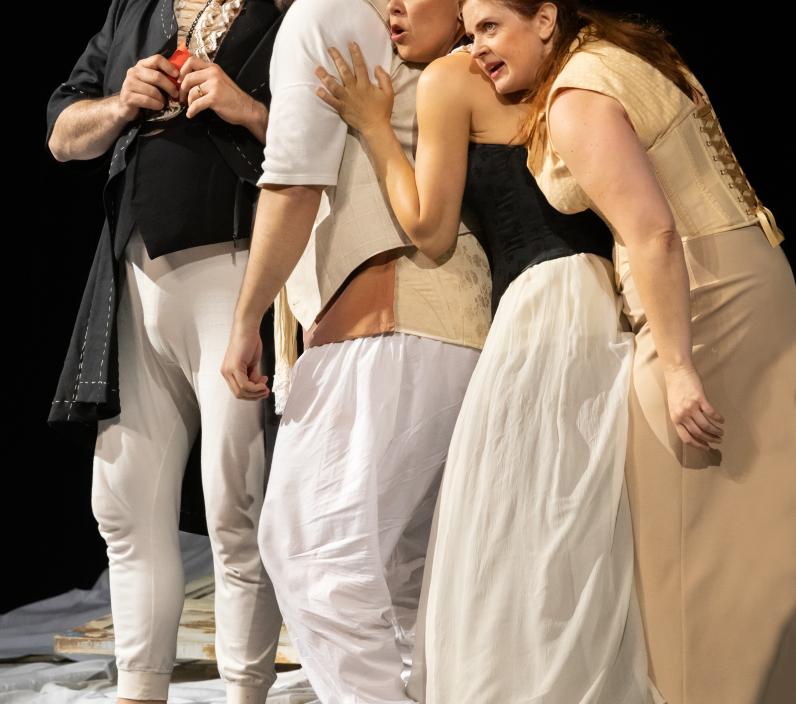

Take a philandering and arrogant Count who is no match for his wily servant Figaro and his soon-to-be-wife Susanna, as manipulative as she is charming. Add in one beautiful, disillusioned Countess and one irrepressible, testosterone-laden teenage boy Cherubino. Mix with the genius of Mozart and you have one of the most perfect operas ever written.

In 1781, the enlightened Emperor Joseph II abolished serfdom, ensuring society’s least privileged – servants like Figaro and Susanna – of certain civil freedoms, including marriage. In their opera, Mozart and his librettist Da Ponte reflect on the remnants of the old guard and look towards a future of greater equality. The Count and Countess might learn a few lessons in love and life from their cunning personnel. Opera Ballet Vlaanderen has entrusted their new production to a youthful artistic team. Director Tom Goossens interweaves the libretto’s original Italian and his own highly imaginative Dutch. The conductor Marie Jacquot is fast becoming an internationally sought-after Mozart specialist. Together they navigate Nozze’s comedy and tragedy, virtuosity, and elaborate twists. As spirited as the opera itself, this is an artistic team to shake up our conventional expectations; like Mozart and Da Ponte themselves, they are respectfully sending up a passing generation. With them, we can ultimately rejoice in Mozart’s message of love, forgiveness and hope.

CAST

Susanna | Maeve Höglund |

|---|---|

Figaro | Božidar Smiljanić |

Contessa | Lenneke Ruiten |

Conte | Kartal Karagedik |

Cherubino | Anna Pennisi |

Marcellina | Eva Van der Gucht |

Bartolo | Stefaan Degand |

Antonio | Stefaan Degand |

Basilio | Daniel Arnaldos |

Marcellina's Lawyer | Reisha Adams |

Bartolo's Lawyer | Yu-Hsiang Hsieh |

Barbarina | Elisa Soster |

Donne I | Sandra Paelinck |

Donne II | Herlinde Van Den Bossche |

Orchestra | Symfonisch Orkest Opera Ballet Vlaanderen |

Chorus | Koor Opera Ballet Vlaanderen |

| ... | |

Music | Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart |

|---|---|

Text | Lorenzo da Ponte |

Conductor | Marie Jacquot |

Director | Tom Goossens |

Sets | Sammy Van den Heuvel |

Dramaturgy | Lalina Goddard Tom Swaak |

Costume | Dotje Demuynck |

Lighting | Luc Schaltin |

Choreography | Darren Ross |

Chorus Master | Jan Schweiger |

| ... | |

Videos

STORY

Act I

It is the day of Figaro’s marriage to Susanna, maid to the Countess. Figaro, valet to the Count, is assessing the bedroom offered to him by his employer; it conveniently adjoins both the Count’s and the Countess’s apartments. Susanna points out that the room will also be ‘convenient’ when the Count chooses to reinstate the ‘Droit de Seigneur’, a feudal practice in which a local Count can ‘deflower the bride;’ a practice that he has recently abolished. Figaro determines to outwit his master.

But Figaro owes money to Marcellina, and has promised to marry her if he does not manage to repay her. He has also raised the ire of Dr. Bartolo, the Countess’s former guardian, for his role in helping bring about the Count’s marriage to the Countess. To complicate matters further, the young page Cherubino wants Susanna to intercede on his behalf with the Count, who has dismissed him from the castle after catching him alone with Antonio’s daughter, Barbarina.

Suddenly the Count shows up, causing disarray. Cherubino hides and hears the Count’s overtures to Susanna. The Count in turn hides, and overhears Basilio, the music master, making insinuations about Cherubino and the Countess. The Count emerges, discovers the unfortunate page, and sends him to rejoin his regiment.

Act II

A weeping Countess laments the loss of the Count’s love. Figaro reveals his plan to outwit the Count: he has sent him an anonymous letter implying that the Countess has a lover. Susanna points out that Marcellina can still invoke the debt and stop the wedding, and a second plan is hatched. Susanna will agree to meet the Count in the garden, but Cherubino will go disguised in her place. Figaro instructs the women to dress Cherubino appropriately.

The page flirts with the ladies by singing his latest composition. When he is half undressed, the Count arrives. Having received Figaro’s letter, he is in a jealous rage. Cherubino, hidden in the closet, knocks over a chair. The Countess, in a panic, pretends that the noise is Susanna, but refuses to unlock the door; meanwhile, Susanna rescues Cherubino, who escapes out of the window. Susanna locks herself in the closet.

The Countess attempts to explain to her husband the presence of Cherubino in her closet. She is as surprised as the Count when it is Susanna who emerges. The two women pretend that the whole episode was a trick to provoke the Count into better treatment of his wife. They confess that the letter was written by Figaro, who then joins them, unaware of the women’s revelations to the Count. When Bartolo, Basilio and Marcellina arrive with a lawsuit to force Figaro’s marriage to Marcellina, the Count is triumphant.

Act III

The Countess and Susanna open the third act with a plan to disrupt the Count’s amorous intentions. Susanna will agree to meet the Count that evening in the garden, but the Countess will go in her place, disguised as her maid.

On the advice of his legal consultant, Don Curzio, the Count insists that Figaro pay Marcellina at once or marry her. Figaro is saved by the timely revelation that he is the long-lost son of Marcellina and Bartolo; everyone but the Count and Don Curzio embraces their new relations.

Finally the wedding celebrations of Figaro and Susanna begin. Cherubino is unmasked among the bridesmaids, but Barbarina shames the Count into allowing him to stay at the castle. Susanna passes the Count the letter dictated by the Countess, confirming her evening rendezvous with him under the pine trees.

Act IV

In the garden everybody is waiting: the Count and Figaro for Susanna; the Countess for the Count; Bartolo and Basilio to witness the revival of the ‘Droit de Seigneur.’ Figaro rails against the faithlessness of Susanna, while she looks forward to the conclusion of her plans.

The appearance of Cherubino is potentially disastrous, but the Count arrives and woos ‘Susanna,’ in fact his wife. The jealous Figaro is then confronted by Susanna, disguised as the Countess, but he recognises his bride and they are reconciled – witnessed by the Count, who believes he sees his wife in the arms of his valet. He denounces her; the real Countess unmasks herself and forgives her husband. The day ends in celebration.

Insights

The Wedding Unveiled

How far can you go in the adaptation of an opera? And what takes precedence: the music or the text? As they prepare their new production of Le nozze di Figaro, conductor Marie Jacquot and director Tom Goossens discuss.

Tom Goossens - For me, it all started when I was eight years old. My father, an opera fanatic, then showed me his favourite opera Don Giovanni for the first time in Peter Sellars' TV adaptation. That was my first opera experience and I was fascinated by the music. For those first six years, I did not listen to any other opera! From the age of 14, when I began to fall in love myself, I suddenly began to recognise myself in the story and in characters like Elvira.

Marie Jacquot - Haha, brilliant! That sounds like an excellent upbringing from your father.

TG - My father is a biologist and my mother teaches biology. My mother definitely doesn't like opera.

MJ - I don't come from a musical family either. We all had to learn to play an instrument and play a sport at home, my father told us. As a teenager, I thought I wanted to become a professional tennis player, I even played at Roland Garros. But I got tired of the competitiveness of it, so then I resolutely chose to devote myself to the trombone in Paris. I played in orchestras for a while, which I particularly enjoyed. I took conducting lessons, went to Vienna and so I became a conductor. That's the story in a nutshell. In the beginning, I hated - really hated - opera. I dreamed of the great symphonic work: Mahler and Bruckner. Until I got an invitation, even though I had never done one before, to conduct an opera in Würzburg. To top it all off, I was then hired there as Kapellmeisterin. I stayed there for three years, then three years in Düsseldorf. Now, of course, I love opera immensely. I can no longer imagine a career without opera.

TG - It's crazy that I only found out so late that I wanted to be an opera director. Not only did I love opera very early on, but also theatre. I was intrigued by how it was all made. A bit like you, at 18 I had to choose between two passions: flute and theatre. Then I thought that in opera I could do both music and theatre.

MJ - A director who can read music!

TG - Reading music is not a problem. I also love the music immensely, for me it is the foundation, also for directing. Although it remains a great challenge to perform a comedy with orchestra. In comedy, timing is everything. As soon as an orchestra comes in, the actors on stage cannot be guided by their own spontaneous sense of timing. The tempo of the music dictates the performance, and not the other way around.

MJ - I have heard from many directors that comedy is the most difficult.

TG - Yes, I think so. Through my theatre adaptations, I know that language is also a very important factor here. After all, humour works better in the language of your audience. To generate laughter today, the connection with your audience is extremely important. It works best when the audience feels alive with the performer in the same moment. We have therefore thought thoroughly about how to be as generous as possible, allowing a strong connection between the players and the audience. We did an extensive study of sightlines, both in Ghent and Antwerp. We sat down in all possible places in the auditorium, from the parterre to the boxes, from the first side balcony to the very highest rows. We determined what we could or could not see, together with, among others, scenographer Sammy Van den Heuvel and technical designer Eva Florizoone. So we delineated a playing surface on stage that was visible to everyone, the greatest common denominator. That turned out to be a narrow, wedge-shaped strip running across the centre of the stage. That is where we will have the central action take place, so that everyone in the whole room can follow the whole story. This is the general premise of our production: not so much ‘what idea can I put on top of the existing material?’, but rather ‘how do we unlock the riches that are already there in the best possible way?’ I won't give everything away just yet, but that is a guideline that really every member of the artistic team followed.

MJ - It may sound obvious, but I also interpret what is there. You can play quieter or louder, put an accent here or there, that's interpretation. But I don't want to rewrite the piece and I certainly don't want to make anything 'new' just because we need to be new. So I recognise that I am an interpreter, but I always try to do what is written. There are also conductors who put their ideas on top of it; I try to serve the composition. As for comedy, I feel that for me a lot depends on the interaction with the stage, with the direction and the singers and actors. I see myself as a chameleon: I adapt to what the project asks of me.

TG - Totally agree. By the way, our motto 'working with what is given' does not mean that we strive for a museum-like performance in which everything is historically accurate. No, we also - as is our custom - make cuts or even translate the roles of Bartolo and Marcellina into Dutch, but these changes never stem from our egos or our own intellectual theories or anything like that. I hope this doesn't sound arrogant, but sometimes you just don't have to do everything blindly to do the work more justice. Today's audiences are different from those in the days of Mozart and Da Ponte. Different things are funny today than they were then, that's just the way it is. Also, the original Figaro trilogy by playwright Pierre Beaumarchais is probably less well known now. In 1783, Giovanni Paisiello's operatic adaptation of the first part, Il barbiere di Siviglia, premiered in Vienna and in the years that followed, the opera was performed more than a hundred times. When Mozart and Da Ponte came up with their Le nozze di Figaro in Vienna in 1786, it must have been clear to spectators that this was the second part of the Figaro trilogy. They knew the characters, their antecedents, and thus sat in the audience with prior knowledge and different expectations. Now, for example, if you want the opening recitative of Bartolo and Marcellina - which builds on what happened in the first part - to work the same way, you have to start adjusting things. That's why I chose to translate their roles, the two most comic characters from Le nozze di Figaro, into Dutch and have them played by top actors: Eva van der Gucht and Stefaan Degand. The audience wants to understand the story and we have to give them that understanding. So at such a moment, rewriting is not being unfaithful to the original. On the contrary, you are more faithful than if you didn't.

MJ - Yes, we shouldn't forget that we live in a different time and we have to adapt to it. Today's viewer is used to films in which shots are constantly and lightning-fastly changed, the pace is very fast and we get impatient if something is dragged out for too long. We should aim for that immediacy too.

TG - Everything points to that being exactly what Mozart was trying to do. He was so strong formally and managed brilliantly to constantly excite and surprise the audience.

MJ - Exactly, and we are used to a lot of stimuli today. Just watch how quickly people reach for their smartphones when they have to wait somewhere for more than a minute. On top of that, we actually treat opera strangely now: it used to be a social event, you listened and watched, you talked to people or even ate something in between. Today, we think we have to sit and watch in concentration, in silence. That's why I think it's a bit arrogant if, as a conductor, you insist on not making any cuts and wanting to include all the added arias and the like. If something takes too long, you lose part of your audience and basically force them to sit out the performance. This is why I sometimes have a hard time with Wagner: his music is sacred to Wagnerians and you can't or shouldn't delete a single measure from it. By doing so, you exclude a large part of your audience from the outset: for someone who is not yet a lover, it is not natural to digest five hours of opera.

TG - For me, Wagner can have something very meditative, but we should indeed recognise that viewing habits have changed and not idolise the length of an opera. If you watch Netflix continuously for an hour and a half, you get a message asking if you are still there. We have to fight against that. An opera house is a good place for that. You can get into a different concentration from that of everyday life there. I love the music immensely, for me it is the foundation for directing. Although it remains a great challenge to perform a comedy with an orchestra.

Adapted from an interview by Tom Swaak.

GALLERY