A philandering nobleman lives without a care for the consequences of his actions. But when one of his conquests ends in murder, he finds himself on the run, pursued by disgruntled ex-lovers, fiancées and a force from beyond the grave.

Following his recent spectacular production of Paria, the renowned British director Graham Vick makes a welcome return to OperaVision with this new Don Giovanni from Rome. Italian baritone Alessio Arduini plays the dishonourable Don alongside Georgian soprano and Moniuszko International Vocal Competition winner Salome Jicia as Donna Elvira. This performance is part of OperaVision’s events celebrating the inaugural World Opera Day on 25 October 2019.

Cast

|

Don Giovanni

|

Alessio Arduini

|

|---|---|

|

Leporello

|

Vito Priante

|

|

Masetto

|

Emanuele Cordaro

|

|

Il Commendatore

|

Antonio Di Matteo

|

|

Don Ottavio

|

Juan Francisco Gatell

|

|

Donna Anna

|

Maria Grazia Schiavo

|

|

Donna Elvira

|

Salome Jicia

|

|

Zerlina

|

Marianne Croux

|

| ... | |

|

Music

|

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart

|

|---|---|

|

Conductor

|

Jérémie Rhorer

|

|

Director

|

Graham Vick

|

|

Sets

|

Samal Blak

|

|

Lighting

|

Giuseppe di Iorio

|

|

Costumes

|

Anna Bonomelli

|

|

Text

|

Lorenzo Da Ponte

|

|

Chorus master

|

Roberto Gabbiani

|

| ... | |

Video

The story

Act I

Don Giovanni, a Spanish nobleman, is renowned throughout Europe as a seducer of women; Leporello, his servant, reluctantly aids him by keeping watch. Giovanni attempts to leave the house of Donna Anna, his most recent conquest; he kills Anna’s father the Commendatore when the Commendatore tries to stop him. Anna tells her fiancé, Don Ottavio, that she was raped by an unknown man and they vow revenge on the murderer.

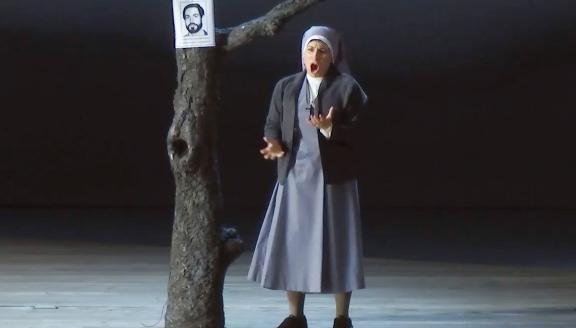

Leporello’s attempts to persuade his master to reform are interrupted by Donna Elvira, a former mistress of Giovanni’s, who is travelling to look for him. Giovanni leaves it to Leporello to explain the extent of his master’s womanizing.

Masetto and his bride Zerlina are to be married at a peasant wedding, but Giovanni sets himself to seduce Zerlina. Elvira interrupts and foils Giovanni’s attempt. Ottavio and Anna appeal to Giovanni for help in their pursuit of the murderer of Anna’s father. Elvira again interrupts and warns Ottavio and Anna about Giovanni’s true nature; Anna tells Ottavio that Giovanni is the man who murdered her father.

Leporello discusses with Giovanni the plans for the masque ball his master is hosting that evening. Zerlina assures Masetto that Giovanni has not touched her. Elvira joins forces with Ottavio and Anna; they are going to the ball and intend to exact vengeance on Giovanni. While everyone is dancing at the ball Giovanni attempts to ensnare Zerlina, but she rallies all behind her to try to entrap Giovanni. All accuse him, but he and Leporello elude them once more.

Act II

Hoping for success with Elvira’s maid, Giovanni exchanges clothes with Leporello, who is instructed to lure Elvira away. Giovanni is interrupted by Masetto, who is intent on killing him, but his disguise is successful and he beats Masetto up and escapes.

Returning with Elvira, Leporello is mistaken for Giovanni by Anna, Ottavio, Zerlina and Masetto. Removing his disguise, Leporello convinces them that he is not the guilty one. Ottavio swears vengeance on Giovanni whom, in spite of everything, Elvira continues to love.

Giovanni hears the voice of the Commendatore, whom he killed, warning Giovanni of impending retribution. Giovanni orders Leporello to invite the ghost to supper. The ghost of the Commendatore accepts Don Giovanni’s invitation and arrives to send him to hell.

Insights

5 things to know about Don Giovanni

1° A Spanish play

The character we know as Don Juan first emerged around 1630 in Counter-Reformation Spain as the protagonist of the play El Burlador de Sevilla y convidado de piedra (The Trickster of Seville and the Stone Guest), which was written by the Spanish friar Tirso de Molina.

The Burlador, named Don Juan Tenorio, has three good qualities in the eyes of his peers: noble birth, great courage and adamant fidelity to his word. Otherwise, he is good for nothing: a shameless bully, a seducer, and a grandee too quick with his sword who recklessly skewers the father of one of his conquests. At the end of the play, the father’s ghost has his revenge when he invites Don Juan for dinner at his tomb, where he strikes him dead.

2° A ridiculed legend

By the time Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart and Lorenzo Da Ponte started working on Don Giovanni in 1787, the legend of the godless libertine and enemy of society had become intellectually discredited. Whereas, a century before, Molière could treat it as a suitable subject for high drama, by the late 18th century it had sunk to the level of pantomime, fit only for the fairground or, if handled by serious playwrights, rationalised, with the supernatural suppressed.

Don Giovanni Tenorio, the contemporary one-act opera by the Italian composer Giuseppe Gazzaniga with a libretto by Giovanni Bertati that da Ponte borrowed heavily from, opens with a prologue in which the actors are shown reluctantly agreeing to put on ‘this piece of rubbish’ because the common people always flock to it and the company needs a hit.

3° Dramma giocoso

Mozart, however, had other ideas. Yes, his opera would be filled with jokes, but there is no chord in the whole of music that is darker or more thrillingly ominous than the D-minor chord that launches the overture. It signals straightaway his intentions to take the subject matter, including the supernatural element, seriously.

This precarious mixture of playfulness and darkness is reflected not only in Mozart's music and also in the sub-genre of the opera itself. The Italian term dramma giocoso - literally, ‘playful drama’ - which Mozart applied to Don Giovanni is at once a contradiction in terms as well as the very essence of music itself. Throughout the opera, the more the subjective situation of a character becomes tragic, the more comic is the objective situation, and vice versa. For instance, the catalogue aria of Leporello in Act I in which he recounts the endless (and probably unsuccessful) exploits of his master is extremely humorous for Leporello, but shockingly tragic for Elvira, who thus discovers Giovanni’s unfaithfulness.

4° Real-life Don Juans

Da Ponte may have been a fine poet with a passion for the classics of Italian and Latin literature, but he was also a shady character – an unfrocked priest, a boaster and a womaniser. Perhaps the most real-life Don Juan character in European history, however, is Giacomo Casanova. The legendary Venetian libertine met Da Ponte in Prague at the time of the opera's first production and may have met Mozart at the same time. There is reason to believe that he was also in Prague in 1791 for the coronation of Holy Roman Emperor Leopold II as king of Bohemia, an event that included the first production of Mozart's opera La clemenza di Tito.

Casanova is known to have drafted dialogue suitable for a Don Juan drama at the time of his visit to Prague in 1787, but none of his verses were ever incorporated into Mozart's opera. His reaction to seeing licentious behaviour like his own held up to moral scrutiny as it is in Mozart's opera is, sadly, not recorded.

5° Danger and play

‘Everybody loves a bad boy,’ says Graham Vick, the director of this new production at the Teatro dell’Opera di Roma. ‘The bad boy always has great appeal, for both men and women. For us men, because we all want to be him, we desire the courage to live like him.’

Giovanni radiates an attitude that all women need him far more than he needs them, and that he is invulnerable to their charms. Although associated with sensuality and sophistication, he represents the men that prey on women for the sake of conquest alone. For him, as with the Pick Up Artists of today, it's the thrill of the hunt itself that is the goal. ‘The true man wants two things: danger and play,’ wrote Friedrich Nietzsche in Thus Spoke Zarathustra. ‘Therefore he wants woman, as the most dangerous plaything of all.’

Gallery