Nothing is what it seems in an old English manor. When a new governess arrives, the children entrusted to her care seem to receive visits from the ghosts. What horrors occurred here before her arrival? Are the children innocent? Can we really trust what we see?

Based on a ghost story by Henry James, Benjamin Britten’s The Turn of the Screw is a psychological thriller in chamber opera format. The work’s layered and emotionally charged nature is an ideal fit for the director Andrea Breth. Together with the British conductor Ben Glassberg, she turns the screw of your imagination until the tension becomes unbearable.

Cast

The Prologue | Ed Lyon |

|---|---|

The Governess | Sally Matthews |

Miles | Henri de Beauffort |

Flora | Katharina Bierweiler |

Mrs Grose | Carole Wilson |

Peter Quint | Julian Hubbard |

Miss Jessel | Giselle Allen |

Orchestra | Kamerorkest van de Munt / Orchestre de chambre de la Monnaie |

| ... | |

Music | Benjamin Britten |

|---|---|

Conductor | Ben Glassberg |

Director | Andrea Breth |

Sets | Raimund Orfeo Voigt |

Lighting | Alexander Koppelmann |

Costumes | Carla Teti |

Text | Myfanwy Piper after the story by Henry James |

Artistic collaboration | Eva Di Domenico |

Sound design | Christoph Mateka |

Konzertmeister | Saténik Khourdoïan |

Film director | Myriam Hoyer |

| ... | |

Video

The story

Act One

Prologue

The Prologue tells a strange story, written in faded ink: a governess’ first position is at a country house called Bly, looking after two children Miles and Flora, who are reaching puberty. However, there is one stipulation: the governess is not to bother their guardian either verbally or in writing about any matters relating to the children. The Governess accepts the challenge.

Scene one – The Journey

The Governess sets off apprehensively. How will the children receive her? She has left behind everything she knows; she has no one to ask for advice and will have to make all her own decisions.

Scene two – The Welcome

Miles and Flora excitedly await the arrival of the Governess and ask endless questions about her of the housekeeper, Mrs Grose. When the Governess eventually arrives, the children greet her with a practised bow and reverence. The talkative Mrs Grose is keen to tell the Governess about the children, while the two children cannot wait to show the newcomer around her new work environment.

Scene three – The Letter

An official letter arrives saying that Miles has been expelled from school. The Governess and the housekeeper cannot imagine that Miles has misbehaved. While the children sing a seemingly innocent song, the Governess decides not to react to the letter.

Scene four – The Tower

All alone, the Governess enjoys the beauty of the surroundings, until she suddenly spots a stranger on one of the towers. She is afraid because she can’t imagine who he could be.

Scene five – The Window

Again the children entertain themselves with a song, though it sounds more aggressive than the last. The Governess has seen the stranger for the second time. According to Mrs. Grose, it can only be Peter Quint, the former manservant who died. She says he not only took liberties with the children but also with the Governess’ predecessor, Miss Jessel. But Miss Jessel is dead too.

It would seem that the unpleasant events of the past are not entirely over and the Governess becomes increasingly aware that she is going to have to keep a very careful watch over the children.

Scene six – The Lesson

In the classroom, Miles shows how many Latin phrases he knows, while his sister prefers to study history. He surprises the Governess with a mystifying song.

Scene seven – The Lake

Flora recites the names of the seas while playing with her doll at the lakeside. The Dead Sea fills her with fear. Suddenly the Governess asks Flora to help her look for her brother. Miss Jessel appeared to her and she fears that both children will be lost if they come under the influence of the former employees.

Scene eight – The Night

Peter Quint seems to want to keep a hold on Miles, while Miss Jessel directs her hidden powers at Flora. With mysterious myths and dream-like events, they try to exercise power over the children. The Governess is desperate to free them from the clutches of the dead but she needs Mrs Grose’s help.

Act Two

Scene one – Colloquy and soliloquy

Back in their former violent relationship, Peter Quint and Miss Jessel argue about their influence over the two children. However, one thing is certain: the age of innocence is over. In her solitude, the Governess realizes this too.

Scene two – The Bells

The children sing a hymn in honour of the dead, but there seems to be more to their song than meets the eye. While Mrs Grose praises the beauty of the day, the Governess no longer believes in the children’s innocence. She is convinced that the dead employees have them in their power. Mrs Grose believes that only a letter to their guardian can help, but the agreement was to leave him in peace. While Miles asks if he can spend time with his peers again, the Governess considers fleeing the place she now finds so terrible.

Scene three – Miss Jessel

When the Governess comes into the classroom, she finds Miss Jessel sitting in her seat. She is not prepared to be pushed out and calls her predecessor to order. In these circumstances, she cannot leave Bly. A letter to the guardian does seem to be the only way out.

Scene four – The Bedroom

Miles, who hasn’t gone to bed yet, sings his sad song again. The life they are all leading gives him cause for concern. The Governess takes him into her confidence about the letter she has written to the guardian, not least because she still doesn’t know why he was expelled from school. While she offers Miles her help, Peter Quint’s influence over him seems to be increasing.

Scene five – Quint

Miles has intercepted the letter - probably at Quint’s behest.

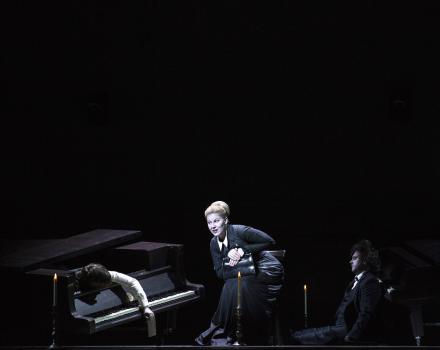

Scene six – The Piano

Miles impresses the Governess and Mrs Grose with his masterly piano playing. Flora seizes the opportunity to slip away. As Miles is already in Quint’s power, the Governess decides it is better to leave him in peace and concentrate on looking for Flora.

Scene seven – Flora

The two women find Flora. For the Governess, there is no doubt whatsoever that she followed Miss Jessel, while Mrs Grose sees no trace of Miss Jessel. An argument with the Governess ensues. Flora takes advantage of the quarrel to reproach the Governess and escape her care. The Governess is forced to recognize that she has failed.

Scene eight – Miles

Mrs Grose feels duty-bound to leave with Flora. The guardian, however, is not aware of events at Bly, because Miles has intercepted the letter. The Governess still believes she must protect Miles from the ghostly goings-on and save him. While Quint seems to be urging Miles to remain silent, the Governess insists that he tells her the truth. Naming Quint could mean his liberation. She achieves her objective, but Miles dies in her arms after uttering Quint’s name.

This article by Klaus Bertisch is published with the kind permission of La Monnaie / De Munt.

Insights

Britten's Fascination for the Unspoken

Today, at the beginning of the 21st century, it is well known and widely accepted that the English composer Benjamin Britten (1913-1976) and the tenor Peter Pears (1910-1986) were in a relationship. At the time of the composition and first great success of Britten's ninth opera The Turn of the Screw, this fact was by no means self-evident and the love between the two artists had to blossom in secret. Perhaps the fact that Britten had to constantly suppress his emotions and feelings in public explains why he often turned to material in which the fascination spoke primarily from what was not said or shown.

In none of the three operas, Peter Grimes, Billy Budd or The Turn of the Screw, does one learn the real facts that led to disaster. Did the ghosts of the deceased servants Peter Quint and Miss Jessel in The Turn of the Screw really appear to the governess and exert a negative influence on the children entrusted to her care? We do not know. However, Benjamin Britten's works, once we know his personal predilections, are full of almost undisguised innuendo. In The Turn of the Screw, there are a multitude of at least ambiguous passages. The naïve 6th scene alone, 'The Lesson', with its numerous Latin expressions, contains a whole arsenal of seemingly harmless vocabulary that, on closer inspection, is full of phallic symbolism. In the same scene, Miles' mysterious and frequently recurring 'Malo' song is heard for the first time, which is in itself ambiguous. Malo could be interpreted as a quality (from the Latin malus - evil, bad), or it could be a harmless song about a tree: malum - the apple, apple tree). A fascinating song that is multi-layered and unexplainable, and should remain so.

The ambiguity of The Turn of the Screw

What matters most, then, is what is not said or shown in the plot. With Peter Quint and Miss Jessel, characters appear who have in fact already died. Are they ghosts, or are they real? For Andrea Breth, the director of The Turn of the Screw, they are first and foremost figures she has to stage, given that they make a concrete appearance on stage. It seems reasonable to think that Peter Quint and Miss Jessel have sprung from the governess's imagination. Even though they seem to speak independently, especially at the beginning of the second act, whereas with James they never speak, with the governess the unnamed protagonist is always present and the scene is possibly a product of her imagination.

It was a stroke of genius on Britten's part to ask his librettist Myfanwy Piper to have the ghosts appear as singing characters, to provide them with text that is not present in Henry James' original. He thus breaks away from the form of the original (a triple first-person narrative) and finds a dramatic design. However, it cannot be a coincidence that Britten assigns several of his characters to the same voice type at the same time, to complete the confusion. In many passages, the governess's vocal lines are interchangeable with those of Miss Jessel or even Flora, who is entrusted to her. Incidentally, this also applies to the roles of Peter Quint and those of the Prologue. Andrea Breth's production makes use of this several times. These are not corrections, but theatrical devices that correspond to the basic mood of the work and even heighten it. The Prologue and Peter Quint are often cast with the same singer in a wide variety of productions. (Britten had composed both roles for Peter Pears.) This was more of a practical solution, for a clear equation of the two characters in terms of content is inconceivable. They are completely different characters. It would be too clear if one could identify one with the other. The play with the same voice types, however, is heightened when one sometimes doesn't know or notice who is saying or singing what. The tension is heightened by the question of whether it is one or the other.

It is also interesting in this context that the prologue and the governess are characters without names. The prologue (a summary of two narrators in Henry James) sets the plot without intervening himself. Thus its being nameless also corresponds to its function and its neutrality in the context of the story. It seems to be different with the governess. The other characters are mirrored in her. She is nameless because her fate is universal. Her fate, her imagination, her fantasy applies to all the lonely, job-seeking, neglected women of the time. Her name is of no interest.

In the first scene of Act 2, librettist Myfanwy Piper quotes from a poem by W. H. Auden entitled ‘The Second Coming’. This poem evokes change and announces a negative turning point in time. It marks the end of youth, of innocent playfulness. But it also becomes clear that one cannot escape the forces of change. A new power is called upon to take over. The ceremony of innoncence is drowned! And it is Miles and Flora in particular who are certainly no longer as innocent as one would like children to be. The dear little ones are going through puberty and have their own games, their own opinions and their own will too. They do not fulfil the expectations imposed on them. And since the young and naive governess could never live out her own desires herself, substitute figures had to be found who embody the evil that one does not really want to see in children: Peter Quint and Miss Jessel as a kind of catalyst for the initiation to a new existence. W.H. Auden's poem with its images of abyss and nightmare is perhaps the only feature from which a thought of death could ignite.

The inestimable value of doubt

However, the opera and the novella are not so much about the corrupting influence that two deceased characters might have as ghosts on the children of an absent lord of the manor. They focus more on how the imagination of an individual can go so far as to influence reality or change it to such an extent that ultimately only a separation from the object is possible. The death of someone changes the situation in a single blow. In this sense, Britten's opera functions like an Alfred Hitchcock film, in which the tension is built up to infinity, only to finally reach a surprising and unexpected end. MiIes' sudden death catches the audience completely off guard. Ghosts are a product of the imagination that can have its effects on a character. But the main point is to stimulate that imagination and come up with surprises than to provide unambiguous interpretations that allow no room for one's own thinking, reading or listening.

Thus, a story unfolds that is much less based on or influenced by any kind of reality, and certainly does not evoke a Victorian age for today's audience, but rather a spectacle about youth and old age, life and death, permanence and new beginnings that fires the imagination. A play that raises more questions than it answers. When reading Henry James' novella, it seems perfectly normal that images arise in the reader's mind's eye that everyone can create for themselves or has to contemplate. But this should also be the case when attending this opera, namely that a prefabricated age does not provide clear-cut answers in order to then confront the audience with perhaps disturbing possibilities.

Andrea Breth's production, designed by Raimund Orfeo Voigt, offers unreal images. Rooms open up, offering the viewer configurations suggested by the work, but without exempting them from using their imagination. Sliding partitions reveal the expected and the unexpected, only to conceal them again, and thus counterbalance the disturbance caused by the narrative. Above all, this reflects Britten's assumption of the unspoken. In director Andrea Breth's hands, imagination and detailed reading are not contradictory. The spatial transformations follow the train of thought, reveal surprises and then reject them again. New ideas also bring hope for change. Thus, not knowing and not seeing, in the sense of the composer's system, may not only allude to the darker sides of human existence, but also, in the wake of such a lyrical experience, sharpen the awareness of an otherness in the face of the ordinary and the normative. We must beware of condemning what we do not know or know not. This piece also tells us that.

This article by Klaus Bertisch is published with the kind permission of La Monnaie / De Munt.

Gallery