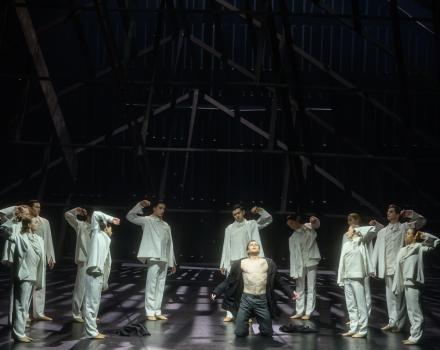

Lamb of God (Dievo Avinėlis) is an opera-ballet set in rural Lithuania in the aftermath of war. It depicts the atmosphere of unease, fear and uncertainty about the future as a village cobbler tries to stick to the straight and narrow path of honesty.

Composed by Feliksas Bajoras in 1982, Lamb of God is based on an eponymous novel by Rimantas Šavelis. 11 March 1990, the Republic of Lithuania was re-established as an independent state, the first Soviet Republic to leave Moscow and leading other states to do so. With a subject that treats the resistance of people in post-war Lithuania, the piece had to wait nearly four decades for its premiere. Lithuanian National Opera and Ballet Theatre, in collaboration with Lithuanian State Symphony Orchestra and maestro Gintaras Rinkevičius and choreographer Martynas Rimeikis, now share this spectacular piece with the world. ‘We all are going to the beyond and will not be able to bring any of our material belongings with us’, says Bajoras, ‘It is crucial to stay spiritually pure.’

Cast

|

Titas

|

Steponas Zonys

|

|---|---|

|

Kvedaras

|

Jeronimas Krivickas

|

|

Apolinaras

|

Kšištof Bondarenko

|

|

Tigrudis

|

Karolis Kašiuba

|

|

Gabija

|

Kamilė Bontè

|

|

Agile

|

Monika Pleškytė

|

|

Mother

|

Jūratė Rudžianskaitė

|

|

Father

|

Alfredas Celiešius

|

|

A woman

|

Ieva Prudnikovaitė

|

|

Anupras

|

Rafailas Karpis

|

|

Paliulis

|

Edgaras Davidovičius

|

|

Morciūnas

|

Tomas Pavilionis

|

|

Naudickas

|

Arūnas Malikėnas

|

|

Kalpokas

|

Egidijus Dauskurdis

|

|

Destroyers

|

Aistis Kavaliauskas

Tomas Kratkovskis

Laimis Roslekas

Igoris Zaripovas

|

|

Orchestra

|

Lithuanian State Symphony Orchestra

|

|

Chorus

|

Chorus of Lithuanian National Opera and Ballet Theatre

|

| ... | |

|

Music

|

Feliksas Bajoras

|

|---|---|

|

Text

|

Rimantas Šavelis

|

|

Conductor

|

Gintaras Rinkevičius

|

|

Director and Choreographer

|

Martynas Rimeikis

|

|

Sets

|

Marijus Jacovskis

|

|

Costumes

|

Elvita Brazdylytė

|

|

Lighting

|

Levas Kleinas

|

|

Chorus master

|

Česlovas Radžiūnas

|

| ... | |

Videos

Story

Act I

The silhouette of a shot man is visible near the wall of the church. This is Kvedaras. Several peasants comment on the night's events. Gabija appears with a mourning ribbon. Apolinaras, who appears unexpectedly, urges Gabija to remarry, because otherwise the authorities will take her home. Here, landless Titas, dreams of a wooden house and his yard. Gabija contemplates her sad fate, but her song is really about Motherland. People and soldiers come and go. Tigrūdis praises Titas for his help. Titas is surprised and angry. After they push each other around, Tigrūdis knocks Titas down and leaves. It is as if the trees are coming alive. They fill the entire space, in which Kvedaras’ dance is a pain-soaked call to battle. Titas is trying to sit up. Trees are pulling him in. Titas frees himself from the temptations of the forest and decides to pursue his life's dream. He walks over to a pile of things that remind him of his parents' house and pulls out a small bench. Suddenly, frightened by Kvedaras’ shadow, Gabija comes running. Titas is confused. Agile is in the cloud of his memory. Gabija leans against Titas’ chest and begins to cry. A candle is burning out.

Act II

A wedding celebration. Titas appears changed beyond recognition, and the guests are already quite drunk. Gabija wears a white dress. She is happy on the outside, but still mourning on the inside. An invisible Kvedaras is sitting at the table. As the noise of the wedding fades, Gabija quietly sings the Farewell Song without anyone noticing, then louder and louder until the anxious guests start looking around. Gabija bursts into tears, a scream escaping her chest. She turns away from the comforting guests and escapes. After an awkward silence, the matchmaker Apolinaras comes to the middle of the circle and tries to ease the situation. But his speech scares the guests, and they disperse. Apolinaras suggests that Titas enter the collective farm, because the partisans need shelter. Titas is lost – is he supposed to give back the land he has just received? Apolinaras walks away and Titas suddenly realises that his home is being turned into a partisan shelter. Tigrūdis appears with destroyers and urges him to join the kolkhoz. Titas still dreams of the future, remembers his parents and his first love, wanders around, carries things from one place to another. He is haunted by the shadows of partisans, destroyers, the autumnal forest and Kvedaras, as a symbol of Death, whose victims are trees. They fall like people.

Act III

A partisan camp. Anupras wears a dirty vest, Gabija is apathetic. Titas is beaten. He remembers images from the past. The partisans' rambling phrases spill over into lamentations about death and the meaning of life. After Gabija's worries about the future of her unborn child but eventually her motherly love prevails, and she decides to give birth. Shots are heard. The battle between the two opposing camps begins. Forest partisans and destroyers are falling. A fire breaks out. Titas hears the voices of the dead. He realises that he will not have his home and throws things into the fire. The dance of flames expands. Kvedaras appears as a symbol of Comfort. The opera ends with the song of the dead rising from the earth, which declares that the Time of Truth has come.

Insights

When two worlds collide

An interview with director and choreographer Martynas Rimeikis

In collaboration with the Lithuanian State Symphony Orchestra led by Maestro Gintaras Rinkevičius, Lithuanian National Opera and Ballet Theatre has taken on the mission of resurrecting Lamb of God (Dievo avinėlis) – a spectacular work by composer Feliksas Bajoras – which has been waiting for its hour for exactly 40 years. Martynas Rimeikis, the director and choreographer of the premiere and artistic director of the ballet company of LNOBT (Lithuanian National Opera and Ballet Theatre), tells us how relevant Lamb of God is today and how the war in Ukraine has changed the creative process.

Asta Lipštaitė: Composer Feliksas Bajoras’ opera Lamb of God, based on the novel of the same name by Rimantas Šavelis, was hailed by Polish musicologist Krzysztof Droba as one of the best operas of the last century. However, this work has been waiting for a full-scale premiere for four decades. Because of the opera’s theme and the libretto, which deals with the most painful topic of our living history – the resistance and the fate of the people in post-war Lithuania – the production of Lamb of God was not allowed during the Soviet era. How did the idea of reviving this work come about?

Martynas Rimeikis: Every national premiere is a huge event in our cultural life. One of the main missions of our theatre is to encourage, promote and nurture national works. The idea of this premiere came from Maestro G. Rinkevičius. We are a national theatre, so it is not only an honour, but also a duty for us to stage works by Lithuanian creators. The work itself, in my opinion, is excellent and really deserves to be performed on stage. It was already appreciated by professionals many years ago, but it has never been staged. I am glad to have had the chance to be involved in this production.

AL: ‘A man who seeks material things does not get them. We will all go to the other world, and we will not take material things there. Therefore, it is better to remain spiritually pure.’ This is how composer F. Bajoras presents the main idea of his work. According to you, what is the most important thing in Lamb of God, and what is your goal as a director in this production?

MR: The work is about the antithesis between material and spiritual life: it is a clash between the visible physical world and the invisible spiritual world. Lamb of God is much more than a struggle between partisans and the so-called ‘defenders of the people’. For me, what makes this work interesting is that it touches on the spiritual world as a special world, with much deeper inner layers beneath the outer layer.

It is always difficult to talk about the details of expression. Sometimes it is very good when a creator knows in detail how everything in his work should look like. Bajoras has a very clear, precise vision of the stage. I follow the semantic and dramaturgical ideas of the composer himself. We work closely together. However, our means of expression and visual plans are slightly different – we are from different generations, we see some things differently.

In all my works, I want the action to take place not so much on the stage, but in the mind and heart of the viewer. This was the principle I followed in Lamb of God. I don’t want to tell and explain, but to let the viewer feel, to inspire his imagination and senses – that’s my creative goal.

AL: Lamb of God is original in terms of genre – after all, opera-ballets are not often staged on our national stage. What are the challenges of directing a double-genre production? And what should the audience expect?

MR: It’s best when the audience expects nothing (laughs). In fact, the fusion of these two genres is not so new. Historically, that’s how ballet started. The opera-ballet Lamb of God is constructed in such a way that there are two forces at work and two storylines: one that takes place in real time, and a parallel one that we don’t see – of people who have departed this life, of the world that is right next to ours. The ballet will reflect that invisible side. The opera will be the setting for the real and living characters. In my mind, I see this work as a single process, with plans that enrich rather than complicate each other.

AL: Although written forty years ago, the work seems more relevant today than ever. The composer F. Bajoras once said: ‘Contemporary opera must communicate what is relevant to today’s man, what comes out of his life, then it can touch people more.’ Has the connection to the current geopolitical context made the work more difficult, or perhaps the opposite?

MR: When the idea of this premiere was conceived, nobody expected a real war threat. I won’t hide the fact that the war in Ukraine has led to some decisions, and some of the ideas and points of view that I wanted to emphasise have changed a bit. I felt that I did not have the right to show and illustrate the pain that people nearby are really experiencing right now, this minute, this second. I found it a bit sacrilegious, so I chose deliberately not to touch on those aspects.

The libretto itself is constructed in such a way that the resistance is more of a circumstance to talk about these two worlds colliding – the material and the spiritual. It is not at the heart of this play. Historical memory is already encoded in us. The immaterial things that we leave behind are much more important – they are the essence.

Adapted from an interview conducted by Asta Lipštaitė.

Gallery