Destined for the convent, the young Manon falls head over heels in love with a handsome stranger and decides to flee with him. Yet aspiring to a life of wealth and luxury, she ends up throwing herself into the arms of a rich nobleman. Can she forget her true love?

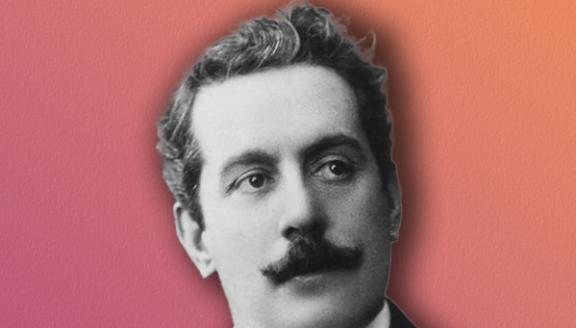

Puccini’s adaptation of the novel by Abbé Prévost had a complicated gestation. An alarmingly long list of librettists succeed each other in trying to satisfy the composer’s demands in terms of dramatic structure and fine verbal detail. Was Puccini struggling perhaps to make his opera sufficiently different from Massenet’s on the same subject? Puccini probably never reached a ‘definitive’ form of this opera but it was his first international success and arguably the first in which the composer found his voice as a musical dramatist. Opera Poznań has entrusted their new production - streamed live on the opening night - to a former winner of the European Opera Directing Prize, Gerard Jones, and conductor Marco Guidarini.

CAST

|

Manon

|

Iwona Sobotka

|

|---|---|

|

Des Grieux

|

Dominik Sutowicz

|

|

Lescaut

|

Jaromir Trafankowski

|

|

Geronte de Ravoir

|

Rafał Korpik

|

|

Edmond

|

Piotr Kalina

|

|

Innkeeper and captain

|

Michał Korzeniowski

|

|

Ballet master

|

Bartłomiej Szczeszek

|

|

Singer

|

Laura Wąsek

|

|

Sergeant

|

Tomasz Mazur

|

|

Lamplighter

|

Marek Szymański

|

|

Orchestra

|

Poznań Opera Orchestra

|

|

Chorus

|

Poznań Opera Chorus

|

| ... | |

|

Music

|

Giacomo Puccini

|

|---|---|

|

Text

|

Luigi Illica

Marco Praga

Domenico Oliva

|

|

Conductor

|

Marco Guidarini

|

|

Director

|

Gerard Jones

|

|

Scenography

|

Blanca Añón

|

|

Light

|

Marc Gonzalo

|

|

Costumes

|

Donna Raphael

|

|

Chorus master

|

Mariusz Otto

|

| ... | |

Video

Story

Act 1

The crowd is having fun, feasting, and flirting. Among the crowd, Edmondo talks about the beauty of love. New people join the feasting – the beautiful Manon Lescaut, accompanied by her brother. The second companion is clearly older. He is Geronte di Revoir, a rich man for whom there are no limits. Des Grieux, who has been mocking love until now, falls head over heels in love with Manon. He learns that the girl is to be locked up in a convent. He can’t bear the thought of it – he begs for a meeting. Manon agrees.

Manon’s brother doesn’t notice when Geronte insidiously orders the host to prepare a cart – he intends to kidnap Manon. Edmondo, who is eavesdropping on him, reveals his evil plan to Des Grieux. When Manon shows up at the appointed time, Des Grieux confesses his love to her, warning her of the danger. He begs her to run away with him. Manon hesitates and finally gives in to the feeling. After their departure, Geronte and Lescaut discover the conspiracy. They do not hurl themselves into a wild pursuit. As Lescaut says: ‘Manon cannot stand poverty…’

Act 2

Manon dresses up in front of the mirror in Geronte’s house. Lescaut observes her parade. Manon withers from a lack of passion, confined in her luxurious cage. She recalls Des Grieux, whom she abandoned. Geronte woos the girl, providing new attractions: beautiful outfits, shows, a ballet master…

After he leaves, to Manon’s surprise, Des Grieux appears, distraught and angered by the betrayal of his beloved. The woman assures him of the constancy of her feelings and begs for forgiveness. Geronte catches them red-handed. The man swears revenge. The lovers must escape. Lescaut warns them of the danger. Manon tries to collect the jewels, ignoring the urging of Des Grieux. Geronte’s soldiers foil an escape attempt. They arrest Manon.

Act 3

Lescaut and Des Grieux bribe a guard. They want to free Manon from prison. The confusion foils their bold plans: the deportation of female prisoners to America begins. The sergeant calls the women one by one, Manon among them. The crowd observing the deportation mocks the prisoners. Lescaut asks the onlookers for mercy, telling them about the tragic fate of his seduced sister.

Des Grieux doesn’t want to let his beloved go. In desperation, he begs the captain to let him on board the ship. The captain agrees – Des Grieux sails with Manon to America as a deckhand.

Act 4

Years pass. Manon loses her strength, suffers, and doesn’t recognize her beloved. He begs her for perseverance. Alone, Manon feels death approaching. She dies unconscious in the arms of Des Grieux, who is in despair.

Insights

Manon Lescaut - the work of many scribes

by Agnieszka Muszyńska-Andrejczyk

The origins of Manon Lescaut’s libretto are as twisted as a winding mountain route. Six or even seven wordsmiths (if you count the composer himself) crafted the opera. Some of them definitely deserve more ownership than others. We will look at each in turn.

The idea for Puccini to set Manon came from Ferdinando Fontana, librettist of two of his early, lesser-known operas. Fontana recommended that the composer read Abbé Prévost's Histoire du Chevalier des Grieux et de Manon Lescaut, commenting: ‘Picture yourself this mixture of elegance and tragedy, which can be musically drawn out of this story with a wave of passion’. The novel itself can be described as a study of the main character's psychological quandaries; it equivocates between the better side of his persona and primal instincts. Des Grieux, an aspiring student of philosophy, a man of ‘benevolent and calm disposition’ becomes the victim of an overwhelming passion. Manon is a femme fatale, inadvertently leading her beloved to financial and moral ruin.

While Prévost's novel is written from a man's point of view, Puccini's Manon Lescaut libretto focuses on the female figure. Some parts of the story are radically changed, others edited. Manon's three suitors melted into one – Geronte. Lescaut, Manon's brother, does not die but from the outset becomes the heroine's guardian. Puccini's Des Grieux has more pathos. Manon is different as well. In Act I, she is an innocent girl whose family is planning to put her in a convent against her will. There is no word in the libretto about the reason for this decision, whereas Prévost spells out bluntly: to tame her ‘predilection for enjoyment’.

Puccini’s idea to use Prévost's story came from Fontana. Tosca had been the same source. Why did the composer decide not to continue to work with the poet who had such brilliant ideas? The reason was quite simple: Fontana was not a man of compromise and was always trying to get his way, ignoring the composer's pleas to make amendments to the libretto. Puccini wrote to his publisher, impresario, friend and advisor Giulio Ricordi: ‘I have found a perfect subject. Manon is a heroine that I believe in and this is why she will conquer the hearts of the audience. No stupid librettist could ever spoil this story – I will definitely like to take part in the construction of the libretto.’ Hard to find a better illustration of the composer's attitude towards the function of the text and the tasks of the librettist. Puccini struggled to put what he required of librettists clearly into words, often driving his collaborators to despair. The composer would also reserve the right to meddle with the libretto until he got his way on a given scene, character or situation. This is why Puccini's Manon has so many ‘fathers’.

In 1889, a tandem of authors began working on Manon Lescaut's libretto in the way which had been current in French theatres for years. Marco Praga delivered the dramatical scheme, scheduled the course of events and their division into acts. Domenico Oliva was assigned the task to give poetic form to this scheme. Misunderstandings between the composer and the librettist led to the departure of first Praga, then Oliva. Ruggero Leoncavallo stepped up for a little while. The composer of Pagliacci was working on the structure of a then second act, which was later totally reshaped. In the final version of the libretto, there were only a few verses left of Leoncavallo’s contribution. Puccini asked his friend to write the libretto while both were staying in Swiss Vacallo, where they worked in adjacent houses. This biographical episode was the reason why some studies have suggested that Leoncavallo's input was greater than it was in reality.

There was stalemate after Praga and Oliva resigned and it was decided that origins of libretto would remain anonymous. Yet another collaborator, Luigi Illica appeared at the beginning of 1892. He was an experienced librettist who worked quickly and effectively. Puccini regarded Illica very highly for the succinctness of phrase and ability to build plot. No wonder that he and Giuseppe Giacosa were commissioned by Puccini to write the librettos of his next three operas: La bohème, Tosca and Madama Butterfly.

Two more people are left to bring up the number of authors to six. Giulio Ricordi was a skilled mediator in conflicts between Puccini and the librettists but has been influential in creative decisions about the opera. He suggested a preface which would explain to the public the narrative shortcuts in the story of two lovers - made in the name of economy. Finally, when Puccini was making amends to the score in 1922; trying to arrive at something resembling the opera's final version, he asked Giuseppe Adami, with whom he was working on Turandot, for a couple of lines. Specifically, he was to complete Manon's famous aria Sola, perduta, abbandonata from the fourth act, overlooked in the earlier versions of the score. The composer wrote: ‘There's an aria in which three or four words repeat over and over. It's necessary to replace them with some different words, full of passion. You will manage that in five minutes. I remember that these repetitions irritated me already a long time ago.’ He also openly admitted that ‘Manon's libretto is by now everybody's and nobody's.’ Adami did what he was asked by adding these lines: ‘Alone, confused, abandoned... / on a desolated plain! Horror! / The sky around me's getting darker!... / Alas, I'm all alone!’

On balance, the libretto of Manon Lescaut belongs mostly to Praga, Olivia and Illica. These three are included in the newer editions of the score – interestingly, always in the alphabetical order, to avoid an inference of hierarchy.

Finally, it is worth stressing that there were risks to Puccini of embarking on the subject of Manon. Jules Massenet’s version had premiered just a few years early and been a spectacular success. Despite that, Puccini was not shy to challenge the French composer, stating that ‘Massenet feels the theme in the French manner, powdered up and in a minuet-esque manner. I, instead, feel it the Italian manner with desperate desire.’ The creative self-assurance beaming from these words had a practical foundation too. Giulio Ricordi, a factotum on Italian and European music markets, managed – in a way known only to himself – to stop the Italian premiere of Massenet's Manon to avoid confrontation and comparisons between operas based on the same literary source. As a result, audiences in Italy watched Puccini's opera first. Massenet had to be patient for his turn…

Gallery