Attila

In his attempt to conquer the world, Attila the Hun destroys all that lies in his path. Nothing seems to be able to halt his advance until a young female captive swears to avenge her father's death.

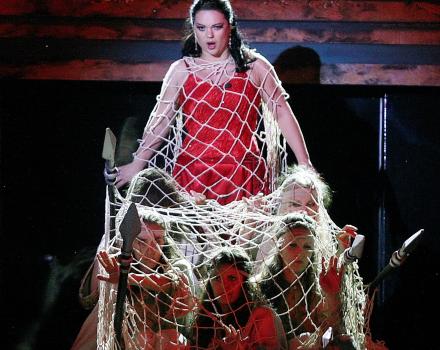

It is hard to imagine a more fitting setting for Verdi's incendiary drama Attila than Sofia Opera and Ballet’s production staged in front of the historic fortress of Tsarevets, one of the best loved monuments in Bulgaria. The composer’s contribution to the emerging Italian patriotism with the story of the fall of Attila the Hun was greeted with enthusiasm by his contemporaries.

Cast

Attila | Orlin Anastasov |

|---|---|

Ezio | Ventselav Anastasov |

Odabella | Radostina Nikolaeva |

Foresto | Daniel Damvanov |

Uldino | Plamen Papazikov |

Leone | Dimitar Stanchev |

Chorus | Chorus of Sofia Opera and Ballet |

Orchestra | Orchestra of Sofia Opera and Ballet |

| ... | |

Music | Giuseppe Verdi |

|---|---|

Conductor | Alessandro Sangiorgi |

Director | Plamen Kartaloff |

Sets | Plamen Kartaloff, Boris Stoynov |

Costumes | Lyubomir Yordanov, Pavlina Kotseva |

Text | Temistocle Solera |

Chorus Master | Violeta Dimitrova |

Concertmaster | Irina Stoyanova |

Stage manager | Vera Beleva, Rositsa Kostova |

Répétiteur | Yolanta Smolyanova |

| ... | |

Video

The story

Attila, the ‘scourge of God’, has invaded Italy and, on his way to besiege Rome, has destroyed the city of Aquileia.

PROLOGUE

Scene 1

The devastated city of Aquileia

Attila’s victorious army is celebrating the destruction of Aquileia. Against Attila’s orders, Uldino has saved a group of Italian women who took part in the fighting. Odabella, their leader, so impresses Attila that he offers to grant her a favour: when she asks for a sword, he gives her his own. Odabella vows to use it to avenge the death of her father.

The women leave and Attila sends for the envoy from Rome. It is Ezio, a Roman whom he has known in battle but whom he respects. Ezio asks for a private audience, and reveals that he is alienated by the current decadence of the Roman Empire. The Emperor of the East he says is old and frail and the ruler of the Western Empire is a mere boy. He proposes a bargain. ‘You will have the universe, leave Italy to me’. Attila contemptuously rejects the offer and accuses Ezio of treachery. Attila will march on Rome and destroy it.

Scene 2

Mudflats on the Adriatic lagoon

As calm returns after a night of raging storms, the hermits thank the Lord. They see a fleet of boats approaching the lagoon, carrying refugees from Aquileia. They are led by Foresto, who is mourning the loss of Odabella, his betrothed. He urges the people to establish an encampment where they have landed and to build a fine city which ‘will rise like a phoenix from the lagoon’ – a city which is to become Venice.

ACT 1

Scene 1

Near Attila’s camp outside Rome

Odabella laments her father’s death in the fighting at Aquileia. Foresto arrives. He has disguised himself as a Hun and accuses her of betraying him and his country by associating with her father’s murderer. Odabella, in despair, reminds him of the biblical story of Judith, who saved Israel by decapitating Holofernes on their wedding night. Foresto is astonished at her plans for revenge and forgives her.

Scene 2

Attila’s tent

Attila is terrified by a nightmare in which a figure in white barred his entry to Rome, saying ‘To be the scourge of mankind is your only task; turn back! The road is closed. This city belongs to God’. Attila fights his superstitious fear of the dream by rallying his men to advance on Rome.

Before the gates of the city a distant hymn is heard. Christian children and women are approaching, led by Pope Leo, who utters the words Attila heard in his dream. Attila collapses in terror and prostrates himself before Leo.

ACT 2

Scene 1

Outside the city of Rome

Ezio reads a despatch from the Emperor Valentinian: a truce has been declared with the Huns and Ezio is ordered to return to Rome. He reflects bitterly on Rome’s decline from glory. A group of Attila’s men arrive and invite Ezio and his captains to a banquet. One of them stays behind. It is Foresto. He tells Ezio to put his troops on alert and to attack the Huns when he sees the signal of a flaming beacon. Ezio is ready to die for Rome.

Scene 2

Attila’s camp

The Huns are feasting in honour of Attila and the truce when their Roman guests enter. Druids tell Attila to beware of the Roman. He ignores them, ordering priestesses tossing and dance. Suddenly, a fierce gust of wind blows out the torches. It is taken by the superstitious Huns as a doom-laden omen. In the confusion, Foresto tells Odabella that Attila’s wine is poisoned, and Ezio renews his offer of a pact with Attila. The sky clears and festivities resume. As Attila proposes a toast, Odabella dashes the chalice from his lips and saves his life. Foresto admits it was he who poisoned the wine. Odabella asks Attila to spare Foresto in return for her having warned Attila of the danger. He agrees and declares that the following day he will make Odabella his bride. She urges Foresto to flee. He swears vengeance for what he sees as her treachery. Attila and Ezio renew their hostility.

ACT 3

Outside Attila’s camp

Foresto, waiting to hear when Odabella’s wedding will take place, contemplates her unbelievable behaviour. He is tormented at the thought of her betrayal. Ezio impatiently demands the signal for the Roman army to attack the Huns.

Odabella rushes in, distraught, fleeing from the bridal room. Seeing Foresto, she pleads for forgiveness: she has always loved him. Attila follows and accuses Odabella, Foresto and Ezio of treachery. The sound of the attacking army inspires Odabella to seize the opportunity to kill Attila.

Insights

The Territory of the Gods

Attila is an opera in which the unexpected happens.

A primitive and elemental world

History teaches us that Attila the Hun was a fearsome military leader, a ruthless and organised conqueror, the ‘scourge of God!’ Yet, in this opera, Attila is prey to wild dreams and victim of a priest in a white robe.

We have learned that Verdi was a patriot, who supported the cause of a united Italy. Yet, this opera’s Italians are bloodthirsty and treacherous. The native Italians are either terrorists or devious politicians. It is the savage who is noble. Or rather, it is Attila who is vulnerable to emotion, while his cool adversaries use intellect to destroy his threat. In this aim they are abetted by the elements, which combine to unsettle and then demolish the invader.

Attila inhabits a primitive world. Verdi and his librettist Solera are careful to evoke this antique world of simple values. Much is made of natural forces – the heavens, gods, the skies, elemental moments. The prologue’s second scene begins with a storm, yielding to a programmatic dawn unusual for Verdi. The movement from darkness to light is echoed by the movement from piano to forte, from major to minor, and the prolonged resolution of dissonant chords. After the purging fire of the sack of Aquilea come the watery lagoons of the Adriatic. Solera’s consciously poetic text speaks of earth and sky.

An opera of confrontation between individuals

One might expect Attila to be composed as a noisy Risorgimento opera, replete with patriotic choruses. On the contrary, the use of the chorus is strictly functional. Attila is an opera about confrontation between individuals. It is a story of four people. Its drama is conveyed in duets, trios, quartets. It does not echo Verdi’s patriotic operas like Nabucco and I Lombardi, but follows Ernani and prefigures Il trovatore.

The key relationship between Attila and Odabella is an attraction of opposites, but a sexual attraction nonetheless. Why else does Odabella keep postponing the murder of Attila? She has every reason to kill him: love of her country, of her father, of her betrothed Foresto. Yet she is fascinated by the invader. Odabella’s romanza at the beginning of Act 1, with its evocative prelude and beautiful cor anglais obbligato, is a poignant depiction of her tortured state. The image of her dead father gives way to that of her lost lover. She is haunted by ghosts. The subsequent reunion with Foresto is hardly reassuring. They have become uneasy lovers, undermined by suspicion and misunderstanding. Odabella’s assumption of the mantle of the biblical assassin Judith both shocks and inflames Foresto.

The atmosphere of mistrust derives from the secrecy necessary among resistance fighters. Odabella does not confide her plans even to her closest allies. This may appear cold-blooded, but it may be that her silence is cover for indecisiveness. Foresto’s generosity is likewise drained by his insecurity.

Ezio is a more calculating figure, but also lonely. Attila condemns him for offering to make a deal rather than standing firm and fighting. But Ezio also holds values and suppressed passions. They emerge in his scene at the start of Act 2, when he is alone at night, revealed against the background of the great city of seven hills. Ezio is in love with the idea of Rome. It burns in his heart, endowing him with a fearsome nobility.

There is something chilly about Ezio and his fellow conspirators. Their actions may be justified, but they remain unlovable. By contrast, Attila, for all his cruelty and autocratic manners, embodies a rough generosity of spirit that compels admiration. Unafraid in battle, he is yet shaken to his foundations by the vision of the old man who seizes him by the hair and smiles into his face. Attila is appointed scourge of mankind, but before Rome his path is barred. This is the territory of the gods.

Verdi’s inspired brevity

As always with Verdi, it is the confrontations which inspire him. The great central scene of Attila’s dream is a prime example, but it is also clear that he was inspired by the other characters. He wrote about his source, Werner’s play:

‘There are three stupendous characters – Attila, who refuses to be thwarted by fate – Hildegonde [Odabella], a proud and really fine character obsessed with the idea of avenging her father and brothers and lover – and Aetius [Ezio] is very fine too, and I like that bit of dialogue with Attila where he suggests they share out the world between them. We ought to bring in a fourth strong character and I think it should be Walther [Foresto] who believes that Hildegonde is dead, and has somehow escaped’.

Solera, the extravagant patriot, wished to end the opera with a great choralhymn of thanksgiving, but he was called away by other commitments, and Verdi reverted to Piave for the final scene of the opera. Piave’s completion has been criticised as perfunctory, but it has its own inexorable logic. After the grandiose scenes and images – the sacked city of Aquileia and the city of Venice rising from the lagoon; the Pope before Rome and the torchlit banquet – Act 3 benefits from a remarkable concentration and terseness. It moves from Foresto’s lonely despair to his duet with Ezio to the trio joined by Odabella to the concluding quartet of the principals. The whole act lasts little more than 15 minutes. The cynical will say that this is Verdi, ill and exhausted, clearing the decks before collapsing. If so, it is a bold and risky achievement so to expose his four characters to the mercy of the elements, naked before the gods.

Nicholas Payne

Gallery