Death in Venice

While a mysterious illness spreads in Venice, an ageing writer on holiday finds himself dangerously infatuated with a young boy. As his moral convictions give way to his increasing obsession, everything he holds true begins to tumble around him.

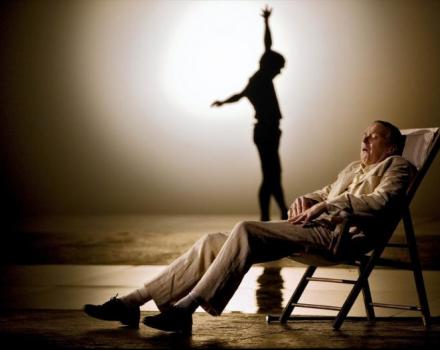

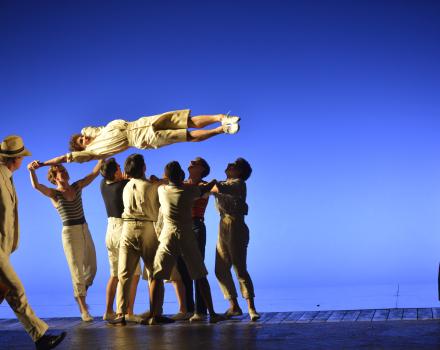

Composed while his own health was in decline, Britten's passionate adaptation of Thomas Mann's classic novella Death in Venice was to be his last opera.Its feverish urgency suggests that Britten was aware that it would become his musical testament. Deborah Warner's critically acclaimed staging elegantly combines unsettling music, evocative dance sequences and atmospheric sets.

Cast

Gustav von Aschenbach | John Graham Hall |

|---|---|

Traveller / Elderly Fop / Gondolier / Barber / Hotel Manger / Player / Dionysus | Andrew Shore |

Apollo | Tim Mead |

Tadzio | Sam Zaldivar |

The Polish Mother | Laura Caldow |

Two Daughters | Mia Angelina Mather / Xhuliana Shehu |

The Governess | Joyce Henderson |

Jaschiu | Marcio Teixeira |

Chorus | English National Opera Chorus |

Orchestra | English National Opera Orchestra |

| ... | |

Music | Benjamin Britten |

|---|---|

Conductor | Edward Gardner |

Director | Deborah Warner |

Text | Myfanwy Piper |

| ... | |

Video

The story

The action takes place in 1911.

Act I

The celebrated author Gustav von Aschenbach struggles with his incapacity to write. By the entrance to a cemetery in Munich, he encounters a Traveller and is filled with a longing for the sun and the south.

On the boat to Venice, Aschenbach is shocked by the behaviour and appearance of an Elderly Fop and some rowdy youths. Aschenbach is rowed by an Old Gondolier who insists, despite Aschenbach’s protests, on taking his passenger direct to the hotel on the Lido. On arrival at the hotel, the Old Gondolier disappears without waiting for payment. Aschenbach is greeted by the Hotel Manager and shown to his room. Watching the hotel guests assemble for dinner, Aschenbach catches his first sight of a Polish boy and his family. He is struck by the boy’s appearance and muses on the nature of beauty and its implications for the artist.

Aschenbach is anxious that the sultry weather might force him to leave. He buys some strawberries and observes a group of children playing on the beach. His first impressions of the Polish boy – Tadzio – are confirmed. Aschenbach crosses the lagoon to visit the city. Fearing the effect of the sirocco on his health and troubled by beggars and street vendors, he resolves to end his stay. He departs for the railway station but a mix-up with his baggage, which has been misdirected, sees him return to the hotel.

On the beach, Aschenbach watches Tadzio and his friends competing in a sequence of games. Aschenbach’s thoughts turn to Ancient Greece and, as the Voice of Apollo is heard and the children’s games become myths and the beach Socratic Greece, the writer’s muse is released. Tadzio is victorious in the games but Aschenbach is unable to congratulate him.

Act II

In the Hotel Barber’s shop, Aschenbach learns that there is a mysterious sickness in the city and that many guests are leaving. Aschenbach becomes obsessed with the desire, on the one hand, to know the truth about the sickness, and on the other to keep knowledge of it from Tadzio and his family. He follows them into St Mark’s, on a gondola ride and back to the hotel.

A group of strolling players entertains the hotel guests, including Aschenbach and Tadzio. Aschenbach asks the Leader of the Players directly if there is a plague in Venice. Aschenbach finally learns the truth from an English clerk: that Venice is in the grip of cholera, and that for fear of commercial loss the city authorities have tried to conceal it. The clerk advises Aschenbach to leave without delay. Aschenbach decides to warn Tadzio’s mother, but when he sees her he fails to speak. He recognizes that this last failure reveals the depths to which his obsession with Tadzio has brought him.

As he sleeps, Aschenbach dreams: the two sides of his personality – the Apolline (by which he has hitherto been ruled) and the Dionysiac – struggle for ascendancy. When Dionysus claims him, Aschenbach suddenly awakes and is resigned to his fate.

Watching from afar Tadzio and his friends playing on the beach, Aschenbach reiterates his decision to abandon himself to his passion. Aschenbach makes a second visit to the Hotel Barber, whom he allows to make him look younger.

Aschenbach continues his pursuit of Tadzio across the city. The boy sees him but does not betray him. Exhausted and confused, Aschenbach rests for a moment. He buys some strawberries, but they are musty and over-ripe. He recalls what he once learned about passion and beauty from reading Socrates.

All the guests are leaving the hotel, including the Polish family. Aschenbach goes to the beach to watch Tadzio for the last time.

Insights

Death in Venice: the interwoven lives of Britten and Mann

Mann’s ‘tragedy of humiliation’

Published in 1912, on the eve of the First World War, Nobel Prize-winning German writer Thomas Mann’s classic novella Death in Venice is the ultimate exploration of the dialectics of Apollonian rationality and Dyonisian passion that has shaped Western culture from Plato to Schelling and Nietzsche.

Suffering from writer’s block, the novella’s protagonist, renowned author Gustav von Aschenbach, visits Venice. There he gets increasingly entangled in his obsession with a beautiful young boy named Tadzio whom he never dares to approach. Later calling his work a ‘tragedy of humiliation’, it follows Aschenbach’s lapse from being a bulwark of morality to succumbing to emotional frenzy.

The novella is partly autobiographical: numerous incidents, including the momentous encounter with the young Polish baron Władysław (Adzio) Moes, stem from the Mann family’s trip to Venice in 1911. Even Aschenbach's literary works cited in the novella coincide with those already completed or planned by Thomas Mann.

It is as well that the world knows only a fine piece of work and not also its origins, the conditions under which it came into being; for knowledge of the sources of an artist’s inspiration would often confuse readers and shock them, and the excellence of the writing would be of no avail.

Unexpected connections...

Britten had long contemplated adapting Death in Venice into an opera, considering its author a central figure of modern European literature. If at first sight Mann and Britten seem to inhabit different artistic and personal worlds, there is, in fact, considerable overlap between their respective lives. Britten’s close friend, the poet W.H. Auden, married Mann’s eldest daughter Erika in 1935, the very summer they met. If the union was a marriage of convenience between two gay artists, which enabled the politically engaged cabaretist Erika Mann to escape the Nazi regime, they nonetheless never divorced and remained lifelong friends.

When Britten and his partner, the tenor Peter Pears, emigrated to the United States for a while in 1939 where they ended up living together with a group of émigré artists in Brooklyn Heights, among them: Auden, Erika Mann and her brothers Golo and Klaus, writers in their own right. While it is not documented whether Thomas Mann, who lived in Princeton, New Jersey at the time met Britten, though it seems likely given their mutual connections. At the time, Mann did not seem too impressed with Britten. In a 1948 letter he recalls that ‘Back then, the young musician seemed not to have given the impression of genius. I suppose it was the story of the ugly duckling.’

In 1970, Britten finally approached Golo Mann about turning the Death of Venice into an opera, receiving a heartwarming acknowledgement about his father’s appreciation of his music.

My old mother, and I, and everybody concerned, would be delighted, would be happy, would be enthused if you could realize this project. Need I point out and explain, why we would? My father, incidentally, used to say, that if it ever came to some musical illustration of his novel Doctor Faustus, you would be the composer to do it [. . .] a Death in Venice opera by BB would have made the author of Death in Venice happy.

At the same time, Golo Mann informed Britten that Luchino Visconti was working on a film adaptation. Visconti had decided to turn Aschenbach’s character into a composer, magnifying Mann’s allusions to Gustav Mahler through his name and appearance. As evocative as the film otherwise might be, this transposition distorts Mann’s reflection on Aschenbach’s conflict between Apollonian reason and Dionysian passion. Music, it can be argued, is intrinsically indebted to a Dionysian spirit.

From the page to the stage

Britten and his longtime librettist Myfanwy Pipe portray this inner conflict in a dream scene opposing the gods Apollo and Dionysus together in a contest in which Apollo is defeated, sealing the final disintegration of Aschenbach. All in all, Britten and Piper’s adaptation would prove much more faithful, treading a fine line of preserving Mann’s original framework and flavour while operating important changes to make it feasible on stage. They streamlined the plot by skipping the beginning of Aschenbach's holiday on the Adriatic coast.

In an inspired dramaturgical move, they blend four of the novella’s ominous characters symbolize death – the Traveller, the Elderly Fop, the Old Gondolier and the Leader of the Strolling Players – into a single baritone role. By also including Dionysos as well as the Hotel Manager and the Barber, who both involuntarily incite Aschenbach’s ruin, Piper and Britten fashioned a substantial role opposite Aschenbach in what would otherwise have resembled a monologue.

Piper’s intuition to cast the role of Tadzio as a non-verbal dancer proved a stroke of genius perfectly translating Mann’s intent. Offering Britten a complementary visual form of expression, Tadzio is lifted from his worldly status to impersonate the idea of beauty through movement.

I followed the performance with the greatest involvement and felt the opera to be the equal of the novel. The interpretation of Aschenbach by Peter Pears I thought was excellent [. . .] the idea that Tadzio does not speak (i.e. sing) but only works through his appearance, his personality and his movement, I find altogether ideal.

Discreet and controlled Britten, outwardly as Apollonian as Mann himself, proved perfectly fitting to formulate the age-old antinomy between reason and passion.

Gallery