The Turn of the Screw

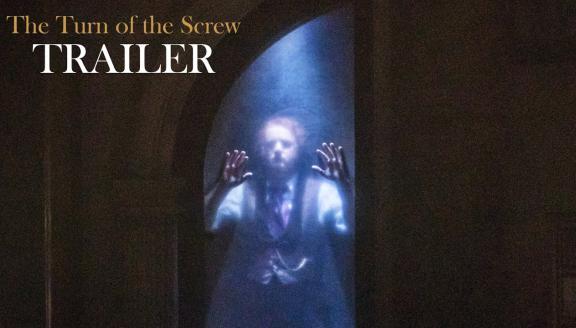

In a remote country house, a governess fights to protect two orphaned children from strange and menacing spirits. But are these apparitions real, or the product of her troubled imagination? And what terrible evil occurred before her arrival?

Based on a ghost story by Henry James, this edge-of-your-seat psychological thriller reaches new levels of terror and claustrophobia in Alessandro Talevi’s spine-chilling production. Britten’s disturbingly beautiful music ratchets the tension up to breaking point.

Cast

|

Prologue / Peter Quint

|

Nicholas Watts

|

|---|---|

|

Governess

|

Sarah Tynan

|

|

Miss Jessel

|

Eleanor Dennis

|

|

Mrs Grose

|

Heather Shipp

|

|

Flora

|

Jennifer Clark

|

|

Miles

|

Tim Gasiorek

|

| ... | |

|

Music

|

Benjamin Britten

|

|---|---|

|

Conductor

|

Leo McFall

|

|

Director

|

Alessandro Talevi

|

|

Lighting

|

Matthew Haskins

|

|

Text

|

Myfanwy Piper

|

|

Set & Costumes designer

|

Madeleine Boyd

|

| ... | |

Video

The story

Act I

A governess has been hired to care for two children at a remote country house by their distant and preoccupied uncle in London. She instantly takes a liking to the children, Flora and Miles, but feels uneasy in the old house. Before long, she has glimpses of a pale-faced, red-haired man in the grounds and at the window. She describes the man to the housekeeper Mrs Grose, who identifies him as Peter Quint, the former valet, who recently died in mysterious circumstances.

The governess vows to protect the children. However, later that day by the lake, she sees another figure and realises it is the ghost of Miss Jessel, the former governess who also died some time previously. That night, the children are lured out into the woods by Quint and Miss Jessel, but the Governess and Mrs Grose arrive just in time to save them.

Act II

The Governess confides in Mrs Grose after more ghostly sightings and is advised to contact the children’s uncle in London. She writes a letter, but the ghost of Peter Quint instructs Miles to steal the letter before it can be posted.

Learning that her letter was never sent, the Governess confronts Miles. As she questions him, Peter Quint’s ghost pressures Miles not to betray him, but he reluctantly names the ghost and suddenly falls dead on the floor. The Governess cries out in grief.

Insights

The Turn of the Screw: Five differences — novella vs. opera

How do you adapt a novella into an opera for the stage, when the author has left it deliberately unclear whether some of the characters actually exist?

1° The role of the narrator

James’s novella consists of three narrative strands. A first nameless narrator begins the tale, relating a strange Christmas gathering where the attendees exchange ghost stories. Attending the Christmas party, the second narrator reads the story of Miles, Flora and the governess from an old manuscript. In a mise en abyme, the fictional Governess herself carries the narrative until the novella’s tragic end.

Britten and librettist Myfanwy Piper, however, removed the first two narrators from the novella and replaced them with a single new narrator. Under the impersonal designation of ‘Prologue’, Britten’s narrator conveys the circumstances that led to the governess’ presence at the Bly country house. From then on, the audience consumes the tale on stage in ‘real-time’.

2° Are the apparitions real?

In James’ novella, the reader’s whole experience of Miss Jessel and Peter Quint is channelled through the governess’ narration of their apparition. In Britten’s opera, the audience can view the visitants directly, as the performers are inevitably physically present on stage. This presence risks reducing the original ambiguity as to whether the apparitions are real or imagined by the Governess.

However, through the Governess’ relation of her experiences to the housekeeper Mrs Grose, the audience still gains insight into her own interpretation of the apparitions’ motives. Mrs Grose retains her function as potential corroborator to the Governess’ version of events. Her inability to see the visitants in both versions of The Turn of the Screw creates doubt as to the Governess’ sanity, so the uncertainty remains.

3° The visitants’ voices

Britten’s decision to create singing roles for the visitants meant Piper had to write many speeches which are non-existent in the novella. While before the visitants were voiceless spectres whose intentions had to be inferred by the reader, here the apparitions openly voice their intentions and address the children directly.

At the beginning of Act II, for instance, Peter Quint and Miss Jessel reappear, quarrelling about who harmed whom first when they were alive and accusing one another of not acting quickly enough to possess the children. This could, again, deplete much of ambiguity of the apparitions’ purpose found in the novella.

4° Nursery rhymes and Latin lines

Much of the opera’s libretto has no basis in Henry James’ text. Britten and Piper’s additions draw inspiration from wide-ranging sources.

• The children’s music finds its sources in nursery rhymes such as ‘Lavender’s Blue’ and ‘Tom, Tom, the Piper’s Son’.

• The lyrics of Miles’ trance-like aria ‘Malo’ are a mnemonic for beginner Latin students, playing on the different meanings of the Latin root: ‘Malo: I would rather be | Malo: in an apple-tree | Malo: than a naughty boy | Malo: In adversity’. This portrays Miles as helpless in the face of the apparitions.

• The line ‘the ceremony of innocence is drowned’, sung repeatedly by Peter Quint and Miss Jessel in Act II Scene I, is taken from W. B. Yeats poem The Second Coming. The violent and prophetic language emphasises the suffering Miles and Flora have faced and suggests that the worst is yet to come.

5° A director keeps us guessing

For many years, critics have disputed whether the apparitions in the novella are real or not. This ambiguity at the heart of The Turn of the Screw can be found in many of Britten’s operas, making the novella particularly suitable for his operatic treatment. Britten and Piper were careful not to interpret the story and impose meaning, but rather to shift the ambiguity of the novella to another medium and leave it to subsequent generations to explore and interpret as they see fit.

In Alessandro Talevi’s acclaimed production, the expressionistic stage is dominated by a huge, skewed window behind which shadowy figures appear. A four-poster bed is ever-present in the centre, which again leaves us to question whether the whole experience may actually be in the Governess’ dreams. Her presence on stage throughout the entire opera heightens the impression that the audience could be seeing through her eyes.

This article is adapted from a piece published on Opera North’s website.

Gallery