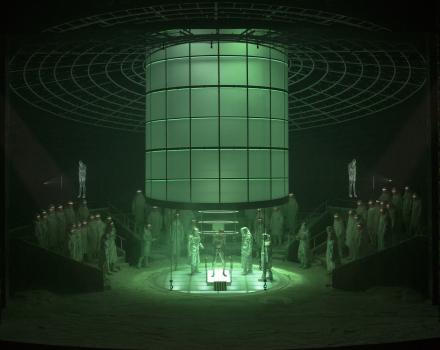

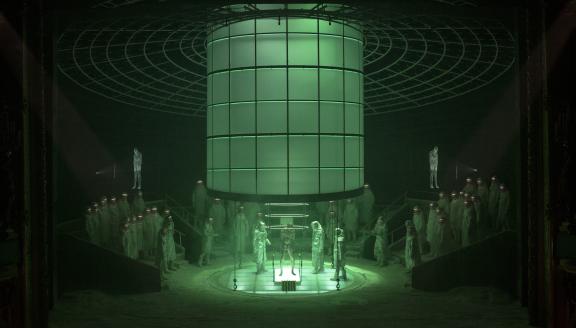

Scientists discover a creature frozen into the ice fields of the North Pole. As it is gradually brought back to life in a bold experiment, the creature experiences flashbacks of its painful past with its creator.

Two hundred years after its publication, American composer Mark Grey takes Mary Shelley’s groundbreaking science fiction novel as the basis for his first full-length opera. Directed by Àlex Ollé of the theatrical group La Fura dels Baus, this modern interpretation warns of the growing gulf between our capacity to invent and our inability to comprehend.

Cast

|

Victor Frankenstein

|

Scott Hendricks

|

|---|---|

|

Creature

|

Topi Lehtipuu

|

|

Elizabeth

|

Eleonore Marguerre

|

|

Dr. Walton / Prosecutor

|

Andrew Schroeder

|

|

Henry

|

Christopher Gillett

|

|

Blind Man / Father

|

Stephan Loges

|

|

Justine

|

Hendrickje Van Kerckhove

|

|

Chorus

|

La Monnaie Chorus

|

|

Orchestra

|

La Monnaie Symphony Orchestra

|

| ... | |

|

Music

|

Mark Grey

|

|---|---|

|

Conductor

|

Bassem Akiki

|

|

Director

|

Álex Ollé (La Fura Dels Baus)

|

|

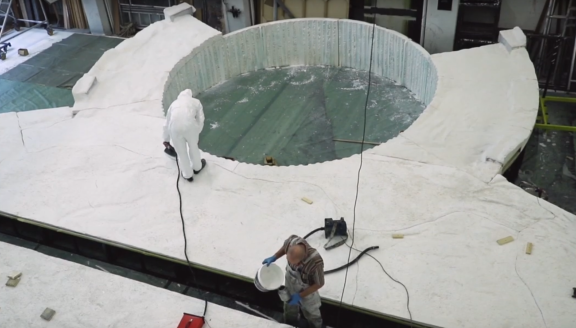

Sets

|

Alfons Flores

|

|

Lighting

|

Urs Schönebaum

|

|

Costumes

|

Lluc Castells

|

|

Text

|

Júlia Canosa i Serra

|

|

Chorus master

|

Martino Faggiani

|

|

Video director (stage)

|

Franc Aleu

|

|

Video directors (streaming)

|

Anaïs and Olivier Spiro

|

| ... | |

Video

The story

Act I

In the year 354 of the New Anthropogenic Glacial Period, members of an expedition led by Dr Walton discover a strange creature trapped in the ice. While his resuscitation is being performed, Walton examines it and wonders about the possibility of penetrating its memory and materializing its memories. The Creature comes back to life and stutters. Its stammering takes it back to the late 1810s, to Victor Frankenstein, who shaped this repulsive creature and brought it to life. Victor is called by Elizabeth, his beloved, and joins her. Together, they swear to love each other forever, while the Creature, hidden, watches them.

Villagers discover the existence of the hideous creature and are terrorised by it. They attack it and chase it away, without Victor and Elizabeth noticing. The Creature wanders into nature. It tastes a form of freedom and learns through its observations. It is particularly studying a blind old man and his family, whom it watches from a distance and so learns how to think and speak. The Blind Man gets to know the Creature. He cannot see it but he enjoys its company. He tells it that beings are naturally good and that the Creature should channel its aggression to rise to the rank of man. Felix, the Blind Man’s son, suddenly bursts in and, thinking he’s defending his father, violently attacks the Creature, who flees.

The Creature looks on as William, Victor Frankenstein's younger brother, plays in the wild with Justine, a family servant. Justine loses sight of the child. William then finds himself facing the Creature and his own death. In court, Justine is charged with William's murder and faces a hurl of insults from the assembled crowd. Elizabeth defends her, but there is evidence against Justine, not least the fact that she was holding the necklace that William was wearing. The Creature confesses to Victor of being responsible for William's death, but Victor remains silent during the trial and Justine is sentenced to death.

Act II

The scientists assembled around the Creature wish to suspend their exploration of the monster's memories. But Walton insists on continuing the experiment, for the Creature’s past stories shed light on their own present, and perhaps by reliving its traumas it will be able to find peace. Back in the Creature's memory, it has kidnaped Victor Frankenstein in a glacial cave. It argues that its cruelty is only the consequence of the suffering it has been inflicted. It begs Victor, its creator, to live up to the responsibility he bears towards the Creature by creating an alter ego with whom it share its life.

Elizabeth writes a letter to Victor: she misses him and cannot understand his silence. Henry Clerval is trying to get Victor, his friend, out of his laboratory. Victor is there busily creating a woman for the monster but then changes his mind and destroys his work in progress. The Creature takes Henry hostage to blackmail Victor: if he does not continue the work on its companion, then his friend will die. Faced with Frankenstein's refusal, the Creature slits Henry's throat and threatens to attack Elizabeth.

In conversation with Walton, the Creature says: ‘My heart was made to feel love and sympathy; but suffering turned it towards vice and hatred.’ Walton encourages it to forgive Victor for his arrogance, and thus to build another future, free from the memories of past violence. On her wedding bed, Elizabeth hears a gloomy song that frightens her: it’s the Creature approaching. When Elizabeth sees the Creature, she realizes that it is what Victor has been hiding from her. She does not reject it and, knowing that they are both condemned, shows it affection. The Creature attacks Elizabeth and kills her, then breaks into tears. Victor discovers Elizabeth's lifeless body and already knows that the Creature is the perpetrator of the murder. He curses this creation that was supposed to elevate him above all men but that has cast him down to beneath the earth.

Finale

The Creature pities Frankenstein, whom it nevertheless recognised as her father. Walton assures the Creature that all its memories have shaped its identity, and that it is therefore truly human. But the Creature, thus fully exercising its free will, refuses the company of the scientists and decides to sacrifice itself.

Insights

1° A modern Prometheus

The idea of creating an opera to mark the two-hundredth anniversary of Mary Shelley’s novel Frankenstein; or The Modern Prometheus came up in a conversation between that Spanish director and co-founder of the artistic collective La Fura dels Baus, Àlex Ollé, and the director of La Monnaie / De Munt, Peter de Caluwe. This very first science-fiction novel was published in 1818, two years after Shelley hit upon the idea for it while staying with Lord Byron near Lake Geneva. Interpellated by the technological and scientific developments of her time and their unforeseeable consequences for man and society, she wrote her own ‘what if’ scenario. And, as in all good science fiction, that scenario goes beyond futuristic speculative fiction. Frankenstein touches on essential philosophical and ethical questions which, transposed to the present day, apply equally to creative experiments in biotechnology, genetics, information science and medicine.

2° Bolts and stitches

The successful 1931 Hollywood adaptation of Frankenstein starring Boris Karloff borrowed the sets and costumes from the Dracula filming of the same year, thus searing into the collective memory forever the image of a lethargic monster brought to life by a mad scientist in a Gothic castle. Since Karloff's portrayal, the creature almost always appears in popular culture as a towering, undead-like figure, often with a flat-topped angular head connected to his body by stitches and with bolts on his neck to serve as electrodes. But in their twenty-first century opera, Mark Grey and Àlex Ollé are returning to the source, which they see as highly topical. At a time of atom bombs, genetic engineering, artificial bio-selection and social media, the gap between our ability to invent and our inability to understand could be even greater than in Shelley’s time. The need is greater than ever to experience a moral and emotional awareness in parallel with what we have just created.

3° In cold storage

Grey and Ollé asked librettist Júlia Canosa i Serra to turn the novel into a stage play and to update Shelley’s poetic English. The opera Frankenstein is set in an unspecified future. Several scientists discover a creature frozen into the ice fields of the North Pole. One of them, Dr Walton, takes the lead in bringing him back to life in a bold experiment. Gradually the ‘Creature’ returns to consciousness. Snatches from a murky past surface and, with the help of high-tech equipment, the scientists also succeed in visualising those mental images. The crucial scenes from what took place so many years ago (in Mary Shelley’s novel) manifest themselves in flashbacks. At the centre is the relationship triangle between Victor, Elizabeth and the Creature, which becomes strained through Victor’s commitment to his wife - a romance that will always be denied his creation.

4° Back in Brussels

For the American composer and sound designer Mark Grey, the world premiere of his first full-length opera at La Monnaie / De Munt is something of a homecoming. Back in 1991 he worked in Brussels as the right-hand man of fellow countryman John Adams on the creation of the latter’s opera The Death of Klinghoffer. Grey’s musical writing is based on a very inventive ‘recomposition’ of diverse musical material: old or romantic music, industrial noise, electro-acoustic sounds, and the harmonic language of John Adams and Aaron Copland. When combined together, these different elements produce powerfully emotional music in which moments of intense energy are interspersed with calm meditation.

5° American beauty

Though as yet less well‐known in Europe, on the other side of the Atlantic, Mark Grey can pride himself on an impressive track record, initially as sound designer for artists like Adams, Steve Reich and Philip Glass but, since his debut with the Kronos Quartet at Carnegie Hall, also as a composer. In 2007-08 he was composer-in-residence with the Phoenix Symphony, where he composed his first large-scale work, Enemy Slayer; A Navajo Oratorio for baritone, 130 singers and orchestra. The soloist at the premiere was Scott Hendricks, who has since developed a strong bond with Grey. Having recently performed at La Monnaie / De Munt as Barnaba in La Gioconda, Tonio in Pagliacci and in the title role of Macbeth, the American baritone now returns to the Brussels theatre to create the role of Victor Frankenstein in this new opera.

Gallery