In the trenches, soldiers are locked in endless fighting: they move some kilometres forward only to return back to their former position in a deadly cycle. Elsewhere, a woman returns to a house she has once known and finds it now poised at the edge of an abyss. Wanting to leave, she encounters inexplicable obstacles.

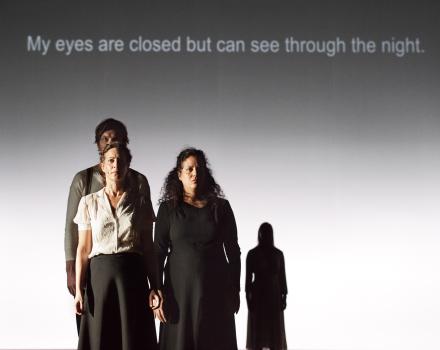

Chaya Czernowin’s harrowingly sublime work Infinite Now interweaves two seemingly unconnected storylines - Luk Perceval’s play FRONT based on Erich Maria Remarque’s novel All quiet on the Western front and Can Xue’s novella Homecoming - that both speak to the human condition of entrapment and existential nakedness, and beyond that to a will to survive.

Cast

|

Sopranos

|

Karen Vourc’h

|

|---|---|

|

Mezzo-soprano

|

Kai Rüütel

|

|

Alto

|

Noa Frenkel

|

|

Contratenor

|

Terry Wey

|

|

Baritones

|

Vincenzo Neri

|

|

Bass

|

David Salsbery Fry

|

|

Paul Bäumer

|

Rainer Süβmilch

|

|

Katczinsky

|

Benjamin-Lew Klon

|

|

Lieutenant De Wit / Van Outryve

|

Didier De Neck

|

|

Colonel Magots

|

Gilles Welinski

|

|

Soldier Seghers

|

Roy Aernouts

|

|

Sister Elisabeth

|

Oana Solomon

|

|

Guitar

|

Nico Couck

|

|

Electric Guitar

|

Yaron Deutsch

|

|

Cello

|

Christina Meissner, Séverine Ballon

|

|

Orchestra

|

Symfonisch Orkest Opera Ballet Vlaanderen

|

| ... | |

|

Music

|

Chaya Czernowin

|

|---|---|

|

Conductor

|

Titus Engel

|

|

Director

|

Luk Perceval

|

|

Sets

|

Philip Bussmann

|

|

Lighting

|

Mark Van Denesse

|

|

Costumes

|

Ilse Vandenbussche

|

|

IRCAM Computer Music Design

|

Carlo Laurenzi

|

|

IRCAM Sound Engineer

|

Sylvain Cadars

|

|

Electronics

|

Carlo Laurenzi and Chaya Czernowin

|

| ... | |

Video

The story

Infinite Now is an experience, a state: in the midst of a morass, the presence of an imminent disaster. What is going on, how long, when will it end — all is unclear. It is an existential state of nakedness where the ordinary sense of control and reason are stripped away. This situation is somewhat familiar, we taste it to some degree throughout life, even if the extraordinary does not happen. As the rate of distribution of information grows and as the political situations around us seem more precarious and unpredictable we all get a slight taste of this feeling of naked helplessness. However when war happens or disaster hits something basic changes, as the last remnants of security and routine are taken away. It is an extreme situation, on an existential level. But it holds also an opportunity for an exceptional encounter with the world, bringing its own perspective and long term consequences, historical and personal. In a way, every such a morass is a blockade which stops the evolution of things and might then result in a sudden change. That change is felt in the air and its intuited presence is extremely forceful simultaneously frightening and hopeful.

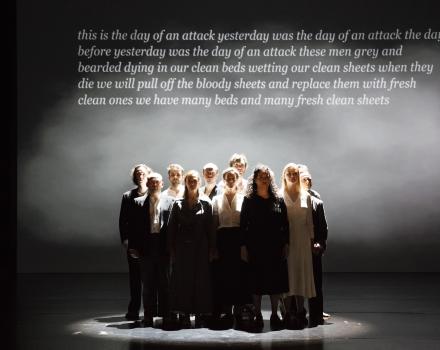

The opera uses texts from two sources: a short story: Homecoming by the celebrated Chinese writer Can Xue, and the play FRONT (Luk Perceval) which is based on All Quiet on the Western Front by Erich Maria Remarque, and on letters of soldiers from the first world war, which were assembled and shaped into a theatre piece by Luk Perceval. Both texts enact a suspension; people are unable to get out of a static situation. In FRONT soldiers are in the trenches, locked in fighting which does not end: they move some kilometres forward only to return back to their former position in a desperate deadly cycle. In Homecoming, a woman thought to pass through a house and continue her journey but then she gradually realizes that it is impossible to leave the house, which is on a cliff above an abyss where a quiet old man serves as an illusionary guide and gives some solace with his presence.

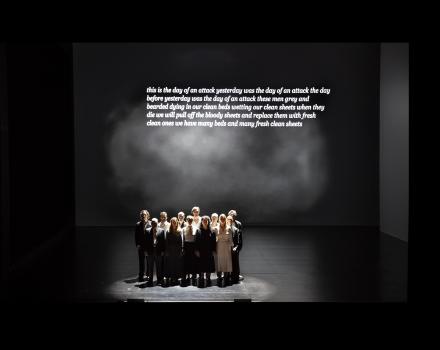

Homecoming with its chaotic internal and external landscape and FRONT with the extended war situation and the various forms of suffering it causes are both testimonies to what I would like to call the wild uncontrolled breathing of the world as it moves closer towards a state of entropy, or towards change, an inevitable change. The deep meaning here is not only historical. The slow merging of two seemingly unconnected worlds gradually creates a kind of an amalgam. This amalgam suggests a state of mind of such difficulty and helplessness, that in order to survive, one must find the will to continue and to find hope in the simplest element of existence, the breathing. As per David Grossmann, “in pain there is breath.” In that sense, while the spoken and sung materials become strong and very visceral and present at the end, they also become further away more like islands in the midst of wind and breathing which slowly cover everything like sand in a sandstorm in the desert.

In this sense, the opera is about more than Homecoming or the first World war. It is about our existence now and here. How we survive, how are destined to survive and how even the smallest element of vitality commends survival and with it perhaps hope.

Chaya Czernowin

Insights

Forgetting the unforgettable

An interview with director Luk Perceval about Infinite Now

Infinite Now is no classical opera. There are no dramatical action, characters, text or music in the classical sense. Can you tell people with no prior knowledge of this opera what type of work it is exactly?

Luk Perceval: I would call it a kind of pandemonium of sounds, voices, fragments of silence. I can only say what it means to me. It is a representation of how the psyche works, namely in an associative, reminiscent manner, falling back on many layers; in the sense that it contains, among other things, elements of WW2 – in short: trauma. But also sounds or fragments associated with nature. It is also a story about longing for death, fear. According to the current state of neuroscience, our mind is wired primarily to detect danger or what is dictated by fear. Yet at the same time, it is about feeling attracted to the unknown. Those elements are integrated into Infinite Now.

To me, these are all elements which, if one was to examine the operation of the mind, emerge and disappear again. What happens from the moment you try to concentrate or try to perceive what silence is? That is what I mean by the pandemonium of silence. Silence in itself does not exist. It is always the sum total of real sounds, on the one hand, and associations with those sounds, on the other hand, as well as of memories evoking sounds and emotions.

Musically, I would say it is an associative space, not exactly an epic story or a melody, but that, for me personally, is music. Because it is meditation in which the music confronts us with the music of life. It is not just about the music which can be perceived, but also about the music you associate with it.

What is it like working with an all-new composition? What effect did this have on directing?

Perceval: The fact that it is created in this way is something I wanted. One thing you always have to deal with as an artist is that the audience is usually served with what it knows, with the canon of the repertory company or the repertory of literature or the opera, as is the case here. As a result, people go to the theatre with certain expectations. I wanted to confront the audience with something completely new, with truly new music. I try to discover what happens during the rehearsals and what impulses are headed my way. It is thus no form of directing one can prepare for – but actually that is something I stopped doing a long time ago.

What is different of course is that as a theatre maker starting from a text you can keep deleting and adapting during the rehearsal process; whereas in the case of Infinite Now, you enter a virtually mathematically pre-given design: There is the score, the music as a fixed given. And that is different because you have to look at the dynamic of that music and what it brings about.

What is the relation between the two text sources, between FRONT and Homecoming?

Perceval: For me, both form one story here. As a spectator, you will always try to understand things the moment you observe them. The moment words are uttered, you start looking for some kind of logic and you ask yourself the question: what is the connection between these two? I still discover every day how it is one story; because it is an expression of the search for the connection between things in the mind – it is about someone who discovers. And in that discovery certain echoes from the past, echoes of the war play a role too. These are echoes which all unite us in Europe – the trauma of war which still reverberates several generations later.

On the other hand, it is a very intense search that all human beings are engaged in: How do I free myself from that, how do I cleanse myself from such a past? What is development at all? Does that mean to forget, to hold back, to experience things? I think you cannot forget things. In that regard, the story of Infinite Now comes down to one thing: it is essentially about searching, letting go of your fear and your past.

What role does music play in this discovery and cleansing process? What significance should be given to this work?

Perceval: I am discovering more and more that Chaya’s score is something extremely introspective and, therefore, very complex at the same time. To me, it is still an adventure, a voyage of discovery of sorts. For Infinite Now, you should cast aside all possible expectations. In the beginning, I called this meditation. I found very inspiring so far is that what she developed requires such great concentration. This work forces us to stop and think and to consciously experience with all of our senses.

This work is something that can be a tremendous provocation, of course. For example, there are very few people who can still sit still. And here, we ask for a totally different attitude, one that I am convinced is necessary in the culture and the times we live in – an attitude which is no longer cultivated and, therefore, goes against the zeitgeist. But I believe that is also why we create art: To go against the zeitgeist. To say: Look what happens if you remove all distractions and need to focus on a new experience. What I find fascinating about it is that there are layers of perception we all have inside us but which may all have been forgotten; that there are things that resonate inside of us, that are present inside us.

Gallery