Not your typical fairytale princess

The story of Turandot originated in a French fairy tale collection by François Pétis de la Croix called Les mille et un jours (‘The thousand and one days’, not to be confused with the more famous One thousand and one nights). As many of these stories have only been found in de la Croix’s version, numerous scholars wondered whether he had made them up himself. In the case of Turandot, however, the origin seems to lie in a 12th-century story by the Azerbaijani poet and philosopher Nizami Ganjavi, ‘Seven Beauties’.

Puccini discovered the tale through Schiller’s play, which derived from the German version of an Italian commedia dell'arte by Carlo Gozzi, who in turn took the story from the de la Croix. What a detour! Puccini was not the first composer to take an interest in this colourful tale. Antonio Bazzini wrote Turanda in 1867, Ferruccio Busoni Turandot in 1917 only a few years before Puccini began his version.

‘Here the maestro put down his pen’

If Puccini was always known as meticulous, the writing of Turandot was particularly strenuous. In the four years before his death, Puccini was indecisive over the number of acts and specifically obsessed over the final love duet. In his eyes, it should become the all-important culmination of the opera. ‘I have placed, in this opera, all my soul,’ he wrote to a friend in March 1924. He died in November of that year.

After Puccini’s death, his friend Arturo Toscanini, who would conduct the premiere, suggested that the young composer Franco Alfano should finish the score. Although Alfano had Puccini’s sketches at his disposal, much of them were hard to interpret. Of the love duet, for instance, Puccini wrote puzzlingly ‘Then Tristan…’, in reference to Wagner’s opera which ends with Isolde exalted Liebestod (love death).

Turandot premiered at La Scala in Milan in April 1926. Famously, when the opera reached the last note written by Puccini, Toscanini ended the performance, saying something to the lines of ‘Here the Maestro put down his pen’. The Alfano version was only presented the following night.

A darkly enchanted world

Ricci/Forte’s production also follows Alfano’s ending. ‘After the first reading, we thought that the opera should end with Liu's death. But later we realized that the emotional trajectory seeks a happy ending. After all, we have enough disappointments and sad ends in real life‘, explains Stefano Ricci, who forms the duo Ricci/Forte with Gianni Forte, known for their experimental, sometimes provocative staging which could be seen on OperaVision with Nabucco. For them, the opera takes place in an enchanted world: ‘everything happens in Turandot's head, like a vision that allows her to make the characters act as she pleases’.

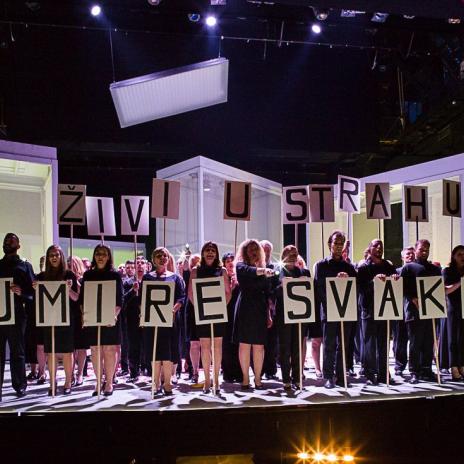

Twelve dancers representing her toys - shadows of past failed relationships - are on stage all the time with Turandot. Rebeka Lokar, who sings the title role, says of her character ‘Turandot is a young, intelligent girl. She’s not a typical fairytale princess, but she’s not a witch either. She is a young girl full of fears, because of which she pushes people away from her.’

‘Our main goal was to convey the fiction of a fairy tale,’ Forte points out. ‘Turandot is actually the director of this opera. She is a person who pulls the strings on her dolls, introduces us all to her world, which is actually the world of her imagination, but the only one in which she feels safe,’ explains Ricci. No chinoiserie, no orientalism can be found in this production.

‘Puccini loved the East very much and on one occasion he was at an Eastern dinner. There was a music box playing three tunes. Puccini takes the number three as a magic number from fairy tales. Turandot has three assistants, Ping, Pang and Pong, there are three puzzles that Calaf needs to solve, there are three acts.’, adds the conductor Marcello Motadelli. ‘For Puccini, the theatre was like that magical music box, like a fairy tale where anything is possible.’