The Flying Dutchman

When the mysterious captain of a phantom ship is cast ashore in a storm, he tries to escape eternal damnation through the love of a faithful woman.

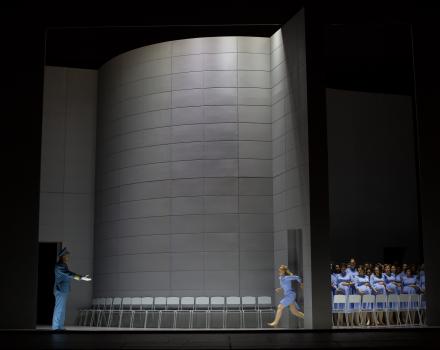

Wagner wrote his first great opera after a perilous escape from Riga. Latvian National Opera returns this otherworldly tale to its origins in a new production directed by Viestur Kairish.

Cast

|

The Dutchman

|

Egils Siliņš

|

|---|---|

|

Senta, Daland's daughter

|

Vida Miknevičiūtė

|

|

Daland, a Norwegian sea captain

|

Ain Anger

|

|

Erik, a huntsman

|

Corby Welch

|

|

Mary

|

Ilona Bagele

|

|

Steersman

|

Mihail Chulpaev

|

|

Chorus

|

Chorus of the Latvian National Opera

|

|

Orchestra

|

Orchestra of the Latvian National Opera

|

| ... | |

|

Music

|

Richard Wagner

|

|---|---|

|

Conductor

|

Mārtiņš Ozoliņš

|

|

Director

|

Viestur Kairish

|

|

Sets

|

Reinis Dzudzilo

|

|

Lighting

|

Oskars Pauliņš

|

|

Costumes

|

Krista Dzudzilo

|

|

Text

|

Richard Wagner

|

| ... | |

Video

The story

Act I

A storm has driven the sea captain Daland's ship ashore. The voyage has exhausted the crew and soon they all go to rest. The Steersman tries to keep up his spirits with a song but falls asleep on the watch. Suddenly a strange vessel pulls alongside Daland's ship. Its captain is the Flying Dutchman, who has been condemned to eternal wandering unimpeded by storms or pirates. Once in seven years he is permitted to land. The Dutchman offers Daland unheard-of wealth, pleading in return for lodging and the hand of his daughter, Senta. Daland accepts the Dutchman's proposal, and the ships set sail.

Act II

Waiting for the return of Daland's ship, the girls are working on their spinning wheels and singing. Senta's friends tease her about the huntsman Erik, her ardent suitor. Senta, heedless of facetious remarks, sings a ballad about the Flying Dutchman, which she came to love already in childhood, and discloses her innermost secret: with a faithful love she wishes to save the harried seaman. Senta's words surprise Erik, who is overtaken by a strange foreboding. He relates a dream in which he saw her embrace the mysterious captain. The Dutchman and Senta's father appear, and the father announces the marriage arrangement. Senta is transfixed by the Dutchman. The Dutchman does not turn his eyes from Senta, hoping that her love and faithfulness will lift his curse.

Act III

Sailors celebrate their safe return to land. They call out to the Dutchman's ship, inviting the crew to join them, but the ship remains dark and silent. Daland's sailors deride the mysterious crew and their captain. A storm rises and apparitions approach the shore over the waves, and with that the invited guests have arrived.

Erik tries to dissuade Senta from binding her life with the eerie stranger. Senta is unwilling to listen to him, for she has made an oath and is called by a supreme mission. Erik then reminds her of his love for her. The Dutchman, seeing Senta together with Erik, is stricken by desperate jealousy and a sense of loss, believing that Senta, too, has failed to render him undying faithfulness. He reveals his secret and sets off towards his ship to continue this endless roaming prescribed by the curse. Senta throws herself into the sea from the top of a cliff thus redeeming the Dutchman's sins with her death. The Flying Dutchman's ship disintegrates against the cliffs, and his odyssey comes to an end.

Insights

5 things to know about The Flying Dutchman

1° A stormy prelude

Richard Wagner married the German actress Wilhelmine ‘Minna’ Planer in the winter of 1836. Their relationship was tempestuous, with the jealous and possessive composer’s outbursts frequently leaving Minna in tears. The actress also struggled to deal with her husband’s debts and threats from his creditors. Within six months, she left him for another man.

To escape the fiasco, Wagner moved to Riga (then in the Russian Empire), where the 26-year-old became music director of the Court Theatre and engaged Minna’s sister as a singer. Wagner’s wife eventually decided to join him in Riga, but their lifestyle was lavish beyond their means and led to more unpayable debts. The couple planned to run from their creditors but, having suspected such a plan, the authorities confiscated their passports.

Undeterred despite the risk of being shot by border guards, they crossed illegally into Prussia. They then took a wagon to the coast but it overturned en route, crushing Minna and causing her to miscarriage. They finally made it to the port of Pillau (now Baltiysk in Kaliningrad) and set sail for London on board the ship Thetis, which ran into a storm and was forced to berth in a Norwegian fjord. The weather and the shoreline made an impression on Wagner’s imagination, and he asked the sailors about the legend of the Flying Dutchman. After a terrifying 24-day journey for a trip that should have taken eight, Wagner arrived safely in London with his wife by his side and his next opera in his head.

2° A ghostly ship

The myth of a phantom ship doomed to sail the oceans forever is likely to have originated from the golden age of the Dutch East India Company in the 17th century. The first print reference appeared in John MacDonald’s 1790 travelogue Travels in various parts of Europe, Asia and Africa during a series of thirty years an upward, in which sailors see the Flying Dutchman during a storm. Over the next half-century several stories inspired by the legend appeared in print, including ‘Vanderdecken’s Message Home’ and Samuel Taylor Coleridge’s 'The Rime of the Ancient Mariner'.

Heinrich Heine’s satirical novel Aus den Memoiren des Herrn von Schnabelewopski (‘The Memoirs of Mister von Schnabelewopski’) was the first to introduce the cursed captain setting foot on land every seven years with the chance to be saved through the devotion of a faithful wife. Heine presented this redemptive power of love as a means for ironic humour, but when Wagner wrote his libretto for The Flying Dutchman (Der fliegende Holländer) he took the theme literally and seriously. The myth of the Flying Dutchman has since been retold in countless adaptations, such as the 2006 Disney film Pirates of the Caribbean: Dead Man’s Chest.

3° Navigating the choppy waters of life

‘The most universal trait of mankind,’ said Wagner in connection to the Flying Dutchman myth, ‘is the longing for calm amidst life’s storms’. He saw the Dutchman as symbolising the eternal search for solace and salvation from the rough waves and weather of life. That is why he reminded conductors and directors not to neglect the sea itself in their productions of The Flying Dutchman: ‘the sea between the headlands must be seen to rage and foam as much as possible; the representation of the ship cannot be too naturalistic: little touches, such as the heaving of the ship when struck by an exceptionally strong wave, must be very clearly portrayed. The constant subtle changes in lighting demand especial care.’

4° Three romantic operas

The premiere of The Flying Dutchman in early 1843 marked the start of Wagner’s career as a mature opera composer. He had already completed three operas, namely Die Feen, Das Liebesverbot and Rienzi, but he dismissed these as apprentice works and would later reject them from his oeuvre. Indeed, in his essay ‘Eine Mittheilung an meine Freunde’ (‘A Communication to My Friends’), he identified the opera and its libretto as representing a new start for him: ‘From here begins my career as poet, and farewell to the mere concocter of opera-texts.’

The Flying Dutchman and his following two operas, Tannhäuser and Lohengrin, are commonly referred to collectively as Wagner’s ‘romantic operas’, and they display a significant advance in his handling of themes, orchestration and character development. They are the earliest works to have entered the so-called ‘Bayreuth canon’, the set of Wagner’s operas that form the core repertoire of the famous Franconian festival.

The three ‘romantic operas’ brought the composer renown and success, but they are not regarded as his masterpieces; that title is given to his ‘music dramas’ that came later, namely Der Ring des Nibelungen, Tristan und Isolde, Die Meistersinger von Nürnberg and Parsifal, in which Wagner broke new harmonic ground and strove to fuse all musical, poetic and dramatic elements into one unified artistic whole.

5° Returning to Riga

Fleeing the difficulties of his time in Riga and sailing off on a risky sea voyage gave Wagner not only an idea for a new opera, but also a place in Latvian and musical folklore. ‘Fleeing Riga by boat, he became stuck in time. This ship, forever stuck in this mythical time, has once again stopped where it started.’ says director Viestur Kairish, who was born in the Latvian capital. The Flying Dutchman is a work that blurs the boundary between the mythical and the real, a boundary that he has explored and embraced in Latvian National Opera’s new production. ‘Time and space – Riga. Maybe it’s the wreck of a ship washed up on some lonely beach; maybe it’s an aeroplane that has crashed in the desert. What’s important is that the Dutchman has returned to the city where Wagner went from Kapellmeister to composer.’

Gallery