Orfeo ed Euridice

Orfeo is so consumed with grief at the death of his beloved Euridice that the gods allow him to lead her back from the underworld - if he will not look at her on the way. But who can resist looking at a loved one?

Premiered in 1762, Orfeo ed Euridice is a turning point in the history of opera. Freeing the plot from the conventions of the 18th century opera seria, Gluck introduces fluidity to the drama. The rigid alternation of aria and recitativo is abandoned; continuity and unity are the cornerstones of Gluck's reform. The movement of Gluck’s music - with its lyrical intensity and the interweaving of chorus, solo singing and dance - appeals to choreographers. New National Theatre Tokyo has entrusted their new production to Japanese choreographer and dancer Saburo Teshigawara, known for the beauty and coherence of his productions. Here, he oversees the staging, set, costumes and lighting, with Masato Suzuki conducting the Tokyo Philharmonic Orchestra. In a month that OperaVision dedicates to the Orpheus myth, this stop in Japan is a key marker of the universal power of music. With his most famous aria Che farò senza Euridice enchanting generations, Gluck sets opera on a new path that would ultimately lead to Berlioz and Wagner.

CAST

|

Orfeo

|

Lawrence Zazzo

|

|---|---|

|

Euridice

|

Valda Wilson

|

|

Amore

|

Rie Miyake

|

|

Dancers

|

Rihoko Sato

Alexandre Riabko

Joe Takahashi

Shizuka Sato

|

|

Chorus

|

New National Theatre Chorus

|

|

Orchestra

|

Tokyo Philharmonic Orchestra

|

| ... | |

|

Music

|

Christoph Willibald Gluck

|

|---|---|

|

Text

|

Ranieri de’ Calzabigi

|

|

Conductor

|

Masato Suzuki

|

|

Production / Choreography / Set / Costume / Lighting

|

Saburo Teshigawara

|

|

Artistic collaboration

|

Rihoko Sato

|

|

Chorus master

|

Kyohei Tomihira

|

|

Associate set designer

|

Yoshiharu Tachikawa

|

|

Associate lighting designer

|

Hiroki Shimizu

|

|

Associate costume designer

|

Sonoko Takeda

|

| ... | |

Videos

THE STORY

ACT I

Nymphs and shepherds gather around the tomb to lament in solemn mourning the death of Euridice, who was bitten by a snake. Her husband, Orfeo, laments her loss and can only utter her name (“Ah, se intorno”). Left alone, he reproaches the gods and sings of his grief (“Chiamo il mio ben”). Amore (Cupid) appears to announce that Jove, moved to pity by Orfeo’s despair, will allow him to descend to the underworld to bring Euridice back from the land of the dead. However, there is a condition – that Orfeo is forbidden to look at his wife until they emerge from the caverns of the River Styx otherwise he will lose her forever. Although Orfeo’s blood freezes at the prospect of losing her again, he accepts the condition and, in a clap of thunder, leaves for Hades.

ACT II

At a dreadful cave, furies and spectres appear, trying to deny Orfeo access to the underworld. He begins to play his lyre and his lament eventually placates them and they allow him uninterrupted passage into the Elysian Fields, a beautiful landscape with groves and meadows, rivers and streams. Orfeo is entranced (“Che puro ciel!”) but realises he cannot be happy here unless he is reunited with Euridice. Led by a chorus of heroines, Euridice approaches Orfeo who, without looking at her, leads her away.

ACT III

In a dark cavern on the banks of the Lethe, Orfeo bids Euridice to follow his footsteps. Euridice wonders if she is in a dream and asks Orfeo to explain. He tries to hurry her along, but she is confused and wonders if Orfeo’s love for her has faded like a wilting rose. Orfeo tries to resist turning to look at her, especially when she rails against his coldness, professing she would rather die again than live with him. She expresses her torment (“Che fiero momento!”) and asks why he offers her no comfort. Eventually, Orfeo can take it no more and turns around impulsively to look at her. Euridice dies again. Orfeo, driven to despair, wonders how he can go on living without her (“Che farò senza Euridice?”) and he resolves to kill himself. Amore suddenly appears and disarms him. Moved by his grief, Amore revives Euridice and reunites the couple. At a magnificent temple, Orfeo and Euridice are preceded by nymphs and shepherds who join Amore in celebrating the power of love (“Trionfi Amore”).

Insights

Four keys to Orfeo ed Eurdice by Saburo Teshigawara

1. A drama that develops in a circle

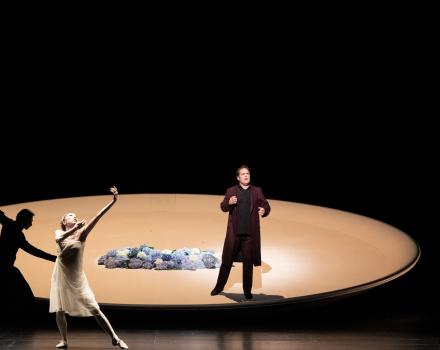

Several choreographers have approached Orfeo ed Euridice in the past, but what I'm interested in is how I can interpret and express this fantastic opera in physical terms. In this opera, the two title roles and Amore, as well as the choir and orchestra, create a special world. In addition, the dancers including Rihoko Sato appear on stage. The set consists of an 8-metre circular platform created in the image of a flower arrangement plate. The singers and dancers perform on this platform, which is decorated with foliage and huge lilies.

The circle is a symbol of fate, nature, rules of law, and the universe. It has an absoluteness which is beyond the reach of human power, and regularity and motility that transcends human knowledge. Momentum and movement are consolidated, absorbed, or diffused into a circle. The circle can easily set off motions. On the other hand, humans cannot be restricted to a circular motion. The human body cannot adhere to absolute rules of law, and this produces various movements as well as discrepancies.

2. Dissonance produces movement

This opera is full of beautiful melodies, but beauty can cause uneasiness. It is not a simple love story. The important factors are the negative emotions such as uneasiness and doubt. Wherein does this darkness lie? Around us, within our body, or in our memory? Furthermore, where can we find this within the music? How can we present this on stage? By expressing different shades of darkness, we can create harmony and dissonance between the musical and the visual elements.

This ‘dissonance between the musical and the visual elements’ is crucial for expression. Such clashes, contradictions and conflicts, or cynical relationships produce the powers of expression. One might sing a sad song in a brightly lit space, or one might sing of joy in near darkness.

What I often do when I create a work is to place two things (that are on different dimensions) on the same table (same dimension), and consider what the gap between them bring about. In other words, I place side by side something physical and non-physical, or something that can be read and cannot be read, and consider the internal contradiction and conflict in the external elements. Such juxtapositions of two heterogeneous things stimulate the heart and the story. What I want is to make everything ‘move’ in dance, opera, or any creative stage work.

3. Universality leads to contemporaneity

I like watching football, and my British friends often describe a fantastic play as ‘classic’ or ‘class’! This doesn't mean it's old-fashioned, but classic in the sense that it has a certain universality. Praising something that transcends time.

I think Europeans are very good at this. When they perform these traditional operas, even though they may give it a new staging, they still try to see the universal aspect in it. This enables them to understand the present.

In contemporary Japan, people tend to focus on specific periods but where is the universality in this? As a citizen of this world, we Japanese should reconsider the importance of ‘universality’. We need to understand that the reason why Japanese traditional culture is respected in Europe or America is because it has a certain universality that is also valid in the modern age. Put differently, we need to question how a new expression can achieve universality.

4. When opera becomes poetry

Something visible and something that is not visible. I want to show something that fades away or something that gradually appears, or in musical terms, something that becomes gradually audible. Rather than just presenting it in an obvious way, I want the audience to recognise more clearly what they have sensed subconsciously. Such process of revelation is at the core of the expressions in my theatre works.

My aim is for ‘opera to become poetry’: poetry itself, rather than something like poetry, or poetry-like something. I want to produce theatrical experiences in which both performers and the audience actively participate and impact each other, and make them feel alive. In this new New National Theatre Tokyo production of Orfeo ed Euridice, with the exceptionally talented musicians and dancers taking part, I believe we can achieve this.

Adapted from an Interview by Miho Morioka

GALLERY