Guillaume Tell: freedom for all

Rossini was only 31 when he set foot in Paris. He could already look back on an illustrious career spanning 12 years and over 30 operas. His brilliant, brisk style and dizzying vocal numbers had led him to considerable success in Italy. At the Paris Opera, an audience awaited him that enjoyed this style but was also used to great opera with a prominent choir and long dance interludes. With titles such as Zelmira (Vienna 1822) or Semiramide (Naples 1823), Rossini had already been able to prove his vision of grand opéra. He took the time to familiarize himself with the new circumstances - not least of them the complicated disposition in the house.

In its integral version, the opera lasts five hours and exists in more versions than any other of Rossini's operas. He hustled from rehearsal to rehearsal with frequently changing cast on stage and in the pit, which was usual in that place. It was only in the course of the rehearsals that it became clear which pieces actually made it to the opening and which were dropped. The completely new musical material - the previous Parisian operas were all arrangements of older works - also contains a few folkloristic notes: for instance, the Ranz des Vaches, a folkloristic country dance, finds its way onto the Parisian stage.

Even though it was not close to his heart, Rossini adopted a topical subject: Freedom and the associated struggles of other peoples were absolutely en vogue in Paris a few years before the July Revolution. This is reflected in Rossini's operas written at that time: in Le Siège de Corinthe (1826) the Greeks would rather die than submit to the Ottomans, in Moïse (1827) the Hebrews liberate themselves from Egyptian oppression and move to the promised land. Guillaume Tell (1830), based on Schiller's drama Willhelm Tell, about the Swiss rebelling against Habsburg foreign rule, also fits into this trend. The librettists do not establish a Swiss national myth, but offer the audience an exotic projection surface for their own dreams of freedom; the Alps with their gorges were as alien to Parisian audiences as the Egyptian desert.

Tell is the last opera Rossini composed, even if it was planned quite differently. In 1829 he signed a contract, countersigned by Charles X himself, in which he committed himself exclusively to the Académie Royale de Musique with at least five operas for the next ten years and secured a lucrative monthly pension. In 1830, Tell was thus the first of five planned operas, but shortly afterwards, in the course of the July Revolution, Charles X was overthrown and Rossini's contract thus invalidated. While he fought in court for the observance, i.e. payment of his contract, he himself did not want to break the exclusivity clause contained therein and stopped composing for the time being. When the legal dispute was finally settled in his favour in 1835, Rossini had indeed retired mentally - so this opera was also a release from his professional duties for him.

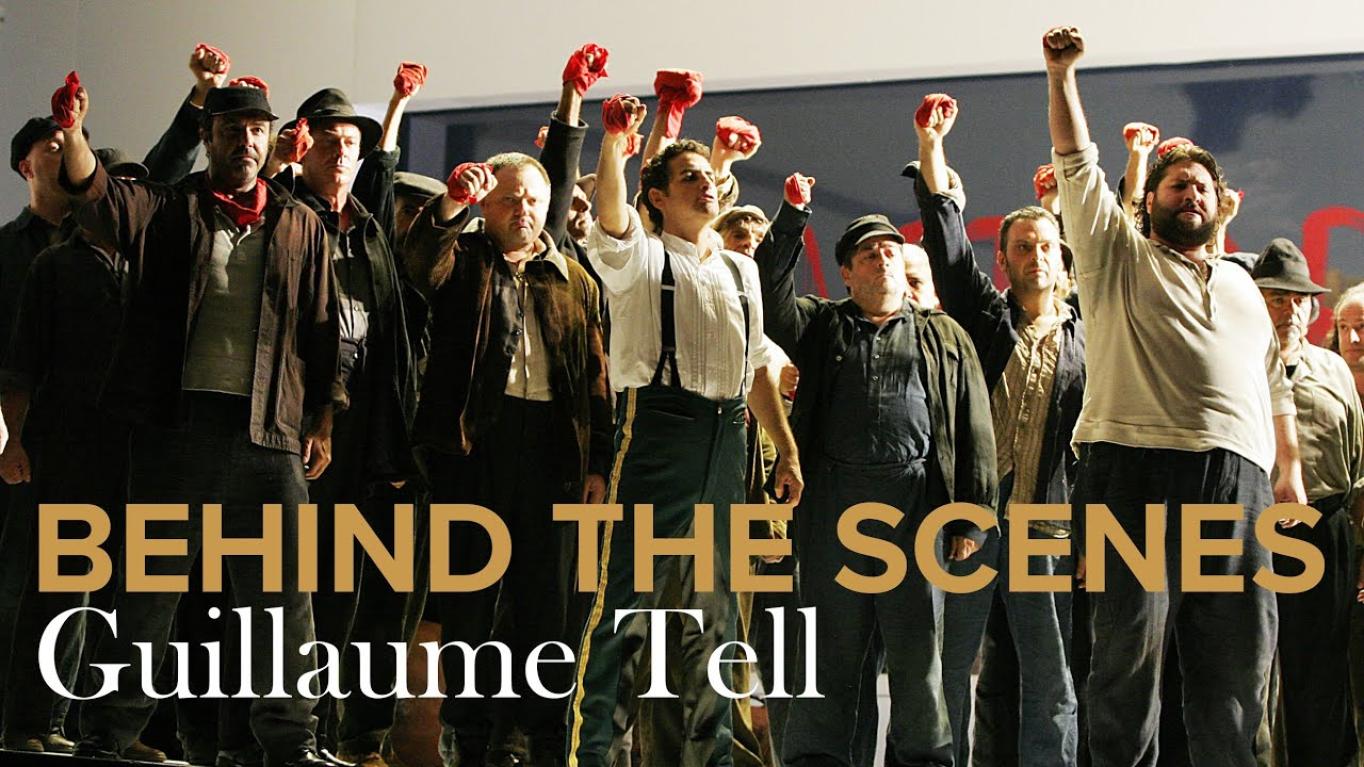

Graham Vick, the director, explains in an interview about the production in Pesaro: Il mio pubblico preferito è popolare [...] Nessuno possiede l'arte (My ideal audience is not elitist [...] Art belongs to no one). In his Tell, he shows the struggle between a rebellious people and a greedy, sadistic clique of oppressors with horse models against the backdrop of snow-covered peaks - rather coincidentally, it seems, they are Swiss against Habsburgs - just as the Paris premiere was not primarily about the setting, but about the principle of a hard-won freedom.

This article is inspired by texts from programme notes of Dr. hc. Reto Müller and Nicholas Payne.