Queens in Opera

Sing, Suffer and Slay – Queens Take the Stage

Coloratura-flinging divas, dignified regents, noble sufferers, emancipated warriors against patriarchal structures – queens in opera are not always easy to grasp and yet they are each equally fascinating. While real-life royalty has played an important role in opera as commissioners and dedicatees, composers have also repeatedly used royal characters in their works to reflect power structures and express social criticism. As a result, opera is full of historical and fictional queens who divide, entertain or inspire audiences in different ways.

Extravagant

By far one of the most famous opera queens of the 18th century is the Queen of the Night from Mozart’s The Magic Flute (1791). As nameless ruler over the dark side of the world, a world of the obscure and the mysterious, she throws her claim to power in the shape of sharp coloraturas into Mozart’s fairy-tale world. At the end of the opera rendered harmless by the “power of the sun” (i.e. the Enlightenment), she has to surrender to her dramaturgical fate as a woman subordinate to a man, but at least musically, she remains in the ears of the audience for a long time.

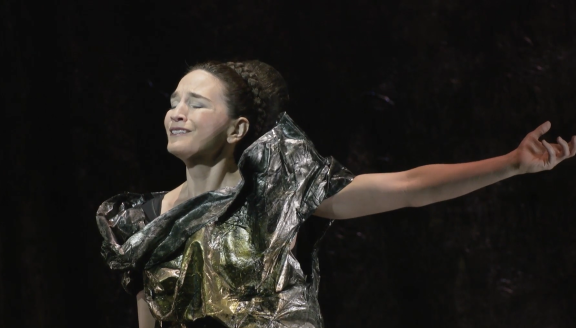

Such mystical queens are usually rather one-sided and reduced to a clear stereotype; they captivate with their extravagance and provide real “wow” moments with their vocal excellence. They are most often found in operas with fairy-tale themes (such as the Queen of Hearts in Alice in Wonderland or the Snow Queen), where they embody bygone times and timeless ideas.

Tragic

According to the drama theory principle of the “Fallhöhe” (height of fall), the higher the heroine’s social and moral status was before, the more poignant is her fall. The same applies to opera: the higher the status, the more beautiful the suffering. Before opera genres such as verism also allowed everyday folk to suffer in musically extravagant ways, it was mainly aristocratic and royal characters who had a lot to lose in a tragedy and, thus, were allowed to suffer on a grand scale.

A prime example of this type is Dido, Queen of Carthage, for whom Henry Purcell composed a deeply moving swan song in Dido and Aeneas (1689). Dido is no glamorous ruler, but suffers from an undying longing for her dead lover, to whom she has sworn eternal fidelity. When the attractive stranger Aeneas arrives, Dido gains new hope; but struck by his sudden departure, Dido sees no way out but death. Her final aria, When I am laid in Earth, is one of the most beautiful ever written for the operatic stage: from the descending bass figure to Dido’s breathless repetition of her heartfelt wish (“Remember me!”) to her resolute farewell (“But ah! forget my fate”).

There is a touching radicalism in the extreme transformation that Dido undergoes in this short opera and in the range of her fall from her position of power to the abandonment of her own existence. Not only because, in the end, we can identify emotionally with a socially superior queen. In her vulnerability, Dido becomes a universal principle; her farewell ‘not just the lamentation of one person over the world, but the lamentation of the whole world in one person’ (Ulrich Schreiber).

Torn Apart

Gaetano Donizetti placed historical queens at the centre of three operas: Anna Bolena (1830), Maria Stuarda (1834) and Roberto Devereux (1837), all of them an Italian’s perspective on the English monarchy. The roles of Anne Boleyn, Mary Stuart and Elizabeth I (who appears in two of the operas) are among the most technically demanding in the bel canto repertoire. They also epitomise the type of queen whose dual role as state and private person makes her a psychologically exciting character, torn between her social duties and personal desires.

In Maria Stuarda, two queens vie for power: the English ‘Virgin Queen’ Elizabeth I and the Scottish Mary Stuart, who challenges the other for the throne. Both are queens and women who doubt, fight and give everything to maintain their political position. Donizetti sets up their confrontation before Mary’s imminent execution as a real showdown. The full extent of the royal scandals is expressed here in a fierce battle of words. On the occasion of her debut in the title role, soprano Diana Damrau described this intense scene: ‘This confrontation is madness: there are two tigresses, two battleships... And then it escalates! In the history of opera there is hardly another encounter like this between two sopranos.’

“Figlia impura di Bolena”, “meretrice indegna e oscena”, “vil bastarda” (Boleyn’s impure daughter; low and lustful harlot; vile bastard) – Maria’s notorious curses are not expressions of state; rather, they are based on a deep personal hatred, which eventually seals her fate. Do opera audiences care whether these depictions are historically authentic? Well at least, we can say that they take pleasure in the glimpse into the private lives of the royals – albeit through the artistic lens of an opera composer.

Murderous

Then there is the type of queen who will literally walk over dead bodies to prevail against their adversaries and to defend her own interests. These queens are fascinating, less for their diplomatic skills than for their radical, transgressive behaviour, which sends shivers down the spine of all fans of thriller and true crime.

A prominent representative of this category is Shakespeare’s risen-to-queen Lady Macbeth. In Macbeth (1847), Giuseppe Verdi made her one of the ultimate villains in the operatic repertoire. To ascend to the throne, Lady Macbeth incites her husband to murder; she then does everything in her power to get rid of the men who stand in her way. In her obsession with power, decisiveness and ruthlessness, she is far from the Elizabethan ideal of womanhood, which in turn makes this bloody lady a popular model for modern works such as Shostakovich’s Lady Macbeth of Mtsensk.

But not every murderous queen is ‘all evil’. It is more exciting to understand their motives and actions, and to see how far we can sympathise with them. Take the example of Penthesilea: the Amazon queen from Greek mythology is betrayed in her love by Achilles, whereupon she kills the warrior, or more precisely, tears him to pieces. In 1808, the German playwright Heinrich von Kleist created an uproar with his tragedy of the enraged queen, which inspired Othmar Schoeck to write his opera Penthesilea (1927); in the lead role, a dramatic mezzo-soprano, of course. The piece culminates in a tense monologue by Penthesilea in which she realises her fatal mistake, expressed in a tragically and beautifully manner: “Did I kiss him dead? […] So it was an accident. Kisses, bites, / That rhymes. and he who loves with all his heart / Can easily take one for the other.”

Hannes Föst

Translated from the German original