A beautiful, coldhearted Chinese princess has issued a decree for her suitors: whoever cannot solve her riddles to win her hand will be beheaded. When a mysterious man passes her test, will she finally open her heart to love?

Puccini’s last opera Turandot, unfinished at his death, is musically his most adventurous work. Infused with Asian touches, it cannot deny its Italian heritage, culminating in the world-famous aria ‘Nessun dorma’. In 2017, the director duo Ricci/Forte were awarded the prestigious Italian Music Critics Award Franco Abbiati for best direction for their creative project.

Cast

Turandot | Rebeka Lokar |

|---|---|

Calaf | Renzo Zulian |

Liu | Valentina Fijačko Kobić |

Timur | Berislav Puškarić |

Altoum | Božimir Lovrić |

Ping | Davor Radić |

Pang | Mario Filipović |

Pong | Ivo Gamulin |

Mandarin | Neven Paleček |

Performers | Matino Antunović, Marko Brkljačić, Andrej Drenski, Mario Grdanjski, Svebor Kamenski-Bačun, Piersten Leirom, Domagoj Modrušan, Lorenzo Raušević, Kristian Šupe, Karlo Žganec |

Chorus | Choir of the Croatian National Theatre in Zagreb |

Orchestra | Orchestra of the Croatian National Theatre in Zagreb |

| ... | |

Music | Giacomo Puccini |

|---|---|

Creative project | Ricci/Forte |

Director | Stefano Ricci |

Conductor | Marcello Mottadelli |

Set and light designer | Nicolas Bovey |

Costume designer | Gianluca Sbicca |

Coreographer | Marta Bevilacqua |

Orchestra director assistants | Darijan Ivezić, Ivan Josip Skender |

Stage director’s assistant | Liliana Laera |

Set designer’s assistant | Eleonora De Leo |

Costume designer’s assistants | Rossana Gea Cavallo, Antonia Jakšić Dorotić |

Choir master | Luka Vukšić |

Libretto translation | Dubravka Oršić |

Children’s choir master | Dijana Rogulja Deltin |

| ... | |

Video

The story

Act I

The walls of the great purple City.

Peking, legendary times. A bustling crowd in front of the walls of the imperial City. A Mandarin is again reading out Princess Turandot’s proclamation declaring she will marry the prince who succeeds in solving her three riddles, but whoever accepts the challenge and mistakes the replies will be beheaded as the moon rises. This is what is about to happen to the latest pretender, the Prince of Persia. In the throng a blind old man is trampled: Calaf rushes to assist him and recognises his father, the deposed Tartar king, Timur. The old king believed his son had died in battle: now he has lost everything; only the slave Liu has stayed with him. The girl confesses that she had helped the king because one day, in the palace, Calaf had smiled at her.

The excited crowd invokes the rising of the moon and calls for the executioner, but when the Prince of Persia is led forwards its mood changes – moved by his tender age and noble bearing – and instead it implores pardon for the young man. Turandot makes a sign ordering his execution. Struck by the fleeting glimpse of the icy Princess, Calaf decides to tackle the three riddles. Ping, Pong and Pang, Turandot’s three ministers, attempt to persuade him that Turandot is after all only a woman and that there are many others he could have without risking his life in vain. Liu asks what will become of her and Timur if he were to die, but Calaf is deaf to her supplications and, calling out Turandot’s name, announces he will accept the challenge and sounds the ritual gong.

Act II

A pavillon.

Ping, Pong and Pang let their frustration show. They are tired of a routine of unsolved riddles and decapitated heads and hope that Turandot will finally find a husband so they can retire. But, alas, preparations must be made for the new pretender’s attempt.

Square in front of the palace.

While the crowd gathers, the sages arrive bearing the rolls with the answers to the riddles. Turandot’s father, the elderly Emperor Altoum, invites Calaf in vain to desist. Finally Turandot appears. The beautiful princess relates how she dreamt up the game of riddles to revenge Lo-u-Ling, an ancestor of hers who, thousands of years ago, had been raped and killed by a foreign king. For this reason she hates men. Turandot is sure that no one will be able to solve the riddles and thus possess her, and wholeheartedly believes that the young prince is destined to the gallows. But Calaf does not give up, and one by one succeeds in resolving the riddles posed.

Devastated, Turandot asks her father not to relinquish her to the foreign prince but Altoum reminds her she is bound by oath. Boldly, Calaf proposes that she should successfully answer a riddle in her turn: if Turandot can find out his real name before the sun rises he will gladly die, otherwise the princess must marry him. Disconsolate, the old emperor hopes the young man will be able to marry Turandot and thus become his son.

Act III

Garden of the palace.

During the night, the heralds proclaim Turandot’s orders: no one in the city must sleep and every attempt must be made to discover the foreign prince’s identity. Calaf anxiously awaits the coming of dawn and looks forward to the moment when the sun will rise and he will be able to embrace Turandot. Ping Pong and Pang offer him immense riches and the most beautiful women in an attempt to make him renounce the princess, but Calaf rejects every enticement.

A little while later a group of the princess’s guards arrives dragging Liu and Timur with them: the two have been seen in the prince’s company and probably know his identity. Turandot arrives too. Under torture, Liu confesses that she knows the prince’s name but has no intention of revealing it. For love of the prince, she wants to grant him, with her silence, Turandot’s hand, who in her turn can do nothing but love him. So she snatches one of the guard’s daggers and kills herself, thus carrying her secret to the grave. In desperation, Timur clasps Liu’s hand as she is borne away, accompanied by the much moved crowd.

Insights

Not your typical fairytale princess

The story of Turandot originated in a French fairy tale collection by François Pétis de la Croix called Les mille et un jours (‘The thousand and one days’, not to be confused with the more famous One thousand and one nights). As many of these stories have only been found in de la Croix’s version, numerous scholars wondered whether he had made them up himself. In the case of Turandot, however, the origin seems to lie in a 12th-century story by the Azerbaijani poet and philosopher Nizami Ganjavi, ‘Seven Beauties’.

Puccini discovered the tale through Schiller’s play, which derived from the German version of an Italian commedia dell'arte by Carlo Gozzi, who in turn took the story from the de la Croix. What a detour! Puccini was not the first composer to take an interest in this colourful tale. Antonio Bazzini wrote Turanda in 1867, Ferruccio Busoni Turandot in 1917 only a few years before Puccini began his version.

‘Here the maestro put down his pen’

If Puccini was always known as meticulous, the writing of Turandot was particularly strenuous. In the four years before his death, Puccini was indecisive over the number of acts and specifically obsessed over the final love duet. In his eyes, it should become the all-important culmination of the opera. ‘I have placed, in this opera, all my soul,’ he wrote to a friend in March 1924. He died in November of that year.

After Puccini’s death, his friend Arturo Toscanini, who would conduct the premiere, suggested that the young composer Franco Alfano should finish the score. Although Alfano had Puccini’s sketches at his disposal, much of them were hard to interpret. Of the love duet, for instance, Puccini wrote puzzlingly ‘Then Tristan…’, in reference to Wagner’s opera which ends with Isolde exalted Liebestod (love death).

Turandot premiered at La Scala in Milan in April 1926. Famously, when the opera reached the last note written by Puccini, Toscanini ended the performance, saying something to the lines of ‘Here the Maestro put down his pen’. The Alfano version was only presented the following night.

A darkly enchanted world

Ricci/Forte’s production also follows Alfano’s ending. ‘After the first reading, we thought that the opera should end with Liu's death. But later we realized that the emotional trajectory seeks a happy ending. After all, we have enough disappointments and sad ends in real life‘, explains Stefano Ricci, who forms the duo Ricci/Forte with Gianni Forte, known for their experimental, sometimes provocative staging which could be seen on OperaVision with Nabucco. For them, the opera takes place in an enchanted world: ‘everything happens in Turandot's head, like a vision that allows her to make the characters act as she pleases’.

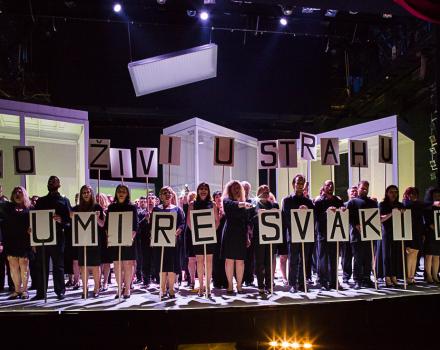

Twelve dancers representing her toys - shadows of past failed relationships - are on stage all the time with Turandot. Rebeka Lokar, who sings the title role, says of her character ‘Turandot is a young, intelligent girl. She’s not a typical fairytale princess, but she’s not a witch either. She is a young girl full of fears, because of which she pushes people away from her.’

‘Our main goal was to convey the fiction of a fairy tale,’ Forte points out. ‘Turandot is actually the director of this opera. She is a person who pulls the strings on her dolls, introduces us all to her world, which is actually the world of her imagination, but the only one in which she feels safe,’ explains Ricci. No chinoiserie, no orientalism can be found in this production.

‘Puccini loved the East very much and on one occasion he was at an Eastern dinner. There was a music box playing three tunes. Puccini takes the number three as a magic number from fairy tales. Turandot has three assistants, Ping, Pang and Pong, there are three puzzles that Calaf needs to solve, there are three acts.’, adds the conductor Marcello Motadelli. ‘For Puccini, the theatre was like that magical music box, like a fairy tale where anything is possible.’

Gallery