Having led a series of victorious campaigns against rival territories, a warrior wins the hand of a Brahmin priestess. But when his true caste is brought to light, he risks losing more than just his bride.

Based on a play by Casimir Delavigne, Stanisław Moniuszko's final opera is rarely performed. Poznań Opera presents it in this new production directed by Graham Vick to celebrate the 200th anniversary of the composer's birth.

Cast

|

Idamor

|

Dominik Sutowicz

|

|---|---|

|

Ratef

|

Pavlo Tolstoy

|

|

Akebar

|

Szymon Kobyliński

|

|

Neala

|

Monika Mych-Nowicka

|

|

Dżares

|

Mikołaj Zalasiński

|

|

Priestess

|

Aleksandra Pokora

|

| ... | |

|

Music

|

Stanisław Moniuszko

|

|---|---|

|

Conductor

|

Gabriel Chmura

|

|

Director

|

Graham Vick

|

|

Sets

|

Samal Blak

|

|

Lighting

|

Giuseppe di Iorio

|

|

Costumes

|

Samal Blak

|

|

Text

|

Jan Chęciński

|

|

Chorus master

|

Mariusz Otto

|

| ... | |

Video

Prologue

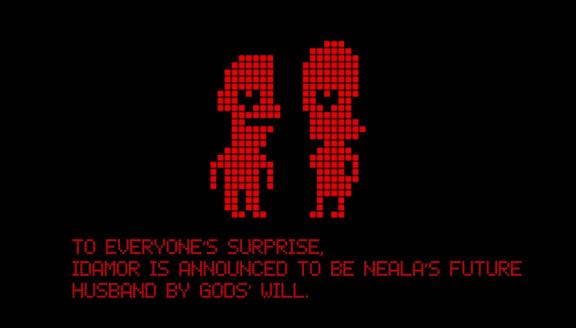

Idamore, a brave chief who has only recently won a war, confides in his friend Ratef. Idamore is in love with the priestess Neala, daughter of the High Priest Akebar. The secret conversation between the friends is interrupted by a sudden uproar: a pariah has entered the area of the sacred grove. He has broken the law – no ‘untouchable’ person can ever enter it – and his penalty for such an act is death. The angry crowd chases the pariah while Idamore alone stands in his defence.

Act I

Neala also loves Idamore but they both know that their feelings are at odds with the rules of the caste system. The High Priest Akebar gathers the priests in the temple. He warns them that the warrior caste is gaining more and more support among the people and wants to deprive the priests of their power. Akebar is aware of Neala's feelings, so he offers his daughter's hand to Idamore, releasing her from her priestly vows. This cunning move is intended to alleviate the growing conflict between the priests and the warriors.

Act II

Akebar calls Idamore his ‘son’. The word brings back painful memories for Idamore, who has a secret: he too is a pariah. For years he has been living in hiding, fearing that someone would recognise him as an ‘untouchable’. He had renounced his father and his origins but now, plagued by remorse, he confesses his secret to Neala. She decides to stay with her beloved until death.

Ratef announces that an old man, Dżares, has appeared in the city asking about Idamore. Neala decides to welcome the poor pilgrim and see what he wants. He insists on seeing Idamore, who recognises the old man as his long-lost father. Dżares urges his son to return to his homeland but Idamore's love for Neala makes that impossible for him.

Act III

Akebar leads Idamore inside as the wedding ceremony begins. Dżares breaks free from the crowd, accusing Idamore of hypocrisy. The participants of the ceremony feel sorry for the rejected old man, who, in a surge of grief, confesses to being a pariah. Akebar orders him to be killed but Idamore stands in defence of his father. In a fit of anger, he also admits to being a pariah and is instantly killed by Akebar. When Neala comprehends what has happened, she announces that from now on she is Dżares's daughter. To satisfy the people’s anger, Akebar banishes his daughter from her homeland.

Insights

5 things to know about Paria

1. A provocative play

Casimir Delavigne was a French poet and dramatist. He gained royal favour early in life when he obtained a sinecure for writing a dithyramb celebrating the birth of Napoleon II. Fame followed soon after when, inspired by the Battle of Waterloo, he wrote three stirring poems that echoed in the hearts of the French people. Twenty-five thousand copies were sold and Delavigne was appointed the honorary librarian of the Chancery, with no duties to discharge. When he then turned his pen towards plays, he was equally warmly received. First came the five-act tragedy Les Vêpres siciliennes, then the short comedy Les Comédiens, and thirdly, Le Paria, which was staged in 1821. With its freely-expressed criticism of social hierarchy and the establishment - albeit in India - it became a popular success. But it also incurred the displeasure of the king, who stripped Delavigne of his librarianship.

2. Italian opera adaptations

The French play caught the attention of Michele Carafa, the son of an Italian duke. As a young man, he had studied composition under Luigi Cherubini - composer of Medea - and later went against the wishes of his father by quitting his military career and moving to Paris to pursue a new career as an opera composer. Gaetano Rossi adapted Delavigne’s play into a libretto, and in 1826, Carafa’s tragic melodrama Il paria opened at the Teatro La Fenice in Venice. This in turn piqued the interest of Gaetano Donizetti, who asked Domenico Gilardoni to write a new libretto based on Delavigne and Rossi’s texts. The composer completed his own Il paria in the winter of 1828, and it was first performed in 1829 at the Teatro San Carlo in Naples. With six performances, the opera was deemed a modest success; the American musicologist William Ashbrook identified it as Donizetti’s finest achievement up to that point.

3. A long-time fascination

Although Gilardoni’s libretto had been published, Donizetti’s score remained only in manuscript form. It is therefore highly doubtful that Stanisław Moniuszko would have known the music when he started work on his own opera adaptation of Le Paria in 1859. The Polish opera historian Piotr Urbański admits that he cannot fully explain Moniuszko’s long-time fascination with Delavigne’s play, but that it started when the composer first read and tried to translate the tragedy at the age of seventeen. ‘The spirit of the Enlightenment is visible in the harsh criticism of religion and its institutions, brought to the foreground in the play,’ explains Urbański. ‘One might wonder how often, while he was reading the play, the young composer’s thoughts went to the successful fight for independence being waged at the time by the Greeks, and later, when composing the opera, to the subsequent uprisings and revolutions he had witnessed throughout his life.’

4. New instruments for a new setting

During his life, Moniuszko was recognised as an important Polish composer, and today, like Glinka in Russia, Erkel in Hungary and Smetana in the Czech Republic, he has become associated with the concept of a national style in opera. His most popular operas - Halka, Hrabina and The Haunted Manor - are all set in Poland, and the source of his melodies and rhythmic patterns often lies in dances such as the polonaise, mazurka, kujawiak and krakowiak. Writing an opera set in India was therefore a departure from the norm. Moniuszko expanded the orchestra to include a tam-tam, gong, contrabassoon and bass clarinet. Harmonically and instrumentally, Paria is one of the composer’s most colourful works. Deserving of particular praise is the overture, which, in the words of British critic Andrew Clements, ‘ends in a blaze of almost Straussian grandeur’, and which is regarded by many to be Moniuszko’s best piece of orchestral writing. He and his librettist, Jan Chęciński, worked on the opera on and off for a decade, until it finally received its premiere at Polish National Opera in 1869. But after only seven performances, and despite relatively positive reviews in the Warsaw press, it was removed from the repertoire. This caused much distress for the composer, who, until his death three years later, could not understand why his compatriots were uninterested in his final opera.

5. Solving the mystery

Paria is by far his most mysterious piece of work. Mysterious, as after its short-lived first run in Warsaw, it languished in obscurity for several decades. It rarely draws the attention of scholars and is largely unknown even within the opera world. It has been produced less than a dozen times in its history, all but one of them in Poland; and there has only been one complete recording, which was conducted by Warcisław Kunc at Castle Opera in Szczecin and released on the DUX record label in 2008. As part of the 2019 Year of Stanisław Moniuszko to celebrate the bicentenary of the composer’s birth, Poznań Opera House is proud to present Paria to the world in this innovative new production. Directed by Graham Vick and performed in the city’s huge sports and entertainment arena, it places the audience at the heart of the action, eliciting their active engagement with the performance. ‘Mingle with the crowd of actors, eavesdrop on the orchestra, sneak a peek at the conductor, and feel that High C vibrating,’ says Poznań Opera House. ‘Become a part of the revolution!’

Gallery