When a beautiful young woman in rural Moravia becomes unexpectedly pregnant, she learns that love is sometimes only skin-deep.

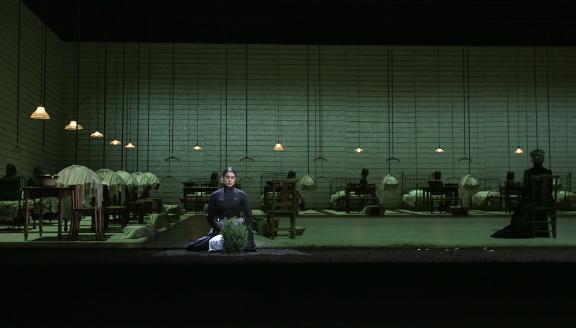

Asmik Grigorian as Jenůfa in her Covent Garden debut and Karita Mattila as the Kostelnička lead a star cast with Hungarian conductor Henrik Nánási conducting a stunning score infused with traditional folk melodies of Janáček’s native Moravia. Claus Guth’s acclaimed staging - both elegant and open while being utterly claustrophobic and oppressive - captures the great humanity at the heart of the opera.

Cast

|

Jenůfa

|

Asmik Grigorian

|

|---|---|

|

Kostelnička Buryjovka

|

Karita Mattila

|

|

Laca Klemeň

|

Nicky Spence

|

|

Števa Buryja

|

Saimir Pirgu

|

|

Grandmother Buryjovka

|

Elena Zilio

|

|

Foreman

|

David Stout

|

|

Mayor

|

Jeremy White

|

|

Mayor's Wife

|

Helene Schneiderman

|

|

Karolka

|

Jacquelyn Stucker

|

|

Herdswoman

|

Angela Simkin

|

|

Barena

|

April Koyejo-Audiger

|

|

Jano

|

Yaritza Véliz

|

|

Chorus

|

Royal Opera Chorus

|

|

Orchestra

|

Orchestra of the Royal Opera House

|

| ... | |

|

Music

|

Leoš Janáček

|

|---|---|

|

Conductor

|

Henrik Nánási

|

|

Director

|

Claus Guth

|

|

Sets

|

Michael Levine

|

|

Lighting

|

James Farncombe

|

|

Costumes

|

Gesine Völlm

|

|

Text

|

Leoš Janáček

|

|

Concert Master

|

Vasko Vassilev

|

| ... | |

Video

The story

Jenůfa is keeping secret from everyone that she is pregnant by Števa, who drinks and is a womaniser. Jenůfa’s stepmother, the Kostelnička, had a violent, alcoholic husband and tells Števa he won’t be allowed to marry Jenůfa unless he stays sober for a year. Števa’s overbearing behaviour towards Jenůfa angers Laca, who loves Jenůfa and is jealous. When Jenůfa defends Števa, Laca becomes enraged. They struggle and he slashes her face with a knife.

Months later, the Kostelnička and Jenůfa conspire to keep the birth of Jenůfa’s illegitimate baby secret. Števa knows he has a son, but refuses to marry Jenůfa now her face is disfigured. Laca offers to save Jenůfa’s reputation and marry her, but is reluctant to take on Števa’s child. The Kostelnička tells both Laca and Jenůfa that the baby died while Jenůfa slept. But on Jenůfa’s wedding day the truth is revealed.

Insights

A Universal Story

Jenůfa Director Claus Guth in conversation with Dramaturg Yvonne Gebauer

(Abridged from a fuller discussion, featured in the Royal Opera House production programme)

Yvonne Gebauer: You’ve directed just over a hundred operas, but none by Janáček before. What interests you about his music?

Claus Guth: Janáček’s style is minimalistic in that it articulates only what is necessary to produce the maximum emotion. This strikes me as very modern, very contemporary. I am also hugely interested in Janáček’s extensive use – in his setting of the text as well as in the music itself – of insistence and repetition, forever ratcheting up the tension. That completely subverts the cliché that his works are purely naturalistic representations of reality.

YG: How are we to understand Jenůfa? Is it a Milieustück – a drama about a specific community?

CG: During the rehearsal process, again and again we noticed that singers as well as members of the production team came up against themes they recognized from their own lives, a particularly striking example being the kind of repetitive impulse that’s seen in certain family histories. Once a problem or a failing has manifested itself, it seems inescapable that the same problem will be passed on from generation to generation, like a family curse. It’s as though all the force and frenzy we apply to blocking it actually summon it into being. It’s an interesting notion, and one that’s deeply rooted in this opera.

For all our metropolitan, liberal and enlightened views, we are continually forced up against the fact that – irrespective of the direction we later take – we are shaped by a pre-existing moral code which tells us what is right and wrong and how we should live our lives. Jenůfa illustrates how huge social pressure to conform can bring about the complete downfall of an outsider, someone who stands outside the norm. The figure of the Kostelnička is a case in point. Because a lot went wrong for her in her earlier life, she tries to overfulfil the rules, even committing murder in the process.

YG: So you could say that, while telling a very clear and realistic story, the opera also functions as a parable, looking outside and beyond itself.

CG: That is the core of our interpretation. While appreciating the mood and music of the opera, we also want audiences to realize the universality of the story.

YG: Gabriela Preissová’s novel Její pastorkyňa (Her Stepdaughter) inspired Janáček’s Jenůfa. What does it tell us about the Kostelnička’s back story?

CG: As a young woman, the Kostelnička had great hopes for the future. She was highly intelligent and always stood out from the crowd. At some point she fell in love with Tóma, Buryjovka’s son, and was utterly convinced that, through him, her life would derive lasting joy and meaning. But her hopes were to be bitterly disappointed, when Tóma married another woman, with whom he had a child. After his wife’s death, the Kostelnička became stepmother to the child and second wife to Tóma, an inveterate drunkard who squandered all her money before finally perishing in an accident.

After being given the office of sacristan (Kostelnička), she grew into an unimpeachable moral authority in the village. Her main purpose in life at the time the opera opens is to save her stepdaughter from making the same mistakes she herself made. But Jenůfa has fallen in love with Števa and history starts to repeat itself…

YG: How is Jenůfa shown to be an outsider in the opera?

CG: From the very outset, she refuses to accept the prevailing rules, for example by not following the daily rhythm of work, or by busying herself with intellectual matters, or teaching Jana to read and write. There’s a definite sense that Jenůfa is ready to move in the direction of a new kind of society.

YG: What is the role of the stage design in this production of Jenůfa?

CG: When you look at the work closely, it’s clear that each act – while depicting the changing of the seasons – also has its own musical language as well as its own defined theme. This can in part be explained by the fact that the composition of Acts I and II were separated by several years. From this came our decision to create a distinct atmosphere for each of the acts.

Of foremost importance for us in Act I was how to represent Janáček’s persistent musical motif of the millwheel. This we’ve chosen to interpret not literally but metaphorically, as the millwheel of the system, the endless repetition and unchanging uniformity of everyday life. It’s a system that is ritualized and rigidly structured. But the moment a cog stops turning in a system like this, everything comes to a standstill. This broken cog is Jenůfa.

Our stage design depicts a microcosm, completely enclosed by walls. This world contains everything that makes up the everyday experience: a bed for sleeping, a table for eating, a uniform for work and so on. Outside these walls is the unknown Other, an impossible place, one for maybe escaping to one day. We’ve sought to encapsulate ideas like these in the closing tableau, where the way to another world opens up for Jenůfa and Laca – bringing with it a break with the former system.

Gallery