Elektra

Queen Clytemnestra assassinates King Agamemnon. Their daughter, Elektra, lives for the day when her father's death will be avenged. Like a curse, the vendetta must be fulfilled, but is Elektra capable of committing the irreparable?

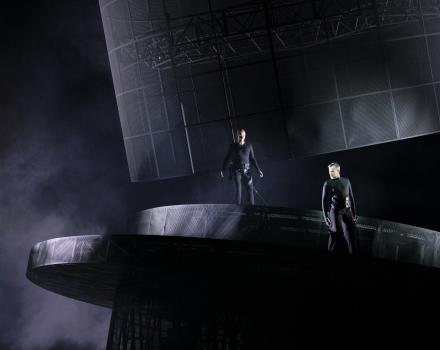

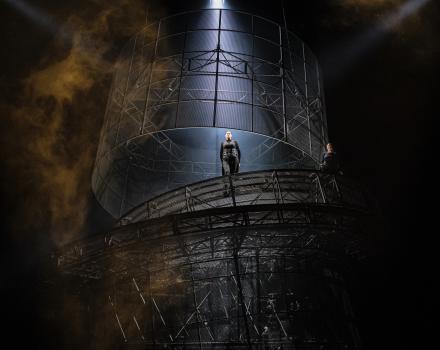

At Grand Théâtre de Genève, the cogs of revenge are set in motion by director Ulrich Rasche, who imprisons the characters of Elektra in a spectacular scenic device: a steel tower weighing almost twelve tons in perpetual rotation. In the pit, conductor Jonathan Nott and his Orchestre de la Suisse Romande confront the musical challenges of Strauss' intoxicating one-act score. The female characters at the centre of the drama are sung by three artists of the highest calibre: Ingela Brimberg as Elektra, Sara Jakubiak as Chrysothemis and Tanja Ariane Baumgartner as Clytemnestra.

Cast

|

Electra

|

Ingela Brimberg

|

|---|---|

|

Clytemnestra

|

Tanja Ariane Baumgartner

|

|

Chrysothemis

|

Sara Jakubiak

|

|

Aegisthus

|

Michael Laurenz

|

|

Orest

|

Károly Szemerédy

|

|

Orest's tutor

|

Michael Mofidian

|

|

The confidante

|

Elise Bédènes

|

|

The trainbearer

|

Mayako Ito

|

|

A young servant

|

Julien Henric

|

|

An old servant

|

Dimitri Tikhonov

|

|

An overseer

|

Marion Ammann

|

|

Five maids

|

Marta Fontanals-Simmons, Ahlima Mhamdi, Céline Kot, Iulia Elena Surdu, Gwendoline Blondeel

|

|

Chorus

|

Grand Théâtre de Genève Chorus

|

|

Orchestra

|

Orchestre de la Suisse Romande

|

| ... | |

|

Music

|

Richard Strauss

|

|---|---|

|

Text

|

Hugo von Hofmannsthal

|

|

Conductor

|

Jonathan Nott

|

|

Director

|

Ulrich Rasche

|

|

Sets

|

Ulrich Rasche

|

|

Lighting

|

Michael Bauer

|

|

Costumes

|

Sara Schwartz, Romy Springsguth

|

|

Chorus master

|

Alan Woodbridge

|

| ... | |

Video

The story

Mycenae, in the inner courtyard of the palace. Once upon a time, King Agamemnon was slain here in the bath by his wife (Clytemnestra) and her lover (Aegisthus) after his return from Troy. His daughters Electra and Chrysothemis have been held as prisoners ever since. Their brother Orestes is on the run. Uncertainty and panic reign. As she does every day, Electra enacts her ritual — she remembers her dead father: “Where are you, father?”. Blood vengeance is her goal. Her sister Chrysothemis appears with a warning: they want to lock Elektra away in the tower, to silence her for good. Now, Electra calls Chrysothemis to perform the deed: they must slay their mother and her lover with the axe that once smashed their father’s head. Chrysothemis does not seek revenge, she seeks a normal life: “I am a woman and want a woman’s destiny”, she wants to give birth and have children. Electra’s contempt puts an end to their exchange: “Why are you crying? Away! Inside!”

Unrest breaks out in the palace. The queen is plagued by nightmares. She seeks help from her “clever” child, Electra. Mother and daughter face each other painfully. Clytemnestra seeks a remedy to alleviate her nocturnal woes. Electra answers her: the appropriate blood sacrifice, performed by a man with an axe, could free her from her nightmares. She torments her mother with the threat of death and the hope of Orestes’ return. The mother withdraws, distraught.

News arrives that Orestes has been struck dead by his horses. The mother exults, Electra does not want to believe it, Chrysothemis breaks down in despair. Electra now wants to take revenge herself. She takes out the hidden axe. Suddenly a strange man stands before her, saying he is a companion of her dead brother. At first, the siblings do not recognise each other. But his shock at seeing Electra’s condition drives Orestes to reveal his identity. The floodgates of pain and rapture open as sister and brother recognize each other.

They agree on what must happen: “Those at whose bidding I have come, / The gods, they will be there to help me.” Orestes, accompanied by his guardian, enters the palace and kills his mother.

The court is thrown into turmoil. The returning Aegisthus is escorted into the palace by Electra with feigned courtesy. He too is slain by Orestes. Chrysothemis calls Electra back to the palace for the celebration. Electra is exhilarated about herself and her deeds: “I have sown the seeds of darkness and reap joy upon joy”. In a wild voice, she calls for a dance and like a maenad, she dances herself blissfully to death.

Insights

An interview with director Ulrich Rasche by dramaturg Stephan Müller

Stephan Müller: You have a reputation as a scenographer for building monumental machines for the performers to inhabit. For this you use huge theatrical turntables, lifting platforms and conveyor belts on which the performers walk and chant in rhythm (sometimes even attached with ropes). How did you use your directing principles for Elektra?

Ulrich Rasche: As in our work in spoken theatre, the singers will also move in this opera throughout this production on two rotating discs. The combination of speech, movement, space and light is central. In spoken theatre, we infer the movement of the steps from the rhythmic pattern of the text and the meaning attached to it. In opera, the music helps us to define the dynamics of the movements. Strauss himself studied the language of Hofmannsthal closely and transposed it into music. It is amazing how precisely he draws inspiration from the syntax of sentences and their spoken melody.

SM: The decor for Elektra is from the play staged in Munich. The space will be completed by an orbital platform that will pass around the central disc. Why did you make this extension?

UR: As in Munich, a tower stands centre stage in Geneva. This steel construction, covered with a perforated sheet, is transparent or opaque depending on the lighting. The tower constitutes the real space in which the three female protagonists of the opera seem to be caught in an endless spiral. As the discs continuously rotate, the characters turn incessantly in circles. Thanks to a very precise mechanical system of rotations, movement and lifting of the elements of the set, there are multitude of places and situations in which Electra, Chrysothemis and Clytemnestra settle their conflicts. Even if it seems at times that one character has a more dominant position over the others, thanks to specific configurations of the staging elements, all the characters are caught in the mechanism of the machine: no one can escape the curse of the home, the cycle of murder and revenge. The second disc built for Geneva is above all a place for servants and valets. This vertical axis highlights the hierarchies and dependencies within the system.

SM: The portrayal of women about a hundred years ago was different from that of our time. Performers today see Strauss/Hofmannsthal's Elektra as an expression of a ‘hidden contempt for women’. We infer patriarchy, a denigration of the feminine. In a radical interpretation, Elektra would be outright ‘put to death by music and offered to the public as a female victim’. I see the Strauss/Hofmannsthal project as one showing a deep complicity with Electra; the audience should identify with the title character.

UR: Our view of the characters in Elektra can be empathetic or more distantly exhilarating. In the first case, we feel involved with the characters. We suffer as they suffer. In the second case, we revel or even rejoice in the suffering of women exposed to their fate. Of course, we look today at the play with different eyes than those of a hundred years ago. Our reading is conditioned by the ideology of each era and by preconceived judgments. But I don't mean that Hofmannsthal nor Strauss indulged in a ‘misogynistic leaning’.

SM: There is also a breakdown in the political order in Elektra. After the murder of King Agamemnon, Mycenae begins to crumble. There is no succession to the throne or continuity of monarchical power. Aeschylus' Oresteia continues the Elektra story whereby a new political order emerges: democracy.

UR: In Oresteia, the consistent crises of the political order lead in the end to change. The two-headed system, with gods and an upper class that decide everything, dissolves and is replaced by the ‘government of the people’. The tenement of democracy is universal participation in the question of what is the right social order. It is important to me that we see a critique of political relations in our Elektra, a critique of the domination that destroys human beings. Today, we must preserve ‘the invention of democracy’ against all challenges - from right-wing populism, conspiracy theorists and other extreme ideologies.

Gallery