À la française!

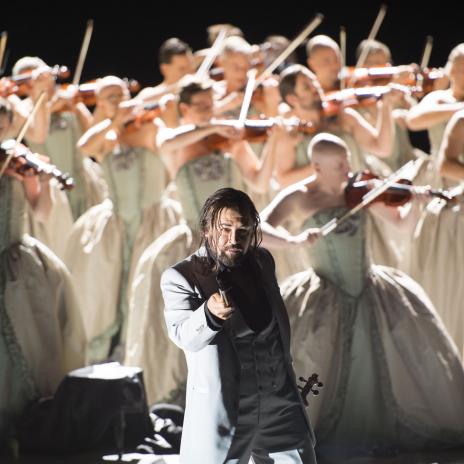

French opera was born in the 17th century out of the golden age of French drama: Corneille, Molière, Racine. What opera added was music, dance and, above all, spectacle. This lavish entertainment revolved around the court of the Sun King Louis XIV in Paris and Versailles. He appointed Italian-born Jean-Baptiste Lully, who had moved to Paris when 14, as royal composer and dance-master at the age of 21. As superintendent of the king’s music, he enjoyed monopoly control, and in 1672 founded the Royal Academy of Music, the official name of the Paris Opera to this day. He invented the 5-act form of lyric tragedy, and between 1674 and 1686 composed a dozen such operas, including Thésée, Atys, Bellérophon (with text by Corneille) and Armide. His regular collaborator was Philippe Quinault, and Lully’s musical settings ensure that the text receives equal prominence. Contemporary musicians such as William Christie, Emmanuelle Haïm, Marc Minkowski and Christophe Rousset have led a successful revival of Lully’s operas.

Lully’s use of a long staff to conduct his music led to his death, after it struck his foot and he contracted gangrene. He refused to have his leg amputated so he could still dance, and it spread to his whole body including his brain.

Lully’s successor was Jean-Philippe Rameau. He was 50 before his first opera Hippolyte et Aricie astounded audiences with its dramatic treatment of the story of Phaedra and Theseus. Despite opposition from traditional Lullistes, during the 30 years between 1733 and 1763 he composed a series of lyric tragedies and opera-ballets which define the baroque. Foremost among them are Les Indes galantes, Castor et Pollux, Dardanus, Platée, Zoroastre and Les Boréades, which was rehearsed but unperformed at his death. Rameau follows Lully in his respect for text, setting Voltaire as well as his more regular collaborator Louis de Cahusac, but offers more sophisticated orchestral colours and rhythmic variety and musical forms imbued with the spirit of the dance.

Rameau was born in Dijon, the seventh of eleven children. He was taught music before he could read or write. He remained a clumsy speaker and never really mastered handwriting. He composed for the church and keyboard until he was 40. Music was his obsession. He claimed: ‘I try to conceal art with art’.

The battle for precedence in French opera towards the end of the 18th century was won by the Bavarian Christoph Willibald Gluck. His ‘reform’ operas aimed to replace baroque ornament with a ‘beautiful simplicity’: Iphigénie en Aulide; his French revisions of his seminal Italian Orfeo ed Euridice for a tenor hero and Alceste; Armide; and Iphigénie en Tauride.

France’s political and economic supremacy during most of the 19th century made Paris the magnet which attracted artists from all over Europe. The years of Napoléon favoured the Italians Luigi Cherubini, best known for his Medée, and Gaspare Spontini, for his La vestale. Foremost among native composers was Etienne Méhul, the first composer to be styled ‘romantic’. Later, the leading Italians were lured to Paris by the challenge and rewards of creating French Grand Opera.

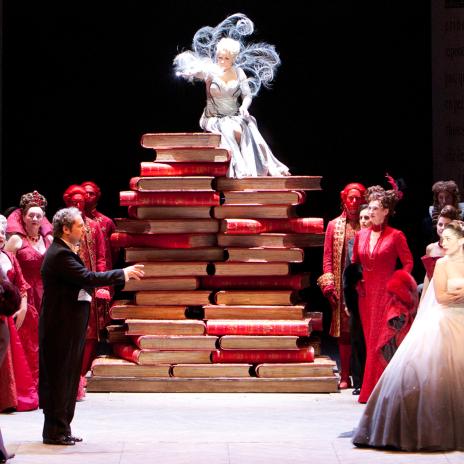

La muette de Portici by Daniel-François Auber, a story of revolution in Naples culminating in the eruption of Mount Vesuvius, was the first ‘grand opera’ in 1828. It is famous for having sparked the real Belgian revolution when performed in Brussels in 1830. It was also the first text for the Paris Opera by Eugène Scribe, who patented the five-act model over the next 35 years. He wrote the text for Fromental Halévy’s La Juive of 1835, but his principal client was the German-born, Italian-educated Giacomo Meyerbeer, whose grandiose works include Robert le diable, Les Huguenots, Le prophète and L’africaine.

Wagner, perhaps influenced by the turbulent reception given to his Tannhäuser at the Paris Opera, belittled the Meyerbeer/Scribe operas as consisting of ‘effects without causes’

It is ironic that the two greatest of ‘grand operas’ composed for the Paris Opera were by Italians at either end of the period: Rossini’s Guillaume Tell (1829) and Verdi’s Don Carlos (1867). More culpably, the greatest of all 5-act French grand operas, Les Troyens by Hector Berlioz, was rejected by the Paris Opera during his lifetime. The most imaginative French composer of the 19th century, his extravagant Benvenuto Cellini met a hostile reception there in 1837. His ‘dramatic symphony’ Roméo et Juliette was given in concert; his ‘dramatic legend’ La damnation de Faust at the Opéra-Comique; and his final comic opera Béatrice et Bénédict in Baden-Baden.

Berlioz’s last words before his death in 1869 were reputed to be: ‘At last, they are going to play my music’

The perfect antidote to ‘grand opera’ was operetta, which flourished during the third quarter of the 19th century. Its arch proponent was a German Jew, Jacques Offenbach, who came to embody and to satirise the carefree spirit of Paris during the Second Empire. Outstanding among his hugely prolific output are Orphée aux Enfers, La Belle Hélène, Barbe-bleue, La vie Parisienne, La Périchole, Fantasio and Les Contes d’Hoffmann. Another delicious opéra bouffe from towards the end of this period is Emmanuel Chabrier’s L’étoile. Their foremost successor was André Messager.

The second half of the 19th century was a ‘silver age’ of French opera. Among the leading ‘craftsman’ composers, and still popular operas, are Charles Gounod (Faust, Mireille, Roméo et Juliette); Ambroise Thomas (Mignon, Hamlet); Camille Saint-Saëns (Le timbre d’argent, Samson et Dalila); and especially Jules Massenet (Manon, Werther, Thaïs, Cendrillon).

One composer stands above the others in this period: Georges Bizet, whose masterpiece Carmen was premièred at the Opéra-Comique two months before he died in 1875 aged 36, so that he never knew that it would become an emblem of a new realism and one of the best-loved of all operas.

‘It is rich. It is precise. It builds, organises, gets finished’: Nietzsche comparing Carmen favourably with Wagner

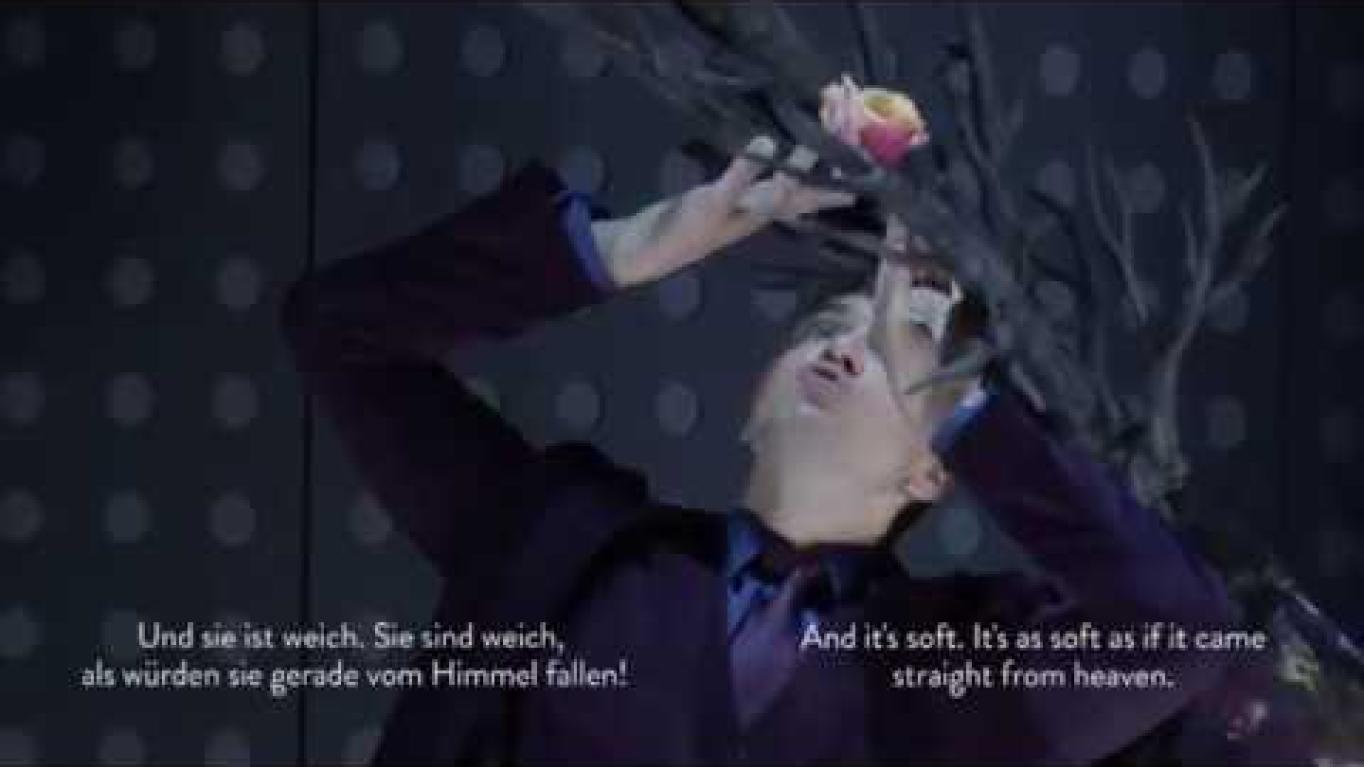

The 20th century brought new perspectives to French music as to the other arts, such as impressionism, pointillism and a repudiation of the recent past. Opera, though important, was only part of their output. The leading composers were Claude Debussy, with his ground-breaking Pelléas et Mélisande, and Maurice Ravel with two short operas, the delicately erotic L’heure espagnole and the child’s fantasy of L’enfant at les sortilèges. Noteworthy contemporary works include Gabriel Fauré’s Pénélope and Ariane et Barbe-bleue by Paul Dukas.

From the second half of the 20th century, the two most enduring French operas have been Dialogues des Carmélites by Francis Poulenc and Saint François d’Assise by Olivier Messiaen. Both are grand spectacles which reflect the values of the past through modern means.