Strauss, Hofmannsthal and Ariadne

The major dualities of life

Bryan Gilliam

After Elektra (1908), Strauss announced that his next opera (Der Rosenkavalier, 1910) would be Mozart: the classical aura of the 1740s set in the Vienna of Maria Theresa. Strauss could well have said that his next opera (Ariadne auf Naxos) would go from the classical to the baroque, especially the French baroque of Lully and Molière, whose Le Bourgeois gentilhomme had so inspired Hugo von Hofmannsthal. Many devotees of Strauss operas hold Ariadne in especially high regard for a host of reasons: the phantasmagorical beauty of a reduced orchestra of some thirty members; the fascinating, seemingly effortless interplay of the serious and the comic; the mixture of vocal forms (coloratura, song, aria, ensembles) and modes of expression (speaking, dancing, solos, trios, quartets, and duos); and the playful allusions to past composers such as Mozart, Schubert and even Corelli.

Equally important is the historical place this work holds in the legacy of the Strauss-Hofmannsthal collaboration, for this work was the central turning point in Hofmannsthal’s journey from playwright to librettist, from spoken theatre set to music (Elektra), to sung play (Der Rosenkavalier), to Hofmannsthal’s determination to write musical text with Ariadne auf Naxos (1912). Hofmannsthal and Strauss wanted to redefine a Gesamtkunstwerk (total work of art) for the twentieth century, one where the divergent art forms work all and severally, each component retaining its integrity.

Hofmannsthal’s criticism of Elektra was that his text was swamped by the music (‘like rich gravy on fine roast beef’). His later self-criticism of Der Rosenkavalier was that there was too much text. That search for a middle ground took the form of Ariadne auf Naxos, initially a theatrical experiment that turned out to be their most prolonged operatic project, spanning some six years. Hofmannsthal believed that from this experiment he could learn how to create a libretto where musical numbers regain their ‘paramount importance’.

The model for a modern Gesamtkunstwerk was to be found in neither German music drama nor the nineteenth century, for that matter, but in the French baroque, more specifically the comédie-ballet, which included singing, dance and the spoken word. Strauss, too, was eager to get away from the aura of Bayreuth and Wagner’s notions of music as a metaphysical, redemptive healing space, and he followed Hofmannsthal’s lead, though at first not enthusiastically. The poet’s plan was to construct a divertissement at the end of a truncated version of Molière’s play Le Bourgeois gentilhomme, where five acts became two and instead of the final ‘Turkish ceremony’ there would be an ‘opera’. The original contours of their opera seemed simple enough: two opposing worlds – seria and commedia – both in the spirit of Molière. The opera libretto provided ample opportunities for dance, solos, duets, trios, even a quintet. Hofmannsthal encouraged Strauss to express himself on a reduced (i.e. non-Wagnerian) scale.

Strauss quickly threw himself into the work, complete with incidental music for the play and six numbers for the opera:

1. Double aria for Ariadne (‘Ein schönes war’/ ‘Es gibt ein Reich’)

2. Harlekin’s Song (‘Lieben, Hassen’)

3. Zerbinetta’s coloratura aria (‘Grossmächtige Prinzessin’)

4. Male buffo quartet + Zerbinetta

5. Male buffo trio

6. Finale (Ariadne and Bacchus)

It premiered in 1912 and was, simply put, a flop: the audience found neither play nor opera possible to relate to in any meaningful sense, and expectations were high after the success of Der Rosenkavalier. Poet and composer rightly ditched the play and instead created a chatty Prologue rich with behind-the-scenes jokes and a light ‘tutorial’ on the meaning of the opera to follow. This revised work (Prologue and Opera) of four years later was a success, and is now nearly always performed in this way.

On the surface the opera would seem to be about the classic pairing of Bacchus and Ariadne, immortalised in Titian’s great painting, but Strauss was not fond of tenors and, although he did not cut Bacchus from the score, he made it more about an opera concerning the major dualities of life from A to Z, from Ariadne to Zerbinetta: fidelity–promiscuity, eternal–momentary, transcendence–illusion, negation–acceptance. A third and shorter leg of this triangle is the Composer, a mezzo, who creates the Ariadne opera but who also(momentarily) falls in love with Zerbinetta.

(Painting) Bacchus and Ariadne – Titian, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

But Ariadne, not Zerbinetta, is the major character, and her importance is underscored by an incident in real life: Hofmannsthal had a life-model for Ariadne named Ottonie von Degenfeld, a Countess whose husband – Count Christoph-Martin von Degenfeld – died just two months before the Countess gave birth to their daughter Marie-Therèse. The Countess had a nervous breakdown and, like Ariadne at the beginning of the opera, was hardly able to speak or walk. Hofmannsthal met her in this state and brought her out of the bonds of mental illness through visits, reading and letters (which were published in English in 2000). Hofmannsthal urged her to live on: ‘The harlequin sings it better than I can express it in words.’

You must lift yourself from darkness,

Even if to newer pain!

You must live, for dear life,

Live again this one time.

Most important for the history of the Strauss-Hofmannsthal relationship is the fact that, with Ariadne, the poet was no longer writing plays to be set to music, such as Elektra and Rosenkavalier, but was now, for the first time, writing a libretto with the musical opportunities embedded in the text itself. It marked a new beginning for their collaboration where Hofmannsthal developed a degree of trust in the composer, allowing him to create spaces for Strauss’s music. Even the chatty Prologue ends with a full-blown aria for the Composer: ‘Musik ist eine heilige Kunst’ (Music is a holy art).

Hofmannsthal referred to his librettos as a scaffold for music, and in this work it contains three parts:

1. Ariadne

2. Zerbinetta (and her friends)

3. Ariadne and Bacchus

Part 1 is dominated by strings, mostly in the minor, and in slow to moderate tempi. Part 2 is wind oriented, allegro, and in the cheerful major, while part 3 is for full orchestra and a mixture of all the above. Part 1 is built around two Ariadne arias (‘Ein schönes war’ and ‘Es gibt ein Reich’), while part 2 centres on Zerbinetta’s grand coloratura aria, ‘Grossmächtige Prinzessin’. The final part is a grand duo between Ariadne and Bacchus on a broad, almost Wagnerian scale.

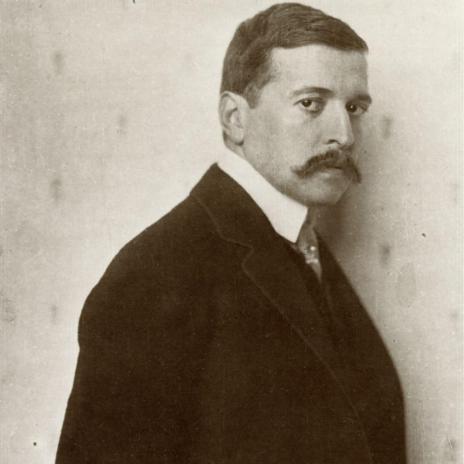

(Photo: Hugo von Hofmannsthal in 1910)

But what Hofmannsthal offered Strauss was far more than a scaffold; though the composer did not understand at first, so the poet explained:

What Ariadne is all about is one of the straightforward and stupendous problems of life: fidelity; whether to hold fast to that which is lost, to cling to it even in death – or to live, to live on, to get through with it, to transform oneself, to sacrifice the integrity of the soul and yet in this transmutation to preserve one’s essence, to remain a human being and not to sink to the level of beast, which is without recollection.

Thus the central focus of the opera was on fidelity and the importance of rising beyond one’s present self, yet in that process preserving one’s inner essence. Such a dialectical problem, the paradox of forgetting while remembering, could be solved only by the act of transformation. As Ariadne is given godly status alongside Bacchus, they both attain, paradoxically, a deeper sense of humanity. This overarching theme, which remained vital to Strauss throughout his artistic life, from Death and Transfiguration (1890) to the Metamorphosen (1945), resonated deeply with the composer.

Bryan Gilliam, Professor Emeritus at Duke University (USA)