A Valentine card to Bernstein’s Candide

In 1953, the well-known playwright Lillian Hellman suggested to Leonard Bernstein that he adapt Voltaire's Candide for music theatre. Voltaire's 1759 novella satirised the popular philosophies of his time and specifically targeted the Catholic Church, whose Inquisition tortured alleged heretics to death in the infamous event known as Auto da fé, (Portuguese for ‘act of faith’). Observing an uncanny resemblance between the hypocrisy and violence of the Inquisition purges and the tactics used by the House Un-American Activities Committee, fueled by anti-Communist propaganda, Hellman delighting in the idea of drawing parallels between Voltaire’s biting satire and current US politics.

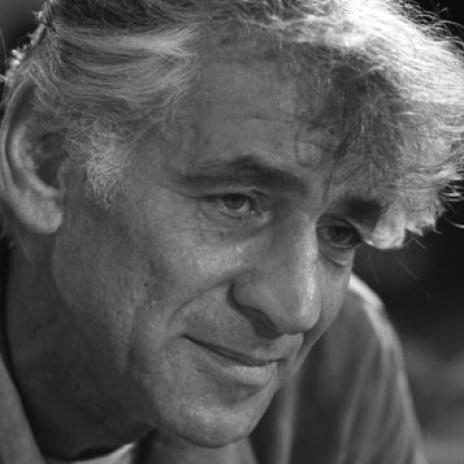

‘That was the time of the Hollywood Blacklist…television censorship, lost jobs, suicides, expatriation and the denial of passports to anyone even suspected of having once known a suspected communist. I can vouch for this; I was denied a passport by my own government. By the way, so was Voltaire… His answer was satire, ridicule and, through laughter, to provoke in his reader self-recognition and, of course, self-justification: ‘Who, me? Not me.’ Which produces discussion, makes debate—and debate is, after all, the cornerstone of democracy. So Lillian and I were naturally magnetized by Voltaire’s…wit and wisdom, and quickly set about our work…’

– Bernstein in the notes for a 1989 concert version of Candide

Hellman started work on the libretto, helped by the poet John Latouche and Bernstein himself, who wrote numerous musical sketches. Soon the poet Richard Wilbur replaced Latouche. Hellman, Bernstein and Wilbur worked together regularly until 1956, with Bernstein simultaneously composing West Side Story. In October of that year, Candide was ready to be performed in Boston, where the poet and writer Dorothy Parker contributed lyrics to The Gavotte of Venice, while Bernstein and Hellman supplemented their own lyrics to other numbers. The list of illustrious lyricists was getting longer and longer.

Candide first opened on Broadway as a musical on 1 December 1956. The premiere production was directed by Tyrone Guthrie and conducted by Samuel Krachmalnick. Ironically, it is the very attitude of speaking truth to power, which first attracted Hellman and Bernstein to the project, that threatened the performance. Guthrie was particularly apprehensive of the ‘Auto da Fé’ scene with its unashamed mockery of the House Un-American Activities Committee. Would the urgent political impulse for the musical’s creation pass the test of time?

When one has something unpleasant to say, one should always be quite candid.

Even though Candide sparkles with ideas, its heavy agenda weighed it down. If the build-up to its premiere was extensive, the work on its numerous revisions thereafter took longer. Considered one of the most laboured over Broadway shows in history, it endured many incarnations before Bernstein created what he called the ‘Final Revised Version’. He presented it with the London Symphony, which he presided over, at the Barbican in December 1989.

What, then, does remain of Bernstein’s witty, fast-paced interpretation of Voltaire’s satire? Despite eradicating all hope with its glaring portrait of moral corruption and natural catastrophes, Candide inexplicably leaves the listener in a buoyant mood. Conceived as a ‘Valentine card to European music’, the score teems with references to various dance forms such as the gavotte, waltz and polka and is interlaced with bel canto arias, Gilbert and Sullivan-type comedy, grand opera and what Bernstein called ‘Jewish tango.’ Bernstein’s ability to explore the depths of human depravity so irreverently and lightheartedly shows every sign of a stroke of genius. Starting with the overture’s crystal clear wit by way of the sarcastic ‘Auto-da-fé (What a Day)’, Bernstein comes full circle with the finale ‘Make our Garden Grow’. Granted, in the context of the story, any utopia is suspicious and exposed as a sham. Standing alone, however, the listener can indulge in a moment of sincere optimism. No longer is it the optimism of innocence, it is the stance of one who dares to hope in spite of all odds.

We're neither pure, nor wise, nor goodWe'll do the best we know.We'll build our house and chop our woodAnd make our garden grow.