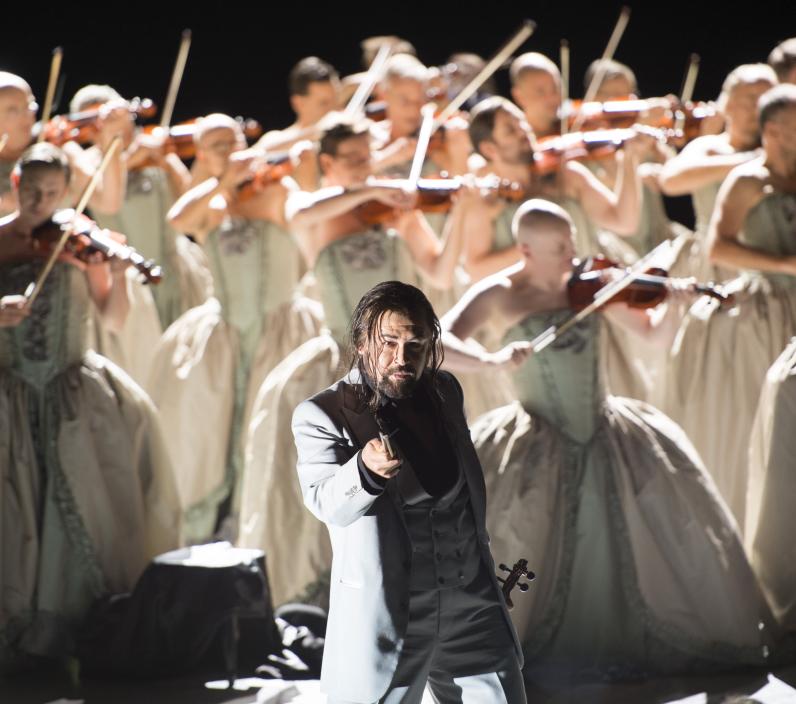

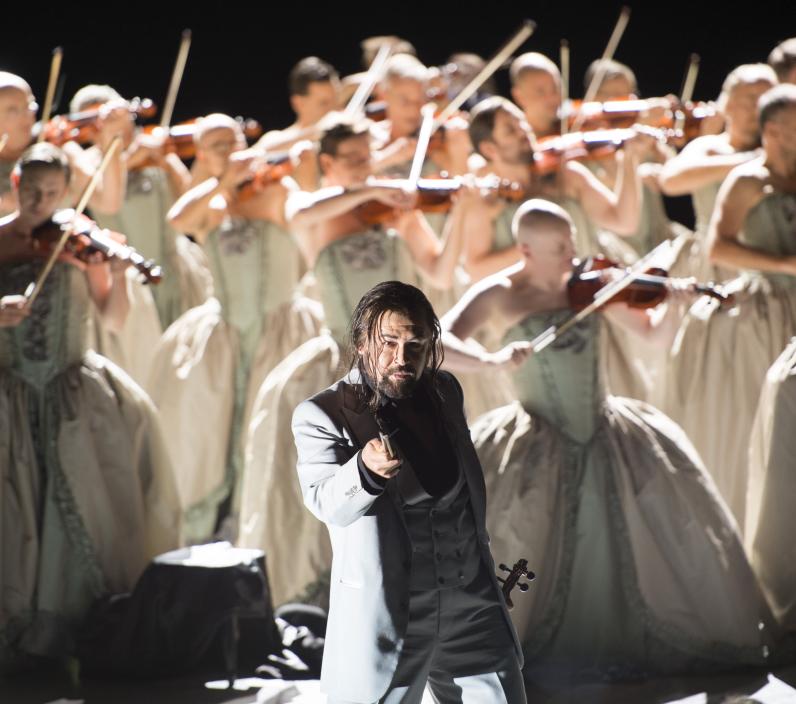

The Tales of Hoffmann

In a poet's feverish imagination, the staging of Don Giovanni sets him off on a frenzied journey into nightmarish worlds. Can Mozart himself offer him salvation as he loses himself in his fearful dreams?

Barrie Kosky tells Offenbach's fantastic story as a disturbing nightmare of an artist who increasingly loses his sense of identity. As we dive into the obsessions of a deranged mind, the title role itself is shared by three performers - including an actor - while a single soprano embodies all four female lead roles.

Cast

|

Hoffmann 1

|

Uwe Schönbeck

|

|---|---|

|

Hoffmann 2

|

Dominik Köninger

|

|

Hoffmann 3

|

Edgaras Montvidas

|

|

Stella / Olympia / Antonia / Giulietta

|

Nicole Chevalier

|

|

The Muse

|

Karolina Gumos

|

|

Lindorf / Coppélius / Doctor Miracle / Dapertutto

|

Dimitry Ivashchenko

|

|

Andrès / Spalanzani / Frantz / Pitichinaccio

|

Peter Renz

|

|

Cochenille / Crespel / Peter Schlémil

|

Philipp Meierhöfer

|

|

Antonia's Mother

|

Karolina Gumos

|

|

Chorus

|

Chorsolisten der Komischen Oper Berlin

|

| ... | |

|

Music

|

Jacques Offenbach

|

|---|---|

|

Conductor

|

Antonino Fogliani

|

|

Director

|

Barrie Kosky

|

|

Sets

|

Katrin Lea Tag

|

|

Lighting

|

Diego Leetz

|

|

Costumes

|

Katrin Lea Tag

|

|

Text

|

Jules Barbier

|

|

Chorus master

|

David Cavelius

|

| ... | |

Video

The story

The inflated imagination of the poet Hoffmann turns a staging of Mozart's Don Giovanni into the starting point of a crazed journey through bizarre worlds.

Hoffmann's obsessive admiration for the singer Stella, who plays Donna Anna, gives rise to a number of female figures: the puppet Olympia, who presents soulless feats; the singer Antonia, who sings herself to death; the courtesan Giulietta, who steals Hoffmann's mirror image. Bizarre nocturnal creatures, such as Olympia's creator Spalanzani or the terrifying eye salesman Coppelius, Antonia's strict father Crespel or the diabolical Doctor Mirakel, the frantic Pitichinaccio or the dubious Dapertutto, turn Hoffmann's imaginary journey into a nightmarish horror trip.

In the end even Mozart can no longer save Hoffmann. Chased by his own demons, he has long since lost himself in his fantasies and fearful dreams.

Insights

Hoffmann's doppelgangers

Barrie Kosky's refreshing take on Offenbach's last opera

With Les Contes d'Hoffmann, does Offenbach finally become a serious composer?

‘Contrary to the popular belief that Offenbach left operetta behind with his last work in order to become a serious (opera) composer at the end of his life, I see no difference between the Offenbach of the Opéras bouffes and that of the Contes. He was a serious composer even before that, because the scores of La Vie parisienne, Orphée aux enfers or La Belle Hélène are 'serious' because they are brilliant masterpieces.’

Les Contes d'Hoffmann are thus the logical consequence of Offenbach's earlier compositional work.

‘There are also comic and parodic moments in Les Contes d'Hoffmann, but it is a different comedy from that of Belle Hélène or Grande Duchesse de Gérolstein. The warm comedy of the operettas has become a grotesque, biting comedy à la E. T. A. Hoffmann. The light opéra bouffe has turned into an opérette grotesque in the Contes.’

Isn’t Hoffmann a deeply unsympathetic character?

‘I find the Hoffmann of the opera incredibly unsympathetic as a character. A drunken, depressed man, full of self-pity, lurching from one narcissistic moment to the next for three hours. It doesn't move me, in fact it bores me increasingly as the evening goes on.’

Kosky's solution? He added a speaking part, dispensed with the opera's original dialogue and instead had the original E. T. A. Hoffmann speak through his own words.

‘In this way it was possible to let the whole world of this opera with all its characters come into being, as it were, in the imagination of the added Hoffmann figure. This lonely man lost in his fantasies can credibly show emotions without drowning in the self-pity of a 'poor poet'.’

You think one Hoffmann is too much? How about three?

To illustrate Hoffmann's loss of identity and to take up the romantic idea of the doppelganger, Kosky has three actors appear in the title role.

‘It was almost a twist of fate when, in the course of the preparations, we discovered that Offenbach had originally planned the title role for baritone and that the first two acts of the opera are actually available in a baritone version. Simply dividing the vocal part between two tenors would never have been an option for me. But with three vocally different Hoffmann characters, the piece takes on a whole new dimension for me.’

Three actors for one Hoffmann, fair enough. But a single singer for the four adored women?

‘Not only are the villains a product of Hoffmann's imagination, so are the women. In reality, none of them exist. Not even Stella. She is Hoffmann's projection of an ideal stage artist. She is the voice made flesh. In the three other women, Hoffmann tries to find this ideal woman again. But it is not interesting to follow a man on his search for the perfect woman for three hours.‘

Underneath, however, lies something more interesting:

‘The heterosexual man's relationship with women is shaped by his own fears; his fear of impotence, his awareness of his own mortality - fears that he projects onto the opposite sex. Les Contes d'Hoffmann is not about the relationship between women and men, but about one man's fears of loss: Hoffmann.’

Gallery