Who is Cassandra?

In one of the most intriguing scenes in Bernard Foccroulle’s Cassandra, the mythological protagonist lingers in the library of the dead. Stoically, she declares that the books that surround her do not tell her full story. But who then is Cassandra? Who is this woman who, with her gift and her curse, captured the imagination of so many of our literary forebears and lives on today in countless stories and retellings – including a new opera?

CAUGHT FOREVER IN THESE WORDS OF MADNESS …

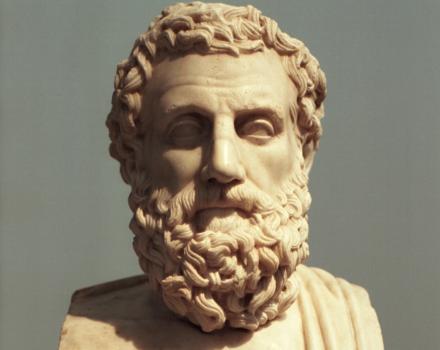

Cassandra is one of the daughters of King Priam of Troy. A priestess, she dedicates her life to the god Apollo, who, in the oldest and commonest versions of the myth, falls in love with her. To win her love, he endows her with the gift of foretelling the future. However, when the priestess rejects his advances, his anger knows no bounds. Nobody, not even Apollo, can ever revoke a divine gift, but by spitting in her mouth, he does manage to put a curse on her so that no one will ever believe Cassandra’s predications again.

In his tragedy Agamemnon, Aeschylus has us believe that she only has herself to blame for the curse. When the chorus asks her why she is uttering unintelligible words, her language suddenly becomes clear: ‘It is Apollon who makes me speak like this … (He) fought for my love... I promised him (my favours) – I did not grant them. … Since I misled him, nobody believes me anymore.’ Other versions of the myth perpetuate the doubt about this alleged breach of promise (did Cassandra really ask for that reward?), and even suggest that she was in possession of her gift before she met Apollo.

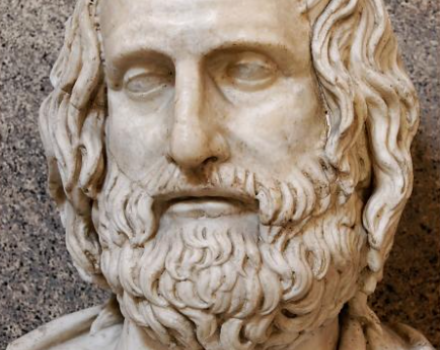

According to the Ancient Greek and Roman epic and tragedy, the curse came at great cost to Cassandra and her people during the Trojan War. Not only did Cassandra predict to no avail that the marriage of Paris and Helen would eventually cause the city to burn, she also warned that the gigantic wooden horse standing before the gates of Troy - the Greeks’ ultimate ruse - should not be taken inside the city. In Virgil’s Aeneid, Cassandra shouts out her predictions of disaster in a kind of trance. She is characterised in a similar way in the tragedies about her life after the war. For example, in The Trojan Women, Euripides recounts how Cassandra and her mother Hecuba are carried off one by one. Cassandra’s abduction is particularly violent: having first assaulted her, the Greek hero Ajax drags her by the hair out of the temple of Athena only to have the Mycenaean king Agamemnon take her away to his kingdom. However, Cassandra, who is labelled “possessed” and “mad” by several characters in Euripides’ tragedy, does not deplore her fate and, to everyone’s amazement, calls for dancing, before confusingly predicting how she and Agamemnon will die on arrival in Mycenae:

‘IF THE GODS EXIST, I WILL BECOME A TERROR WORSE THAN HELEN TO THE FAMOUS AGAMEMNON: I WILL SLAY HIM. I WILL WIPE OUT HIS FAMILY … THE HORROR … NO. I WILL NOT TELL OF THE HORROR. I WILL NOT SPEAK OF THE AXE THAT SEVERS MY NECK (AND SOMEONE ELSE’S TOO).’

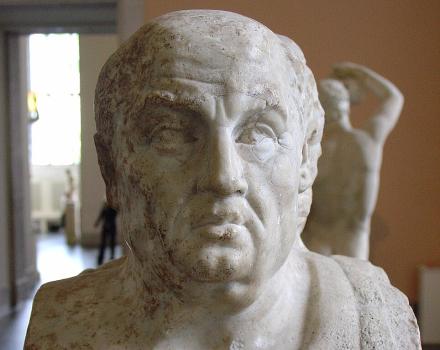

That prophesy is fulfilled in Aeschylus’ and Seneca’s tragedies Agamemnon, which centre on the murder of this Greek king. Indeed, awaiting him at home is a revengeful wife, who has not forgotten that he sacrificed their daughter Iphigenia so as to sail to Troy with a favourable wind. Now she will sacrifice Agamemnon – and with him his new slave. When Cassandra goes ashore in Mycenae, she predicts her impending doom as an insane woman, who - according to Seneca - ‘swoons’, -‘trembles with reeling neck’ and prophesies ‘in a wild frenzy’. Though Cassandra can clearly visualise her own death, even this prediction is never taken seriously by the bystanders in the tragedy. Indeed, in Aeschylus’ version, the chorus’ reaction is one of confusion, saying that it does not understand her, explaining once again the tragic curse that will afflict her to the end of her days: ‘We know that you can predict – woman. But we do not wish to hear your prediction.’

… TRAPPED BY PENS IN THE MINDS OF MEN.

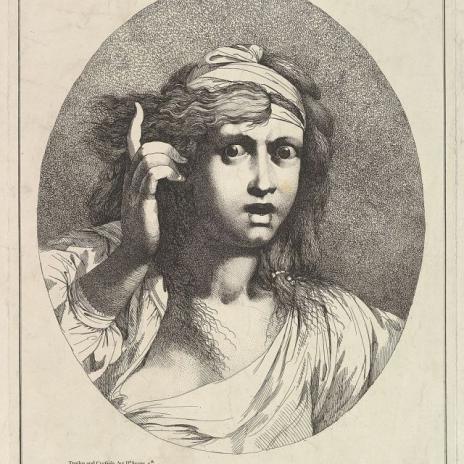

In modern retellings of the myth, that stereotypical characterisation of Cassandra as a crazy, prophesying woman gradually tones down, while the particular focus on the bystanders’ ‘not wanting to hear’ grows.

For instance, the novel A Thousand Ships (2019), in which the British writer Natalie Haynes tells the story of the Trojan War through the eyes of all the female characters, introduces us to a much more serene Cassandra. In this version, she does not shout, but whispers, mainly out of fear for her family’s reactions. This however is unjustified: when Cassandra mutters about one of her visions, no one – not once – even looks up or shows any interest in listening to her. And when her prediction is inevitably fulfilled, Haynes is very clear about the intrinsic indifference of the Trojans: ‘Somehow they all forgot that Cassandra had told them this was coming and they persuaded themselves that she had claimed something completely different.’

Stephen Fry emphasises this point even more in his popular adaption Troy. In the famous scene where the Trojans hesitate as to whether or not to accept the wooden horse, the debate continues calmly, regardless of the frustrated Cassandra’s shouts that the contents of the horse will ultimately lead to the destruction of their city. Her presence draws not so much as a glance, a raised eyebrow or any other acknowledgment of her presence. And Fry even touches on a feminist stance : when Apollo tries to violate Cassandra’s beauty, she speaks in no uncertain 21st-century terms: ‘No! I do not consent!’.

Cassandra’s artistic team was also inspired by the princess’ trajectory since classical literature – from tragic, hysterical figure to someone trying to reclaim her agency – and by an awareness of the ‘male gaze’ that has dominated her historically. ‘In some classical sources, Cassandra is not believed because she is hysterical, while in other sources she simply speaks a different language,’ explains dramaturge Louis Geisler. ‘Either way, the blame always lies with her, while it is actually the public and the bystanders who do not want to hear or understand her because deep down they know that her predictions are sound.’

— CHORUS

‘Why does this fear hover

at the threshold of my heart? –

hungry for signs of the future,

singing some prophetic song

uninvited and unwelcome.’

(…)

— SANDRA

Deep down, the chorus must sense…

— BLAKE

Yes, deep down,

the chorus too knows the future.

— Cassandra (scene 5)

Moreover, the makers of the opera identified parallels with today’s young, predominantly female climate activists. They, too, usually see their calls for action dismissed as female hysteria and youthful naivety. The makers have transposed that tragedy to a modern counterpart of Cassandra: climate scientist Sandra. She does stand-up comedy as a way of disseminating her views on climate. She uses humour to make herself heard and believed, but above all to urge people to act. When Cassandra’s curse also seems to hang over Sandra’s life and their fates eventually even threaten to coincide, we witness the ultimate encounter between the two women – beyond the borders of time, space and veracity. There the appearance of Cassandra assures her that, freed of the spitting gods, she has everything it takes to make a difference:

‘BUT NOW, SANDRA, THERE IS NO GOD TO SPIT IN YOUR MOUTH. NO, NO-ONE EVER, WILL TAKE YOUR VOICE AWAY’.

With this statement, Cassandra speaks not only to her modern counterpart, but to all of us. With the message that in 2023 we still have the opportunity to tackle present and future environmental issues, the opera Cassandra adds an extra dimension to the mythological character on which it is based: from now on Cassandra personifies not only tragedy, but also the hope that her curse can still be broken.

———

Eline Hadermann