Die Walküre

Siegmund and Sieglinde find themselves drawn together during a storm. Unbeknown to them their father is Wotan, chief of the gods, who through Siegmund hopes to retrieve a ring of ultimate power.

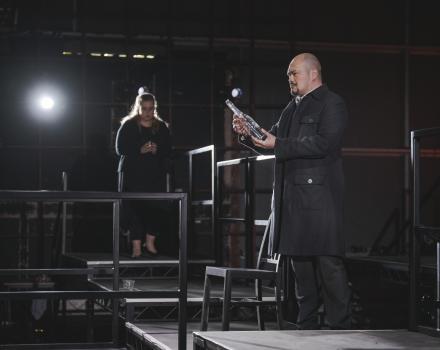

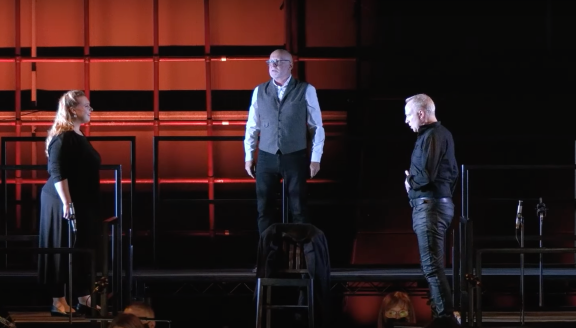

Following Longborough Festival Opera’s critically acclaimed Das Rheingold, Wagner’s epic tale of Der Ring des Nibelungen continues with Die Walküre, conducted by Longborough’s Music Director Anthony Negus, ‘who probably knows The Ring better than any other living British conductor’ (The Times) and semi-staged by Amy Lane. The predominantly British cast shows several generations of great Wagnerian singers at their best.

Cast

Siegmund | Peter Wedd |

|---|---|

Sieglinde | Sarah Marie Kramer |

Wotan | Paul Carey Jones |

Fricka | Madeleine Shaw |

Brünnhilde | Lee Bisset |

Hunding | Brindley Sherratt |

Gerhilde | Meeta Raval |

Ortlinde | Cara McHardy |

Waltraute | Flora McIntosh |

Schwertleite | Rhonda Browne |

Helmwige | Katie Lowe |

Siegrune | Carolyn Dobbin |

Grimgerde | Katie Stevenson |

Rossweisse | Emma Lewis |

Orchestra | Longborough Festival Orchestra |

| ... | |

Music | Richard Wagner |

|---|---|

Conductor | Anthony Negus |

Director | Amy Lane |

Lighting | Charlie Morgan Jones |

Assistant Conductor | Peter Selwyn |

Répétiteur | Kelvin Lim |

Language Coach | Dominik Dengler |

English subtitles | Sophie Rashbrook |

Casting | Malcolm Rivers in partnership with The Mastersingers |

Artistic Advisor | Isabel Murphy |

Reduced orchestration | Francis Griffin |

| ... | |

Video

The story

Act I

In a violent storm, a stranger takes refuge in the home of Sieglinde and Hunding. On Hunding’s return it becomes clear that the unarmed stranger is in flight from Hunding’s kinsmen. The law demands that Siegmund be offered hospitality for the night, but Hunding warns that revenge will follow in the morning. Sieglinde gives Hunding a sleeping draught and tells the stranger of the sword buried in the tree. As they share their stories, mutual feelings grow swiftly into a passionate expression of love. Sieglinde, drawing on her earliest memories, also realises that he is no stranger. He is her twin brother, and she names him – Siegmund. In the strength of this new identity, Siegmund draws the sword from the tree, and brother and sister escape as Bride and Bridegroom.

Act II

Wotan sees in Siegmund an opportunity to regain the ring of power that was lost during the events of Das Rheingold, held now in the clutches of the giant, Fafner. Wotan asks his favourite daughter, the Valkyrie Brünnhilde, to protect Siegmund in his coming fight with Hunding. Fricka, wife of Wotan and Goddess of Marriage, is outraged by Wotan’s infidelity and the incestuous behaviour of the twins. On Fricka’s demand, Wotan must order Brünnhilde to let Siegmund fall in the battle with Hunding. Wotan shares his history and darkest moments with Brünnhilde and then gives Fricka’s order to the Valkyrie: Siegmund must die in the battle. As Sieglinde and Siegmund flee from Hunding, Brünnhilde appears and ultimately offers her protection. Siegmund and Hunding fight, and Wotan shatters his son’s sword, causing Siegmund’s death. Brünnhilde carries Sieglinde and the splintered sword away, Wotan vowing revenge for her disobedience.

Act III

The Valkyries gather on the rocky mountain, before taking the dead heroes up to Wotan and Valhalla. Brünnhilde brings Sieglinde to them, begging for their support in the face of Wotan’s anger. She reveals that Sieglinde is carrying a child who will be called Siegfried, but they refuse to help her for fear of Wotan’s wrath. Brünnhilde gives Sieglinde the shattered pieces of the sword, Nothung, which one day Siegfried will forge again. She then sends Sieglinde off to the forest to fend for herself, remaining to receive Wotan’s judgement. Wotan arrives in a huge storm, and as punishment for her disobedience strips Brünnhilde of her powers, removing her immortality. He places her into a deep sleep, for a mortal man to come and claim her as Wife. On Brünnhilde’s insistence, Wotan surrounds the rock on which she sleeps with fire: only a fearless hero worthy of her will be able to brave the flames.

Insights

A Tale of Two Heroes

Sophie Rashbrook interviews Longborough’s Music Director and Die Walküre conductor Anthony Negus.

Die Walküre. The Valkyrie. If we ponder, for a moment, over the title Wagner gave to the second instalment of his Ring Cycle, one could be forgiven for expecting it solely to revolve around its eponymous heroine. However, as Longborough Music Director Anthony Negus explains, there is far more to the opera than just the story of Wotan’s Valkyrie daughter: ‘It really is two stories rolled into one. If you were to take just the first two Acts, you could call it “The Life and Death of Siegmund”. It’s only in Acts Two and Three that her story overlaps with that of the twins, Siegmund and Sieglinde, and Brünnhilde emerges as the heroine.’

It is the overlapping of these two characters’ destinies that provides the crucial turning point of the drama: moved by the twins’ love for one another, Brünnhilde defies her father’s orders, with far-reaching consequences for the whole Cycle. For Anthony, there is a practical aspect to understanding Die Walküre as a tale of two protagonists: ‘As an interpreter, I’m helped by thinking of the arcs of those two characters, Siegmund and Brünnhilde. It gives unity to the opera, and in particular, to the huge, and some might say, slightly sprawling, second act.’

It is now eight years since Anthony’s last experience of conducting the complete Ring Cycle at Longborough, and he is fascinated by the ways in which his approach has evolved in the interim. ‘I think I’ve found greater precision, and I’ve also taken some inspiration from listening to recordings conducted by Wilhelm Furtwängler. His sense of pacing was extraordinary, and he really gives a sense of the constant development of the music as it unfolds.’ Disregarding, for a moment, the four hours of Die Walküre, is pacing a challenge, I ask Anthony, when preparing for the 2024 Longborough season? Many Longborough audience members will be aware that this is when Anthony is scheduled to conduct the tetralogy in its entirety, yet he is unphased: ‘It’s really a Trilogy with a Prelude. The Prelude – or Vorabend, as Wagner calls it – is Das Rheingold, but what a prelude. I’m just quite sad we have to wait for three more years before we get to hear all four operas together!’

In Wagner’s lifetime, audiences had to wait considerably longer to hear the complete Cycle in sequence. Wagner composed the texts for each opera in reverse order, subsequently setting them to music in chronological order between 1853 (Das Rheingold) and 1874 (Götterdämmerung); a period which included a hiatus of 12 years, during which he composed Tristan und Isolde and Die Meistersinger. It wasn’t until 1876 that the four operas premiered as a complete Cycle at the Bayreuth Festival; Wagner’s own, iconic, purpose-built theatre from which Longborough takes its inspiration.

Anthony’s knowledge of Wagner’s operas gives him a unique perspective on the pivotal role of Die Walküre within the context of the whole saga: ‘It sets in motion the events of the rest of the series. Siegmund is supposed to be Wotan’s free and independent hero; but as Fricka points out, Wotan himself has fatally sabotaged this plan by placing the sword in the tree, thus helping him to find it. We also see the development of Wotan, from quite a crude character in the Rheingold, to someone who is imbued with tragic depth. And we see Brünnhilde’s courage, when her father, Wotan, threatens to punish her, by placing her into an enchanted sleep. She has the inspiration for the ring of fire, from which she can only be rescued by “the one without fear” – and the music tells us who that is!’ Before we get to Siegfried, however, we must wait another year.

Meanwhile, Anthony is enthusiastic about the distinctive musical qualities. ‘Although the opera refers back to Das Rheingold, with each successive opera, the music takes over more and more, and in Die Walküre, there are long passages of continuous music without singing.’ He cites a crucial example of this in Act I, where Sieglinde attempts, by the power of her gaze alone, to make Siegmund aware of the sword in the tree: ‘Because her husband, Hunding, is there, she cannot speak to Siegmund directly, and so the orchestra plays what she cannot express in words.’ Die Walküre also plumbs new depths of expression in its depiction of the growing empathy between the siblings: ‘Act I of Die Walküre is many people’s favourite. It shows the blossoming of their love, and you feel such deep compassion for their fate.’

Last, but not least, according to Anthony, the opera contains nothing less than ‘the most glorious melody in the whole Ring’: the moment where Sieglinde learns from Brünnhilde that she is carrying Siegmund’s child, and she sings the words: ‘O hehrstes Wunder! Herrlichste Maid!’ (‘Oh glorious miracle, most wonderful maid’). ‘That melody is sometimes referred to as “The Glorification of Brünnhilde”. It only comes back in Götterdämmerung [the final instalment], when it is a symbol of redemption, and Walhalla, the palace of the Gods has been destroyed. But no one sings the theme with such a wonderful line as Sieglinde in that moment.’

It seems rather daunting to imagine that a single musical phrase can encapsulate and foreshadow the apotheosis of the entire Ring Cycle. With such vast swathes of narrative to traverse, and so much music to perform, I ask Anthony what goes through his mind in the seconds before the opera begins? ‘That’s a very good question.’ He pauses, contemplating the scene. ‘The music has got to come alive, viscerally, in the moment. I think my immediate thought is: if I can get it right at the beginning, it will all come together. It’s a leap of faith.’ A leap of faith which we will all take together, alongside the heroes of Die Walküre.

The interview was conducted by writer, librettist, and opera dramaturg Sophie Rashbrook.

Gallery