The Marriage of Figaro

When a personal valet hears of the Count’s designs on his fiancé, he resolves to beat his master at his own game. Unfortunately, he has already signed a contract agreeing to marry a spinster, to whom he owes some money.

Mozart’s rip-roaring comedy is a marvel of musical theatre and a must-see show. Full of twists and turns, it is treated with the youthful vigour it deserves in this Royal College of Music production directed by alumnus Sir Thomas Allen.

Cast

|

Count Almaviva

|

Harry Thatcher

|

|---|---|

|

Countess Rosina Almaviva

|

Josephine Goddard

|

|

Susanna

|

Julieth Lozano

|

|

Figaro

|

Adam Maxey

|

|

Cherubino

|

Lauren Joyanne Morris

|

|

Marcellina

|

Katy Thomson

|

|

Bartolo

|

Timothy Edlin

|

|

Basilio

|

Joel Williams

|

|

Don Curzio

|

Samuel Jenkins

|

|

Barbarina

|

Poppy Shotts

|

|

Antonio

|

Conall O’Neill

|

|

Housemaid 1 / Chorus

|

Camilla Harris

|

|

Housemaid 2 / Chorus

|

Jessica Cale

|

|

Wet Nurse

|

Annabel Kennedy

|

|

Head Housekeeper

|

Rebecca Leggett

|

|

Kitchen Maids

|

Alice Ruxandra Bell, Olivia Turner

|

|

Laundry Maid

|

Samantha Gaspe

|

|

Dairy Maid

|

Rebekah Jones

|

|

Gardeners

|

Dafydd Allen, Peter Edge, Conall O’Neill and Humphrey Thompson

|

|

Footmen

|

Peter Dunn and Matthew Keighley

|

|

Head Footman

|

Xavier Hetherington

|

|

Stable Boys

|

Michael Bell and Adam West

|

| ... | |

|

Music

|

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart

|

|---|---|

|

Conductor

|

Michael Rosewell

|

|

Director

|

Sir Thomas Allen

|

|

Sets

|

Lottie Higlett

|

|

Lighting

|

Rory Beaton

|

|

Text

|

Lorenzo Da Ponte

|

| ... | |

Video

The story

Act I

It is the day of Figaro’s marriage to Susanna, maid to the Countess. Figaro, valet to the Count, is assessing the bedroom offered to him by his employer; it conveniently adjoins both the Count’s and the Countess’s apartments. Susanna points out that the room will also be ‘convenient’ when the Count chooses to reinstate the ‘Droit de Seigneur’, a feudal practice in which a local Count can ‘deflower the bride’; a practice that he has recently abolished. Figaro determines to outwit his master.

But Figaro owes money to Marcellina, and has promised to marry her if he does not manage to repay her. He has also raised the ire of Dr. Bartolo, the Countess’s former guardian, for his role in helping bring about the Count’s marriage to the Countess. To complicate matters further, the young page Cherubino wants Susanna to intercede on his behalf with the Count, who has dismissed him from the castle after catching him alone with Antonio’s daughter, Barbarina.

Suddenly the Count shows up, causing disarray. Cherubino hides and hears the Count’s overtures to Susanna. The Count in turn hides, and overhears Basilio, the music master, making insinuations about Cherubino and the Countess. The Count emerges, discovers the unfortunate page, and sends him to rejoin his regiment.

Act II

A weeping Countess laments the loss of the Count’s love. Figaro reveals his plan to outwit the Count: he has sent him an anonymous letter implying that the Countess has a lover. Susanna points out that Marcellina can still invoke the debt and stop the wedding, and a second plan is hatched. Susanna will agree to meet the Count in the garden, but Cherubino will go disguised in her place. Figaro instructs the women to dress Cherubino appropriately.

The page flirts with the ladies by singing his latest composition. When he is half undressed, the Count arrives. Having received Figaro’s letter, he is in a jealous rage. Cherubino, hidden in the closet, knocks over a chair. The Countess, in a panic, pretends that the noise is Susanna, but refuses to unlock the door; meanwhile, Susanna rescues Cherubino, who escapes out of the window. Susanna locks herself in the closet.

The Countess attempts to explain to her husband the presence of Cherubino in her closet. She is as surprised as the Count when it is Susanna who emerges. The two women pretend that the whole episode was a trick to provoke the Count into better treatment of his wife. They confess that the letter was written by Figaro, who then joins them, unaware of the women’s revelations to the Count. When Bartolo, Basilio and Marcellina arrive with a lawsuit to force Figaro’s marriage to Marcellina, the Count is triumphant.

Act III

The Countess and Susanna open the third act with a plan to disrupt the Count’s amorous intentions. Susanna will agree to meet the Count that evening in the garden, but the Countess will go in her place, disguised as her maid.

On the advice of his legal consultant, Don Curzio, the Count insists that Figaro pay Marcellina at once or marry her. Figaro is saved by the timely revelation that he is the long-lost son of Marcellina and Bartolo; everyone but the Count and Don Curzio embraces their new relations.

Finally the wedding celebrations of Figaro and Susanna begin. Cherubino is unmasked among the bridesmaids, but Barbarina shames the Count into allowing him to stay at the castle. Susanna passes the Count the letter dictated by the Countess, confirming her evening rendezvous with him under the pine trees.

Act IV

In the garden everybody is waiting: the Count and Figaro for Susanna; the Countess for the Count; Bartolo and Basilio to witness the revival of the ‘Droit de Seigneur’. Figaro rails against the faithlessness of Susanna, while she looks forward to the conclusion of her plans.

The appearance of Cherubino is potentially disastrous, but the Count arrives and woos ‘Susanna’, in fact his wife. The jealous Figaro is then confronted by Susanna, disguised as the Countess, but he recognises his bride and they are reconciled – witnessed by the Count, who believes he sees his wife in the arms of his valet. He denounces her; the real Countess unmasks herself and forgives her husband. The day ends in celebration.

Insights

Love does conquer

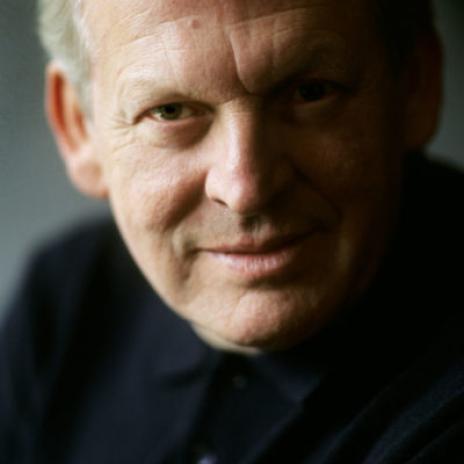

Sir Thomas Allen, famous baritone and director of The Marriage of Figaro, marvels at the richness of the Mozart’s opera.

Amidst the luxuries of Catherine the Great’s Pavlovsk Palace, a beautiful French clock sits atop a marble mantelpiece. The device is the work of inventor Pierre-Augustin Caron de Beaumarchais, and is testament sufficient to a man’s worth and a life well spent. But Beaumarchais was also a playwright, and the man who gave the world… Figaro.

Figaro brilliantly illustrates the depth of life. As the play unfolds, layer after layer is stripped away to reveal the multi-faceted state of a disintegrating society.

Grateful as we undoubtedly are for such a work, this lucky world was further treated when, almost 250 years ago, Beaumarchais’ stage comedy was immortalised in a masterpiece of musical creation. The Marriage of Figaro is the product of a miraculous collaboration between Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart and Lorenzo Da Ponte, one a precocious composer, the other an adventurer in literature.

The opera premiered in Vienna on 1st May 1786. Imagine the atmosphere of the theatre of the day: candles and lamps, a smoky space and then - through the haze - the first scurrying notes of that brilliant overture.

What followed in both play and opera was a story for which the word ‘zeitgeist’ might well have been invented. Lorenzo Da Ponte had taken Beaumarchais’ lead and tapped into the grumbling discontent that was then just emerging, but which would lead inexorably to revolution and chaos.

All that, and comedy too.

Figaro points out the inequalities of its society in a way that is as relevant now as it was then. It deals with the big issues whilst at the same time allowing us to be witness to the finest details of human relations.

There are other details, left unwritten and unsaid, which we must tease out for ourselves in the white, blank spaces between lines. They are there, just as they are in all the greatest works… seek and ye shall find.

Finally, Figaro shows us that love does conquer, though more successfully for some than for others.

I return regularly to renew my acquaintance with Figaro, only to realise with each visit, that I’m learning the work afresh.

Sir Thomas Allen is an established star of the great opera houses of the world and has sung over 50 roles at the Royal Opera House in Covent Garden.

Born in County Durham, he won a place at the Royal College of Music, where he performed the baritone lead in the RCM Opera School production of Arthur Benjamin's Prima Donna. His career began with Welsh National Opera and on his debut he was described as ‘surely the best British lyric baritone singing in opera since the war’.

In the 1989 New Year Honours he was made a Commander of the British Empire, in the 1999 Queen’s Birthday Honours he was made a Knight Bachelor, and in 2013 he received the Queen’s Medal for Music. He is also Chancellor of Durham University. But among his proudest achievements, Sir Thomas can count having a Channel Tunnel locomotive named after him.

Gallery