Only that which is dull and dry is false

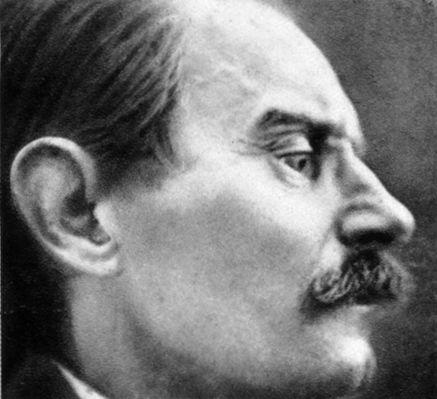

Ivan Acher’s new Esperanto-language opera Sternenhoch is based on Ladislav Klíma’s unconventional novel The Sufferings of Prince Sternenhoch. But who exactly was its author? Journalist Jiří Peňás looks at the life, works and legacy of the legendary Czech eccentric.

The Sufferings of Prince Sternenhoch was written by Ladislav Klíma sometime between 1907 and 1909. The author himself called it a ‘grotesque romanetto’. In his approximately thirty years of life, he had already published his philosophical text, The World as Consciousness and Nothing, which provoked the interest of a number of his fellow scholars. Many of them kept their faith in Klíma, supporting him during the times when he did not have a penny to his name.

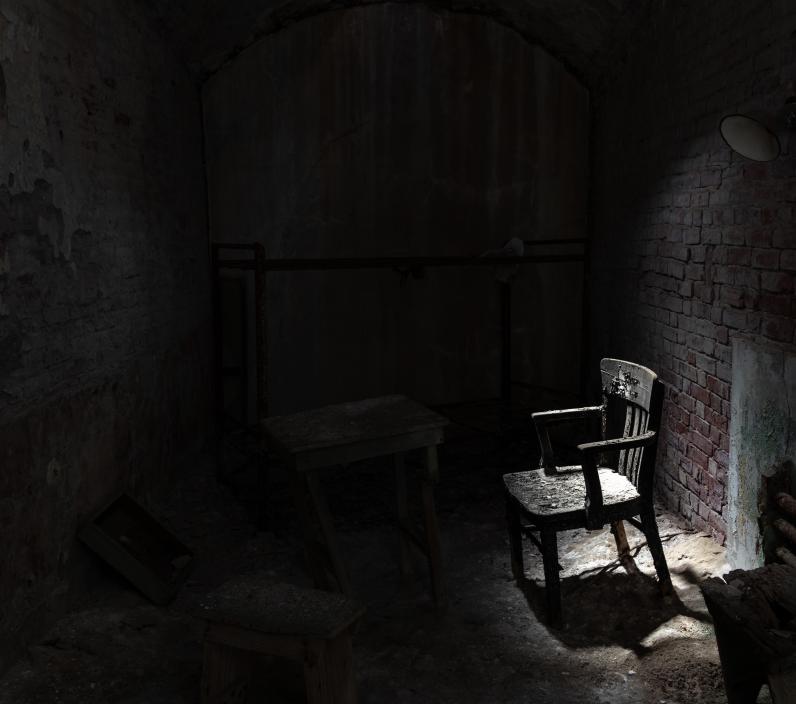

At that time, he was yet to become the Klíma of later years – a shabby, vagabond individual addicted to alcohol and nicotine who was living in a destitute room at the Krása Hotel in the Vysočany district of Prague and subjecting his own body to cruel experiments as a part of his philosophical discipline. He was yet to become that man, but what was already present was his radical nature and strict refusal of what could be called a ‘normal life’.

As a devotee of Schopenhauer and Nietzsche, Klíma sought and cultivated a philosophy of his own, one that would lead him to the edge of the abyss and beyond. He saw himself as a philosopher in the Ancient Greek tradition, journeying through life completely independent of the world around him and summarising his personal philosophy in a single major work. He spent a great deal of time writing fiction, perhaps truly believing that he would make his living that way. Later, he saw it as a rather embarrassing error of judgment on his part.

For the rest of his life, Klíma thoroughly despised professional writing and all ‘profane’ activities in general. The reason might well have been his own experience of how easy it was for him to write. Creative work was quite natural to him and he could have achieved anything in the world of literature had he wished to. He had no problem piling pages upon pages of colorful narration, as anyone who has read his largest work, The Great Novel, can attest to. But that was not enough for a man of his ambition. To him, fiction was a mere medium for communicating philosophical ideas.

The non-conformist work of Ladislav Klíma has almost always shocked, has often incited scandal, but has hardly ever left us indifferent. One need not accept his view of the world to experience it and enjoy it in all of its ambiguity.

Being a metaphysical crime story, Sternenhoch is both mad and deeply realistic – with reality being viewed in an extremely curved mirror. It tells the tale of the insane, demented and degenerated Prince Sternenhoch, who madly falls for Helga, a demonic brat yearning for the absolute Will in her sadistic inclinations. She despises the whole world, takes revenge on her father and has nothing but bitter hatred for Sternenhoch. She smashes the skull of their infant child and is masochistically devoted to her lover, who – in spite of his macho attitude – is nothing more than a bum. In a fit of jealousy, Sternenhoch murders Helga but she keeps coming back as a revenant and hallucination that the poor and idiotic prince struggles with helplessly. In the end, he achieves some kind of redemption when his suffering and madness liberates him from fearful clutching to life. He becomes one with Helga’s decomposing body by throwing away his own life, which was completely worthless in the first place.

Klíma tried to have his manuscript published on several occasions but failed. It was not until 1928, a short time after the author’s death, that Sternenhoch came to print. The work attracted little if any attention. Perhaps the time was not favourable: the literary canon was different, all modernism and functionalism – the exact opposite of the novel’s bizarre romanticism. It is true that Klíma had his admirers, including F. X. Šalda and Karel Čapek, who contributed a polite obituary, but critics did not know how to interpret his prosaic style.

In the fifties and sixties, Sternenhoch‘s existentialism, absurd nature and one-of-a-kind black humor was rediscovered, becoming a treasured text for the era. Its author became a darling of alternative intellectuals, loved by Bohumil Hrabal and influential on writers such as Egon Bondy. Klíma became something of an idol for the underground, where he was seen as a predecessor of the hippie-like counterculture of self-destructive drinkers who viewed mainstream society with deep cynicism.

For those who experience them, Klíma’s works often become a passion, an addiction and a haunting riddle. This most radical of the philosophers to have lived in Bohemia, this ‘thinker of the unthinkable’, opens innumerable ways of interpretation, one of which portrays the world as a ball to be played with in a ruleless game by supreme child-god creators. Such a game is part of the ecstasy shining upon the world: One gesture to make the world, the other to unmake it, and all governed by nothing but the creator’s free will.

In this process of creation, a metaphysical vision becomes artistic. Theatre is one of the forms that it may take – but as theatre’s more eccentric sister, opera is better still. It is impossible to speak on Klíma’s behalf, but it would be very surprising if he did not love Ivan Acher’s Sternenhoch and especially the philosophical passion of Vanda Šípová’s Helga. It is just like Klíma himself wrote: ‘Understood on the deep and internal level, everything that is interesting is true. Only that which is dull, dry and dead is false. Such is the psychological truth, the truth of living things.’ And Acher’s opera is everything but ‘dull’ or ‘dry’, as you’ll see for yourselves.

This article first appeared in National Theatre Prague’s Opera Nova journal in June 2019.

▶ Sternenhoch - Watch the full performance on OperaVision from 27 September 2019 to 26 March 2020.