Wagner and Weill

In the pantheon of German opera, Wagner and Weill are polar opposites.

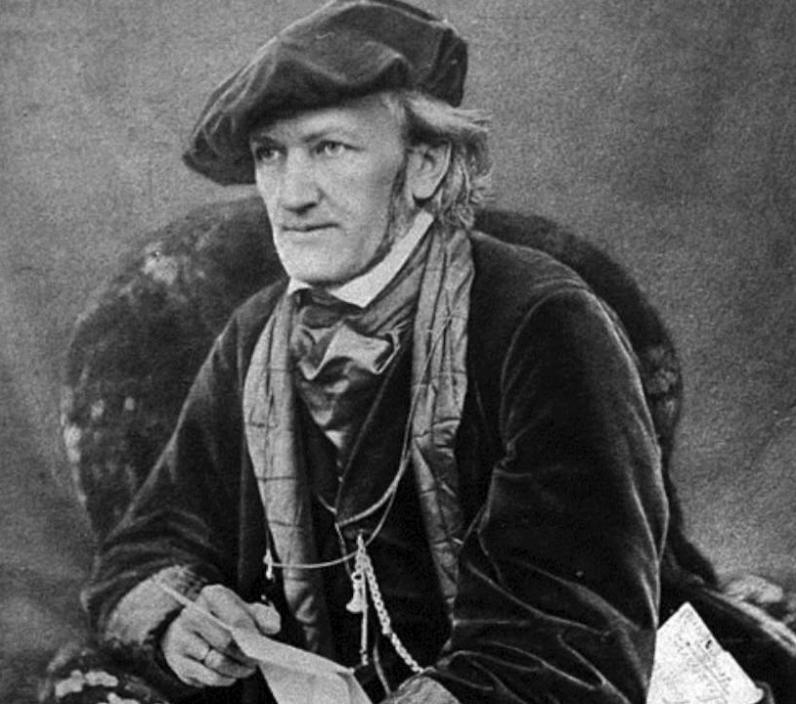

Richard Wagner, despite the controversies surrounding his life and political views, bestrides German opera like a colossus. The canon of his ten mature operas, from The Flying Dutchman to Parsifal, revolutionised opera. His declared purpose of creating a Gesamtkunstwerk, or total work of art, claimed for opera a preeminent position in musical and theatrical life. It adopted a moral purpose. It was no longer entertainment, but a lever to change society. That legacy endures today, 130 years after Wagner’s death.

Wagner cast a long shadow over the work of his successors, not only German composers such as Richard Strauss, nor confined to music, but across the wider world of the arts and politics. His influence is explored in Alex Ross’s magisterial book Wagnerism, published in 2020, whose chapter headings echo the titles and themes of the ten regularly performed operas. Yet, the last century has challenged the dominance of Wagner, repudiated his theories and methods, and given birth to alternative forms of music theatre.

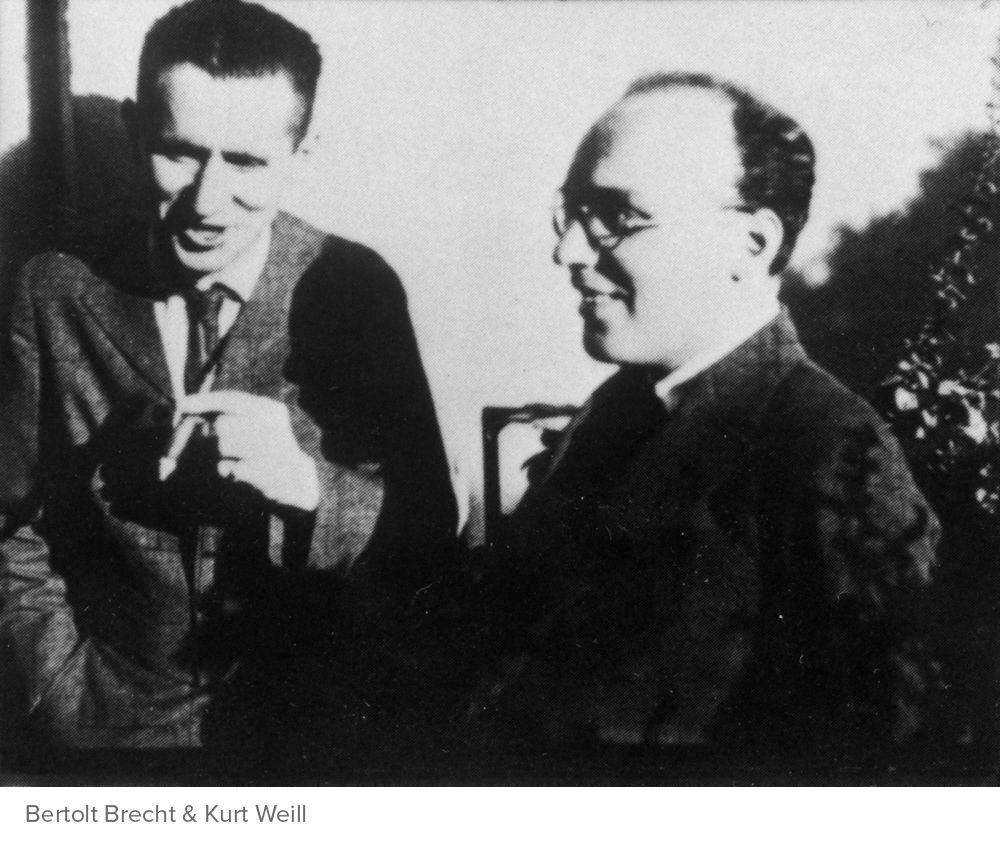

Kurt Weill was born in 1900, the son of a professional synagogue cantor. A formative influence was Ferruccio Busoni, whose masterclasses in Berlin he attended in the early 1920s. Busoni charted a path away from Wagnerian Gesamtkunstwerk towards an ideal derived from Mozart. He called it Ur-Musik, or the essence or spirit of music, informed by past achievements but directed towards future reform. A catalyst in Weill’s development was his collaboration with the playwright Bertolt Brecht, a militant anti-Wagnerian. Yet paradoxically, their joint concern was for opera’s social function.

Brecht and Weill first worked together on the Mahagonny Songspiel of 1927, the germ of what was to become the full-length three-act Rise and Fall of the City of Mahagonny three years later. Brecht’s theory of an ‘epic theatre’ which would lead to the abolition of opera conflicted with Weill’s less draconian reforms, but they managed a reconciliation for a short ‘sung-ballet’, The Seven Deadly Sins, in 1933. By then, Weill was in exile from Germany, and the work was premiered in Paris at the Théâtre des Champs-Elysées. Two years later, he left Europe to settle in the United States.

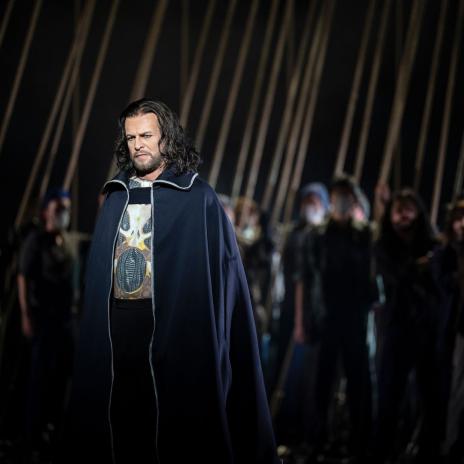

The legend of the Wandering Jew was an inspiration for Heinrich Heine’s From the Memoirs of Herr von Schnabelewopski, which was the principal source for The Flying Dutchman. The opening of the overture, with its arresting open 5ths on tremolo strings in D minor, immediately announces a voice different from any of Wagner’s previous works. The same music launches Senta’s Ballad in Act 2, in which she narrates in three strophic verses the story of the enigmatic wanderer, who returns to shore once every seven years in search of redemption for the curse of eternal exile laid upon him. Other passages in the score are more conventional in style and format, but the chorus scenes in Act 3 regain an extraordinary freedom and vigour. Wagner wrote that the theme of the Norwegian Sailors’ Chorus was suggested to him by the call of the sailors echoing round the granite harbour of Sandviken, where his own ship sought refuge after his perilous voyage of escape from Riga. It is supplanted by the still more chilling response of the Dutchman’s ghost crew, which remains the most thrilling moment in this opera.

Forty years later, Wagner’s journey had concluded with Parsifal, which he described as a ‘stage-consecrating festival play’ for his new theatre in Bayreuth. Based on medieval legend, it is a mixture of Christian and pagan, Buddhism and the philosophy of Schopenhauer. Its decaying community of the Grail temple is a metaphor for the stricken land awaiting renewal. The irony is that its ‘saviour’ is an ‘innocent fool’ who must make his own long journey of wandering and discovery. When Parsifal finally returns to the barren land, he is greeted by the coming of spring, a pantheistic vision of rebirth. Parsifal is immensely more sophisticated, subtle and multi-coloured than The Flying Dutchman, which appears crude by comparison. Yet, both are the preoccupations of an artist who lived the life of a wanderer, never satisfied, always seeking an elusive ‘redemption’, a goal or grail beyond human reach.

Weill was also a displaced artist, the consequence of whose Jewish ancestry was exile from his homeland. Mahagonny is the product of between-the-wars Germany, but it evokes a mythical America with its savage satire of capitalism. Mahagonny ‘the city of nets’ is founded in the desert by three criminals on the run from the police. It is to be a city devoted to pleasure and its motto is ‘nothing barred’. The so-called ‘sins’ of gluttony and lust and fighting and drunkenness are encouraged. The only god is money. So Jimmy Mahoney, the hedonistic lumberjack, is condemned to death for being unable to pay the bill for the whisky he has consumed. Brecht’s moral is: ‘As you make your bed, you must lie on it’; and the bleak final chorus sums up: ‘We can’t help ourselves or you or anyone’.

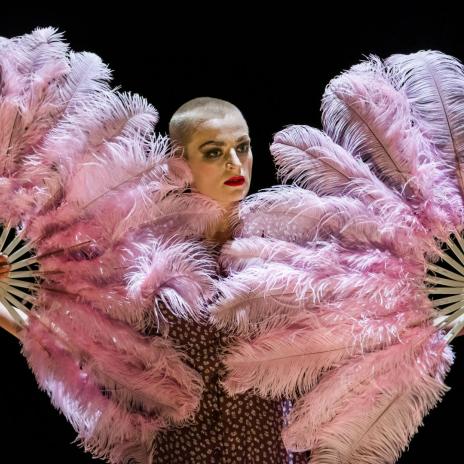

Seven Deadly Sins is more wistful than Mahagonny, perhaps evidence that Weill was escaping not only Germany but the control of Brecht. The heroine Anna is a dual personality, part singer and part dancer. She falls prey to further ‘sins’, including sloth, pride, envy and avarice in addition to those encountered in Mahagonny. Her family urge her to reject them as impediments to making enough money to finance building their home in Louisiana. The triumph of practicality over idealism engenders disillusion with the capitalist dream.

The twist in the tail is that Weill emigrated to the USA, where he composed ten or more stage works – musical plays and comedies and a tragedy, operettas and an opera, even a vaudeville – which were prototypes of the American musical. Stealing the title of Wagner’s essay written in 1849, you might call them ‘The Artwork of the Future’.

Nicholas Payne, March 2022