Turandot

Puccini’s last opera is all about riddles. The Emperor of China rules over the Forbidden City of Peking. His unmarried daughter, the Princess Turandot, has refused her hand to all her princely suitors by putting them to a test. She sets them three riddles; if they do not answer them correctly, they will lose their heads. As unlucky suitors fail and fall, up steps Calaf, a prince of the Tatar people.

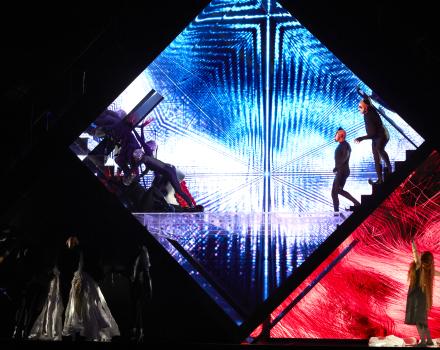

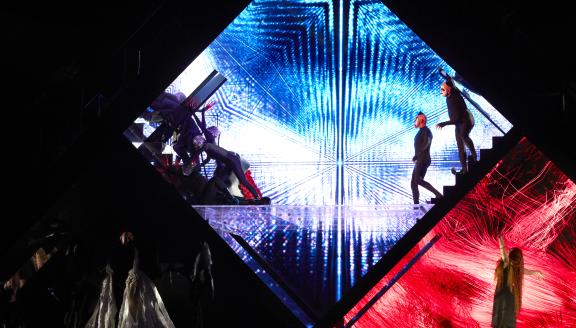

Daniel Kramer’s new staging in Geneva transposes the old fairy tale to a futuristic world where Turandot’s magic holds sway. In a dystopian game show, reminiscent of Hunger Games, the Princess presides over a surveillance state in which men are culled and the reproduction of the human race is conducted in breeding labs. For the first time in their career, the international art collective teamLab work extensively on the scenography of an opera, using state-of-the-art visual technologies never before seen on an opera stage. teamLab’s light creations are an immersive artistic experience known for their power to absorb and enthral audiences. Antonino Fogliani, a master of the Italian repertoire, conducts an excellent cast including Ingela Brimberg who returns to Geneva as the icy Princess Turandot, after taking the title role in Elektra - a performance also enjoyed by OperaVision viewers.

CAST

|

Turandot

|

Ingela Brimberg

|

|---|---|

|

Altoum

|

Chris Merritt

|

|

Timur

|

Liang Li

|

|

Calaf

|

Teodor Ilincai

|

|

Liù

|

Francesca Dotto

|

|

Ping

|

Simone Del Savio

|

|

Pang

|

Sam Furness

|

|

Pong

|

Julien Henric

|

|

A Mandarin

|

Michael Mofidian

|

|

Chorus

|

Grand Théâtre de Genève Chorus

Maîtrise du Conservatoire populaire

|

|

Orchestra

|

Orchestre de la Suisse Romande

|

| ... | |

|

Music

|

Giacomo Puccini

|

|---|---|

|

Text

|

Giuseppe Adami, Renato Simoni

|

|

Conductor

|

Antonino Fogliani

|

|

Director

|

Daniel Kramer

|

|

Scenography/Digital and Light Art

|

teamLab

|

|

Stage Design

|

teamLab Architects

|

|

Costumes

|

Kimie Nakano

|

|

Lighting

|

Simon Trottet

|

|

Choreographer

|

Tim Claydon

|

|

Dramaturgy

|

Stephan Müller

|

|

Choir director

|

Alan Woodbridge

|

| ... | |

Videos

The story

ACT 1

Turandot, daughter to the Emperor, has decreed she will only marry a Suitor who solves her Three Riddles. If the Suitor fails — off with his head! The Prince of Persia has just failed; the court prepare him for sacrifice; the gladiators pump the crowd; the crowd roars for blood. An old blind man is trampled in their hysteria. His faithful caretaker, Liù, pleads for help. A young man, Calaf, leaps to the elder, only to discover Timur, his long lost — and exiled — Father. The main event arrives: Turandot descends and beheads her failed Suitor. Calaf’s first glimpse of Turandot magnetizes him: he must have her. When the spectacle ends and the crowd clears, Timur and Liù try to convince Calaf to flee with them. But Calaf is crazy in love with the idea of Turandot. None will stop him. Turandot’s Three Ministers, Ping, Pang and Pong — the three Eunuchs who run this too-long-running show of riddles and blood-games — try to dissuade Calaf from pursuing Turandot. But their intended efforts only heighten Calaf’s will to win.

ACT 2

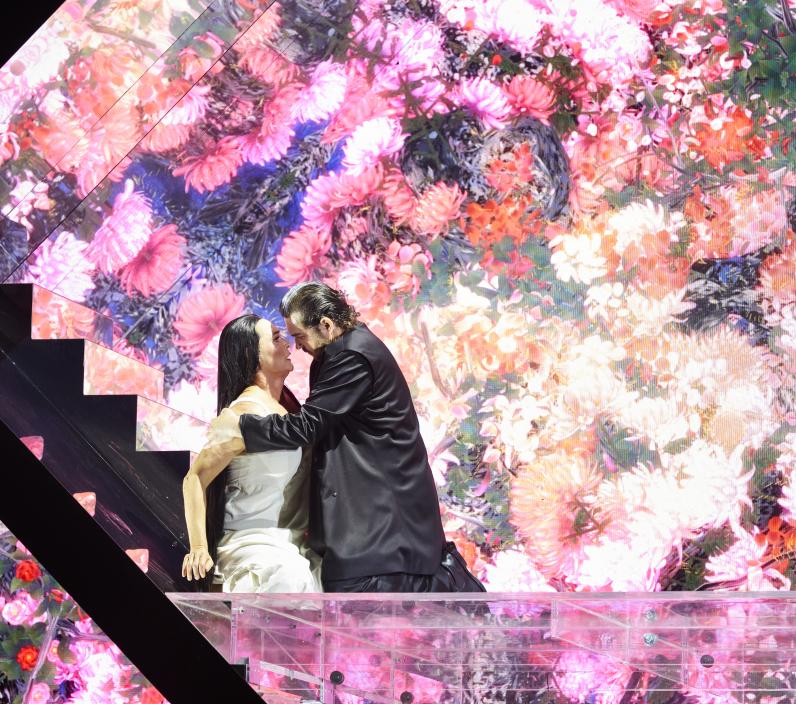

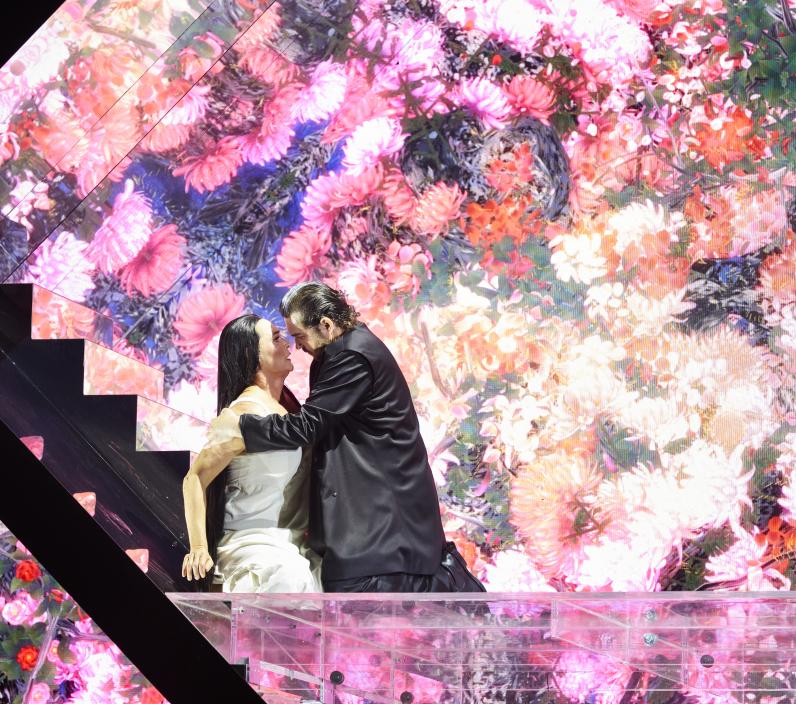

Ping, Pang and Pong share a picnic off-duty. They drink heavily and lament their servitude to Turandot’s bloodlust; they lament the lives they might have once had in some other sweet imagined home. Will they ever be free? The trumpets sound: duty calls them back to produce Calaf as the next Suitor in Turandot’s Riddle Games. The crowd arrive, hungry for another spectacle of gladiators and blood. The powers that be process and present the Emperor. He, too, wishes his daughter’s trail of blood would end. The golden bride-prize, Turandot, arrives. She tells the Suitor of her numb heart’s will to stop the lineage of trauma inflicted by men on her female ancestors — mental, physical abuse, rape and murder. No man will claim Turandot like that. Miraculously, Calaf solves the first riddle, the second … the third. The crowd goes wild, the Bride and Groom are quickly prepared for the wedding. Trembling in her wedding dress, Turandot pleads with her father to not force this marriage. Seeing and hearing her pain once more, Calaf extends a shocking, gentle gesture to his prize, Turandot; a riddle of his own. “If before morning you can discover the name I bear, I shall forfeit my life.”

ACT 3

The entire city hunts all night to find Calaf’s name. Calaf remains alone inside the ritual space, determined that dawn will deliver Turandot to his arms. Ping, Pang and Pong offer Calaf any price in return for his name: women, jewels, safe escape; but Calaf will have none. He returns to the altar to receive Turandot’s answer to his riddle, but instead sees Timur and Liù taken prisoner. Turandot believes torture will reveal the truth she seeks. Instead, Liù chooses to take her own life. Timur follows suit. Turandot is shaken by the depth of Liù’s love for Calaf, and her own cruelty which led to an innocent women’s death — like the very men she detested. Calaf reproaches Turandot who still tries to avoid her fate of marriage. Calaf leads her on a final unexpected journey. In an act of sublime gentility and understanding, Calaf offers Turandot the metaphoric sacrifice she needed to see from one man to open her heart. Turandot and Calaf embrace. The Emperor is finally free to pass — the new Emperor and Empress appear before their people.

INSIGHTS

Four Questions to Director Daniel Kramer

Turandot is a fabulous mythical masterpiece. What is your take on this enigmatic tale?

Calaf is our gateway to the plot; the opera might have been called Calaf, although the object of his desire is Turandot. For me, the first question is: what journey does Calaf undertake through his encounter with Turandot? Why inwardly does he need this journey, and where in the modern world do we see others needing this journey as well?

We first meet young Calaf lost in the crowd who have come to see another man trying to win - and lose - Turandot as a wife. The punishment for having lost in this world is simpy ‘Off with his head!’ But on seeing Turandot for the first time, Calaf becomes obsessed - as one becomes obsessed with a goddess. He ‘loses his head’ when he sees her. Her music is intoxicating, wild, illogical, incendiary. He shall have her or pay with his life. Calaf, like Wagner's Tristan, projects his need for a feminine divinity onto Turandot. And with little heed to whoever tries to dissuade him, he is determined to drink from this sacred cup, even if it means paying the ultimate price.

Turandot performs a dark ritual by beheading men who cannot solve her riddle. What is the connection between Puccini and this theme?

In 1924, when Puccini was composing this opera, Italian society around him after World War I saw women taking up many new professions. These changes scared off many men, not least Puccini himself, if some of his letters are to be believed. Consciously or otherwise, I believe that Puccini explored his own magnetic attraction: the fear of the powerful, all-creative, all-consuming women in his life, young women in particular.

Music so often touches on the divine, perhaps better than any other art form. In his score, as in his life, there is such a clear adoration, passion and romanticism towards women. But women are not always cast in a positive light. More than in any other of his operas, the main female role expresses pain, an overwhelming emotion that drowns out everything in his presence. We cannot ignore the fact that he wrote a scene where an innocent woman, Liù, is tortured for fourteen minutes on stage.

I will leave the psychoanalysts to unpack the complexity of this in Puccini's personal psyche. But the whole opera seems to be a musical purge of his complex feelings about women: their closeness to the Virgin Mary, their emotions that threaten to drown out men, their power to enchant, their vulnerability, and even feelings of hatred, which are matched only by his sexual desire for them.

The Beijing crowd is an ambivalent mob. How do you see the role of chorus in this opera?

The society we portray is key to accentuating Turandot's story of female power over man, as well as Calaf's fear of being worthless in the eyes of women and power. The opera is directly inspired by the Roman Colosseum, with its gladiators and spectators. In modern stadia, the crowd wants sport, fights, drama, blood, sex and death - winners and losers. The crowd reflects our modern impulses as users of social media; entertainment and distraction from our (overworked, underpaid, complicated) lives, corrupt men and governments. When Turandot puzzles suitors, beheads losers, and marries the winner, it's almost like a monthly game show for the masses.

It is the same system that we use today to anaesthetise and suppress the mass, to keep the people following what the leaders have decided, to keep the machines churning that channel big bucks to the 1% of those who profit from the blood, sweat and stupidity of ordinary families, giving them the illusion that their lives matter.

In Geneva, we have chosen to end the opera with the finale by Berio of Puccini's unfinished work. What have you discovered in the relationship between Puccini and Berio?

Choosing Berio was a direct response against the bombastic version of Alfano (1926), which smacks more of Disney sentimentality than Calaf's taking charge as an equal to Turandot's power. Wisely, instead of trying ‘to be Puccini’ or ‘please commercially’, Berio gives us a lot more space, literally more instrumental music. If Alfano tends to get things wrong and overdo it for the masses of the Coliseum, used to being fed substandard sentimental fodder and happy endings, Berio tried to dig deeper into the inner truth of a woman; one who is hurt, abused and finally lets herself be touched by a gentle and kind man. Berio's darker and dangerous textures embody two souls that seem to have changed on a spiritual and philosophical level. His music takes us to a new space, and especially to a new time: the reign of Turandot is coming to an end.

We have been waiting for the Age of Aquarius for thousands of years now. And here we are in 2022, where we witness the desperately desolate male patriarch which governs with almost more fear, greed and violence than ever before. Think Trump, Putin, Bolsonaro, Xi. No wonder depression is a global pandemic. Will this male inferiority complex ever be truly liberated? Calaf gives us hope.

Adapted from an original interview between Daniel Kramer and Stephan Müller

GALLERY