Rigoletto

When a sharp-tongued court jester is cursed for his spiteful words, he is forced to hide his unworldly daughter from his own licentious master.

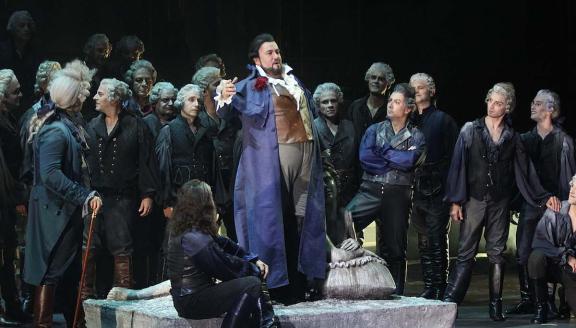

Cannes Film Festival Award winner and frequent Coen brothers collaborator John Turturro directs his first opera in a production that pays homage to his Italian father. Celebrated Verdi baritone George Petean stars in the title role.

In coproduction with the Teatro Regio Torino, the Shaanxi Opera House and the Opéra Royal de Wallonie Liège.

Cast

|

Duke of Mantua

|

Stefan Pop

|

|---|---|

|

Rigoletto

|

George Petean

|

|

Gilda

|

Ruth Iniesta

|

|

Sparafucile

|

Luca Tittoto

|

|

Maddalena

|

Martina Belli

|

|

Giovanna

|

Carlotta Vichi

|

|

Count Monterone

|

Sergio Bologna

|

|

Marullo

|

Paolo Orecchia

|

|

Matteo Borsa

|

Massimiliano Chiarolla

|

|

Count Ceprano

|

Giuseppe Toia

|

|

Countess Ceprano

|

Adriana Calì

|

|

Court Usher

|

Antonio Barbagallo

|

|

Page of the Duchess

|

Emanuela Sgarlata

|

|

Chorus

|

Coro del Teatro Massimo

|

|

Orchestra

|

Orchestra del Teatro Massimo

|

| ... | |

|

Music

|

Giuseppe Verdi

|

|---|---|

|

Conductor

|

Stefano Ranzani

|

|

Director

|

John Turturro

|

|

Sets

|

Francesco Frigeri

|

|

Lighting

|

Alessandro Carletti

|

|

Costumes

|

Marco Piemontese

|

|

Text

|

Francesco Maria Piave

|

|

Project Coordinator

|

Cecilia Ligorio

|

|

Assistant director

|

Benedetto Sicca

|

|

Scene Designer assistant

|

Alessia Colosso

|

|

Costume designer assistant

|

Sara Marcucci

|

|

Subtitles

|

Simone Piraino

|

| ... | |

Video

The story

Act I

The Duke of Mantua is interested in a beautiful girl he has seen in church but at a party in his palace he courts the Countess Ceprano. The humpbacked jester Rigoletto mocks the countess’s husband, who in turn swears revenge. Rigoletto suggests that the Count be arrested or beheaded so that the Duke may do what he will with the Countess. Count Monterone accuses the Duke of seducing his daughter and demands he pay for his crime. After being mocked by Rigoletto, Monterone curses the jester and the Duke before being arrested.

Fearful of the curse, Rigoletto hurries home to check on Gilda, his daughter. On the way, he meets an assassin called Sparafucile, who offers the jester his services. Rigoletto rejects his offer but inquires where he can find him in case he changes his mind. At home, Gilda asks her father about her family background but he gives her no answers. He has hidden her from public all her life and only allows her to leave the house to go to church. Gilda does not even know her father’s name. Before he returns to the palace, Rigoletto warns Giovanna, Gilda’s companion, to keep the door locked at all times. But the Duke has already snuck into the house and realised that the girl from church must be Rigoletto’s daughter. Pretending to be a poor student, he introduces himself to Gilda and professes his love for her. When Giovanna hears footsteps approaching, the Duke escapes through the back door. Still angry at Rigoletto, the courtiers from the party kidnap Gilda, whom they assume be his mistress.

Act II

At his palace, the Duke is upset that his new lover has disappeared. When the courtiers tell him that they have kidnapped Rigoletto’s mistress, he realises that the women they are describing is in fact Gilda and rushes off to find her. Rigoletto demands to know of her whereabouts but the courtiers only mock him. He reveals Gilda as his daughter and begs them to let him see her. Gilda emerges from the room in which she was held captive and throws herself into her father’s arms. Monterone passes by on his way to prison and complains that his curse on the Duke was in vain. Rigoletto swears revenge on the Duke as Gilda pleads for mercy for her lover.

Act III

In order to dissuade his daughter from her love for the Duke, Rigoletto takes Gilda to Sparafucile’s tavern to show her how the Duke is now seducing the assassin’s sister, Maddalena. The jester orders his daughter to disguise herself as a man and prepare to leave for Verona. Rigoletto then commissions Sparafucile to kill the Duke and place his body in a sack for him to collect later.

A thunderstorm approaches and the Duke decides to stay the night. Sparafucile prepares to kill him in his sleep but Maddalena, who is smitten with the Duke, begs her brother to spare his life. As he has already been paid to carry out the assassination, Sparafucile reluctantly agrees to instead kill the next man who comes at the door. Gilda overhears the conversation and decides to sacrifice herself for her lover despite knowing him to be unfaithful. Disguised as instructed by her father, she enters the tavern and is stabbed by Sparafucile. Rigoletto returns to collect the sack containing the Duke’s body. He is satisfied to have his revenge but suddenly hears the voice of the Duke from afar. Rigoletto opens the body bag and finds his daughter, who begs her father for forgiveness as she dies in his arms.

Insights

5 things to know about Rigoletto

1° Laughing at the king

The history of opera – and of the plays on which they’re often based – is inextricably tied to the history of censorship. For most of the last 400 years, composers, librettists and playwrights who have tested the boundaries of morality and taste have had to rewrite their works to get them past official censors.

The main characters in Victor Hugo’s Le Roi s’amuse are the 16th century King Francis I and his jester Triboulet. Despite the three centuries between the action of the play and its first performance in Paris in 1832, the French government banned it after one evening, believing that the insults directed towards Francis I were in fact references to the reigning king, Louis-Philippe I. Hugo brought a lawsuit to permit further performances of the play. This propelled him into celebrity as a defender of freedom of speech in France, though he lost the suit and the play was banned for another 50 years. It was to Le Roi s’amuse that Verdi turned when he received a commission from Venice’s Teatro La Fenice in 1850, as in his words it had ‘a character that is one of the greatest creations in theatre, in any country and in all history.’

2° Immorality and obscene triviality

The composer had faced censorship throughout his career and knew that getting his new opera past the Austrians, who controlled Venice at the time, would be his biggest challenge yet. ‘Use four legs,’ he told his librettist Francesco Maria Piave, ‘run through the town and find me an influential person who can obtain the permission for making Le Roi s'amuse!’ The Secretary of the Teatro La Fenice, Guglielmo Brenna, promised Verdi and Piave that everything would go smoothly. He encouraged the pair to keep working on the opera for the rest of the year but in December the Austrian censor De Gorzkowski vehemently denied consent to the production, calling it ‘a repugnant example of immorality and obscene triviality.’

Piave reworked the libretto, turning the king into a duke and removing the hunchback and the curse from the story altogether. Verdi was against such a radical change and proposed negotiating directly with the censors over each and every one of their complaints. Brenna offered to mediate between the creators and the censors, and by January the parties had reached a compromise: the action would move from France to the defunct Duchy of Mantua; the king would become a duke; a scene in Gilda’s bedroom would be removed; Gilda herself would be killed instead of the duke; and, along with other changes to the names of characters, Triboulet would be called Rigoletto.

3° Woman is fickle

Act III of Rigoletto sees the Duke of Mantua sing one of the most famous tenor arias in all of opera, ‘La donna è mobile’. ‘Can’t live with them, can’t live without them’ is the Duke’s cynical message, who warns that woman’s fickle nature makes her untrustworthy before conceding that no man feels fully happy without a woman’s love.

Verdi knew that he had written a very catchy melody and was desperate for it not to leak onto the streets and canals of Venice before the opening night at the Teatro La Fenice in March 1851. The celebrated Italian tenor Raffaele Mirate was playing the Duke, and Verdi made him swear not to sing or even whistle the tune of ‘La donna è mobile’ except during rehearsals. Not that he had much time to do so – to keep the music secret, Verdi handed the score to Mirate only a few evenings before the première. As for the rest of the cast and the orchestra, the Duke’s aria was revealed to them a few hours before the curtain was due to rise.

The first performance was a triumph and, as Verdi predicted, ‘La donna è mobile’ became an instant hit. It was sung in the streets the next morning, and quickly became a showcase for the tenor voice as well as a barrel organ staple. In more recent times it has taken on a life of its own, appearing as a soundtrack in everything from adverts for tomato paste to the video game Grand Theft Auto.

4° A loving homage

‘I love music,’ says the Italian-American actor, writer and filmmaker John Turturro. A Cannes Film Festival Award winner and frequent Coen brothers collaborator, he directs his first opera with this production. ‘I grew up in a house full of music, listening to Verdi, Puccini and also popular Italian music. Coincidentally, when I was approached for Rigoletto, I was working on a screenplay for a project where Verdi’s music is very present.’

Turturro wants to pay homage to his Apulian father with the opera and has taken his duties as director seriously. ‘I want to do justice to Rigoletto,’ he says, ‘to the material, in a complex and detailed way and not try to bring a conscious modern take on it, but plumb the depths of the piece.’ This has meant working closely with scene designer Francesco Frigeri to create a sense of civilisation in decline, ruined by the bankrupt behaviour of its rulers and citizens. ‘We’ve worked very, very hard on the design to strip it down and avoid anything baroque in our interpretation and our realisation of it. That’s what we hope to do.’

5° An Italian musical adventure

Opera may be Turturro’s present preoccupation, but over the past two decades he has developed a passion for one of Italy’s other great musical legacies. ‘In 1997, I worked with Francesco Rosi on the adaptation of Primo Levi's The Truce. Through Francesco I discovered the work of the dramatist Eduardo de Filippo, and I acted in one of his plays, Questi Fantasmi (These Ghosts), which featured a lot of Neapolitan music. This gave me the idea to direct Passione, a film about Neapolitan music and the city of Naples.’

A year before Passione was released, Turturro took audiences on a haunting, intimate journey around Sicily in the film Rehearsal for a Sicilian Tragedy. Working at the Teatro Massimo in Palermo has allowed the Brooklyn-born star of Barton Fink to return to the island of his maternal grandparents, saying that ‘directing Rigoletto felt like a very natural next step in my Italian musical adventure.’

Gallery