The Other Weill

To many, Kurt Weill goes hand in hand with Bertold Brecht. Their collaborations, in particular The Threepenny Opera and Rise and Fall of the City of Mahagonny, are biting social satires critiquing capitalism, corruption and economic crises. Indeed the encounter between the young Jewish composer Weill and the socialist playwright Brecht brought about a revolutionary new genre of musical theatre that did not shy away from radical politics and controversy. The premieres, starring Weill’s wife Lotte Lenya, established Weill as a fixture of 1920s Berlin’s vibrant cultural scene and one of the most successful composers of the Weimar Republic.

With the rise of national socialism, their productions were increasingly attacked. Even though Weill’s operas continued to enjoy popular success, Nazi protests routinely interrupted their performances and theatre directors became more loath to stage his work. Just like many other artists in his predicament, Weill repeatedly misjudged the political developments and believed that things would get better already. When he finally discovered that he and his wife were officially blacklisted by the Nazis and were to be arrested, he travelled to France in March 1933, in the hope that his stay in Paris would only be temporary. There, he collaborated with Brecht for one last time on the ballet The Seven Deadly Sins.

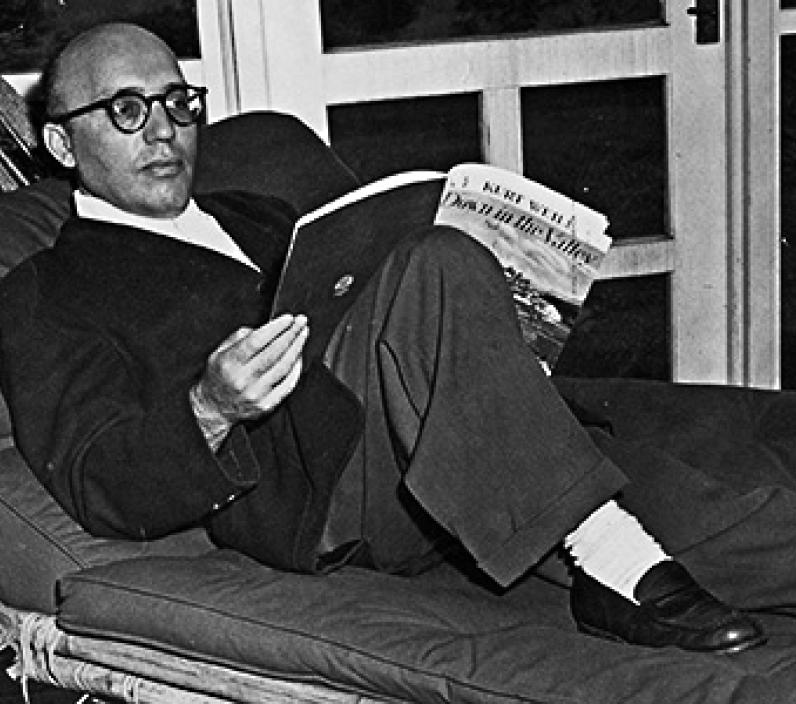

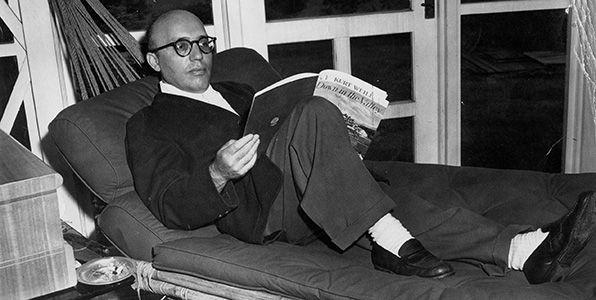

Weill’s oeuvre did not end with his exile from Germany, nor did his career draw to a close with the end of his collaboration with Brecht. In September 1935, Weill moved to New York with his wife, became a naturalised citizen in 1943 and allegedly refused, despite his broken English, to converse with his wife in German, the language of the perpetrators’.

Where does he go from here?

This emotional break was accompanied by a stylistic one. The first couple of years in the US were a struggle for him, his plays did not meet expectations and the couple had trouble supporting themselves. It was only in 1938 that Weill gained access to the Broadway theatre scene with his musical Knickerbocker Holiday written with playwright Maxwell Anderson. He worked with Ira Gershwin on the film Where do we go from here? and the musical Lady in the Dark, a rare popular exploration of psychoanalysis at the time. Unique among Broadway composers of the time, Weill insisted on composing his orchestrations himself.

‘As far as I am concerned, I compose for today. Posterity doesn't interest me one bit.’

Many critics have pitted Weill’s early work against his later material written in Paris and the US and accused the later phase as being superficial. Yet Weill’s novel musical approach combined both commercial success and artistic aspiration, as in his 1946 opera Street Scene, based on a play by Elmer Rice with lyrics by Langston Hughes. Weill was awarded the inaugural Tony Award for Best Original Score for this work. His output in exile has stood the test of time and shaped the development of the American musical. So even though he might not have been interested in posterity, posterity is certainly interested in him.