the Pepper's Ghost makes Corot's painting appear as if it were hanging on hangers, on display to the spectators. For Bory, this work painted in 1862 naturally echoes Orpheus and Eurydice in Berlioz's version, which was created at the same time and presented at the Théâtre-Lyrique only three years earlier.

This coincidence also goes hand in hand with the spirit of transition, of passage, from the world of the dead to that of the living for Orpheus, from the change from a static to a moving opera that Gluck brought about, and in Corot's painting with perceptible strokes from the beginnings of the transition to Impressionism. Through images and acoustics, this production thus speaks of this principle of transition, separation and the consequences of choices made in a life.

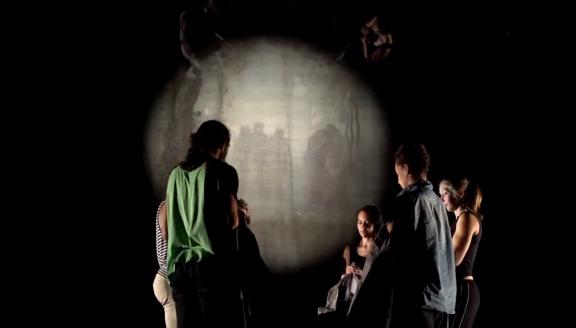

5° An opera that blends genres: from circus to magic

For Aurélien Bory’s theatre company compagnie 111, space counts above all else: ‘The stage is a space. (...) This space is the only medium of art where one cannot escape the laws of general mechanics. (...) Bodies, objects are subjected to gravity without any possible escape. (...) The body, the object are relevant to talk about gravity’.

The arts of dance, magic and circus allow the director to deal with space and gravity. Aurélien Bory has notably worked with Raphaël Navarro, a specialist in Magie Nouvelle (new magic), who places the imbalance of the senses and the diversion of reality at the centre of his artistic concerns. He was also inspired by Pina Bausch's ballet Orphée et Eurydice. Thus, circus performers and dancers, mixed with the Pygmalion choir, will play the Furies of the Underworld, dissuading Orpheus from entering it.

Gallery