As Aragon descends into unrest, a count jealously fights for a noble lady's heart. But she has already given it to a passionate troubadour whose mother holds a terrible secret.

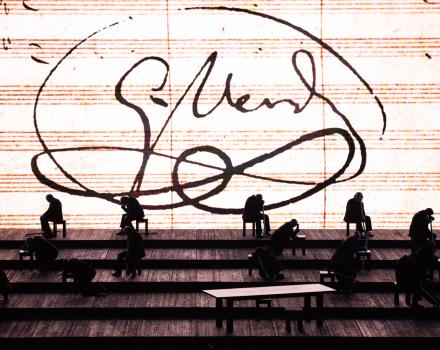

Surpassing its hugely successful spiritual predecessor Rigoletto, Il Trovatore was an instant triumph. Verdi’s music is so passionate and transcendent that one almost loses sight of opera’s notoriously most implausible plot, complete with burning babies and bloodthirsty vengeance. British baritone Christopher Maltman stars as Count Di Luna against the breathtaking backdrop of the ancient Roman Circus Maximus.

Cast

|

Count di Luna

|

Christopher Maltman

|

|---|---|

|

Leonora

|

Roberta Mantegna

|

|

Azucena

|

Clémentine Margaine

|

|

Manrico

|

Fabio Sartori

|

|

Ferrando

|

Marco Spotti

|

|

Ines

|

Marianna Mappa

|

|

Ruiz

|

Domingo Pellicola

|

|

Old gypsy

|

Antonio Taschini

|

|

A messenger

|

Aurelio Cicero

|

|

Chorus

|

Teatro dell’Opera di Roma Chorus

|

|

Orchestra

|

Teatro dell’Opera di Roma Orchestra

|

| ... | |

|

Music

|

Giuseppe Verdi

|

|---|---|

|

Conductor

|

Daniele Gatti

|

|

Director

|

Lorenzo Mariani

|

|

Sets

|

William Orlandi

|

|

Lighting

|

Vinicio Cheli

|

|

Costumes

|

William Orlandi

|

|

Text

|

Salvadore Cammarano

|

|

Chorus master

|

Roberto Gabbiani

|

| ... | |

Videos

The story

Act I

THE DUEL

The guard room in the Aljaferia Palace in Zaragoza, the residence of the kings of Aragon. In a hall of the palace, the men-at-arms of the Count of Luna are keeping watch. Ferrando, the captain of the guards, tells the story of the present Count’s younger brother, Garzia: one day many years ago, a gypsy woman, caught lurking near the baby’s cradle and suspected of witchcraft was condemned to be burnt at the stake. The witch’s daughter, Azucena, avenged her mother by kidnapping the child. Sometime later, in the same spot where the witch had been burnt to death, were found the blackened bones of an infant. No one ever doubted that they were of the hapless child.

The gardens of the palace. Leonora, a lady-in-waiting to the Queen, is telling Ines how she fell in love with an unknown knight, the admired victor of a tournament. The outbreak of civil war has prevented her from seeing him again. While the two women withdraw to their apartments, the Count of Luna comes upon the scene. He is in love with Leonora and has finally made up his mind to declare his love. But a voice raised in song halts him and inflames his jealousy; it is Manrico, the unknown knight. Hearing his voice, Leonora comes down into the garden. In the darkness, she mistakes the Count for the troubadour and tremulously goes towards him. When she realizes her mistake, she tries to explain it to the disappointed Manrico. Meanwhile, the Count has recognised in his rival a follower of the outlawed Count of Urgel. This is yet another reason for challenging Manrico to a duel. Leonora faints while the men, drawing their swords, prepare to do battle.

Act II

THE GYPSY WOMAN

The camp of the gypsies in the mountains of Biscay. Manrico has been wounded and has taken refuge with Azucena, the gypsy of Ferrando’s story, whom he believes to be his mother. The gypsy relates the tragic outcome of her attempt to avenge her mother’s dreadful, unjust death. Crazed by grief, a fatal error caused her to throw into the burning pyre not one of the old Count of Luna’s two sons, but her own child. Manrico, amazed at this revelation, asks her who he is, then. But Azucena quickly regains command of herself and takes back her confession, reminding him of the many proofs of her love that she has given him. Not the least of which is the healing of the wounds he suffered in the battle of Pelilla at the hands of the young Count of Luna, who thus repaid him for sparing his life the night of the duel. Manrico confesses to Azucena, in fact, that at the very instant in which he was about to despatch his opponent, a secret impulse, stronger than his conscious will, halted his hand. A messenger brings Manrico orders to take command of the newly conquered citadel of Castellor; he also informs him that on hearing the false news of his death, Leonora has decided to take the veil. Deaf to Azucena’s entreaties, Manrico rushes off.

A convent near the citadel of Castellor. With his followers, the Count enters by stealth the convent to abduct Leonora, but his plans are foiled by the arrival of Manrico. Surrounded and disarmed by Manrico’s men, he flees to avoid falling a prisoner to them. Leonora, overjoyed at having found Manrico alive, goes off with him.

Act III

THE SON OF THE GYPSY WOMAN

Luna’s camp under the walls of Castellor. The Count’s soldiers are encamped under the walls of Castellor and, incited by Ferrando, they prepare to do battle once again. The Count is tortured by the thought of Leonora in Manrico’s arms and by his anxiety to get her back. Meanwhile, some of his soldiers come upon a gypsy woman, Azucena. They question her and from her words, Ferrando recognises in her the daughter of the witch who stole the Count of Luna’s younger brother. Azucena denies their accusations and justifies her presence in the neighbourhood by saying that she has come to seek her son, Manrico. On hearing this hated name, the Count decides, solely for the joy of causing Manrico terrible grief, to condemn Azucena to death.

A chamber near the chapel in the citadel of Castellor. Although their happiness is clouded by the knowledge of the imminent enemy attack, Manrico and Leonora are about to celebrate their marriage in the chapel of Castellor. But the ceremony is interrupted when Manrico, learning from Ruiz that Azucena is to be burnt at the stake, rushes off to attempt to rescue her.

Act IV

THE PUNISHMENT

Before the dungeon-keep in the Aljaferia Palace. Manrico has been taken prisoner, and Ruiz guides Leonora to the tower where he has been imprisoned. Leonora pours out her grief and is answered by Manrico’s song, while an invisible choir chants the solemn notes of the ‘Miserere’. From the palace of Aljaferia Count of Luna arrives and confirms the order that at dawn Manrico is to be beheaded and Azucena burnt alive. Leonora comes out from her hiding place and swears to be his if he will grant Manrico freedom. The Count eagerly accepts her offer, but Leonora stealthily takes the poison concealed in a ring she is wearing.

In the dungeon. Manrico and Azucena are waiting, with very different sentiments, to meet their death: Azucena with terror at the thought of the stake, Manrico with fortitude and resignation. Leonora enters their cell and announces that she has obtained Manrico’s freedom. He, however, guessing at the infamous bargain that has been the price of his release, scornfully rejects her until Leonora reveals that to avoid giving herself to the Count, she has taken poison. The Count enters and surprises them in the moment of their last tragic farewell. Furious at the trick Leonora has played on him, he orders Manrico to be executed immediately. Azucena shakes herself from the stupor into which she had fallen and reveals to the Count the story of the exchange of the two children so long ago. Manrico was Garzia, her mother is avenged. The Count’s horror at having had his own brother put to death is all in vain.

Insights

An immaterial, dreamlike and mysterious atmosphere. Interview with director Lorenzo Mariani

How do you build this atmosphere in an opera production for an open-air stage?

Open-air opera with amplification is always a tiring and problematic job for a director. I chose to follow a metaphysical line, with an immaterial, dreamlike, mysterious atmosphere. I rely precisely on geometric, anti-naturalistic elements, starting of course with the proportions of the triangle, perfect for a work in which Verdi knows how to transform archetypes into a living passion. There are no allegories in the opera, but it is certainly possible to identify certain symbolic elements, and it is not by chance that Luciano Berio started from the elementary conflicts of Il trovatore to begin his work La vera storia. For this reason, too, I have dedicated myself to the immanent presence of the sky.

Putting the sky on the screen in competition with that which stretches over the Palatine!

Even more prominently, because when the show begins the sky above us gradually disappears into the night. In any case, for me, it is essential to remain in an immaterial context, a dream world that we could compare to the visual distillation of the skies in Bergman's The Seventh Seal or those in Ejzenštejn's Aleksandr Nevsky. The use of the sky allows me to change the atmosphere with remarkable rapidity, exactly as the dramaturgy of the work requires, so the sky can suddenly be crossed by lightning or by flames. At the same time, I worked on the geometry of the spaces to arrange and make the chorus act while respecting the health protocols that continue to influence the movement options. There are no castles or camps: Luna and Leonora's world is dark, with black tables and stools. By contrast, Azucena and Manrico’s world is all white. Each character, from Ferrando to Leonora, from the Count of Luna to Azucena, tries to shed light on the story with a candelabra as if inhabiting a great Gothic tale.

Was it difficult to manage the large size of the stage?

Less than I would have expected, also considering that I don't use screens to frame characters. In Il trovatore this need is less important, just like the proximity between characters, who are often divided and in conflict with each other: in this way we can also more naturally respect the singers' need to look at the audience and the conductor in some demanding passages without affecting the overall outcome of the scenes.

The central figure of the opera, who dominates the story from the bloody antecedent to the final revelation, remains Azucena, the true driving force of the story.

I found the musicologist Lorenzo Bianconi’s analysis useful, in which he distinguishes the figures inhabited by the feeling of love from those essentially driven by a desire for revenge. The latter in turn also have feelings of love, the Conte di Luna is even obsessed with love for Leonora. Just as Azucena in turn desperately and perhaps morbidly loves her strange son Manrico, to the point that she manages to find him alive on the battlefield of Pelilla, groping for him among thousands and thousands of fallen soldiers, which is as unrealistic as it is eminently symbolic. In outlining Azucena, I think it is sufficient to make clear the constant presence of a traumatic experience; in contemporary terms, we would speak of a syndrome, post-traumatic stress disorder. Verdi shows us this clearly: not a day passes that Azucena does not relive the capture and burning of her mother. Moreover, the character had fascinated Verdi so much that he planned to call the opera La Gitana, which in this edition is performed by Clémentine Margaine, with a remarkable voice and temperament.

Then there are the Conte di Luna and Manrico.

I like the character of the Count very much, an obsessive who does not sleep for days just to see the face of the one he loves against everything and everyone, to the point that he is not afraid to sacrifice God in order to take Leonora away from the altar. Once again, even if outside a realistic development path, the character is incredibly exciting, especially when set with an actor of Christopher Maltman's quality. With Fabio Sartori, who showed an extraordinary involvement in the character of Manrico, we worked on Manrico's amorous and naïve side. Manrico is not only a muscular hero but also a lost young man, just think of his astonished reaction to the sudden revelation of his real identity, immediately concealed by Azucena. I was struck by the marked growth of soprano Roberta Mantegna, with whom I had already met, who dominates her expressive part with ever greater fluency and freedom.

In Il trovatore, we have a gypsy woman, frowned upon and suspected precisely because of her ethnicity, marked as a witch. How do these issues affect your profession today?

Opera is based on universal themes, common to all mankind: my impression is that when you try to instrumentalise certain social themes, you risk irreparably restricting the artist's message. The beauty and power of music are essentially based on non-conceptual processes, which is why I am not at all convinced by life jackets and migrants brought to the stage by bending the meaning of an opera libretto - it is another thing when they are called upon by the libretto or a play text to provide some additional explanation or meaningful solution to the problems that plague our world. At the very least, one has to be very careful. I have always been struck by a letter from Tolstoy that I would like to quote at the end of our meeting: ‘The purpose of art is not to solve problems, but to force people to love life.’

The questions were asked by Andrea Penna

Gallery