The story intertwines themes of war, revenge and love between two unknowingly estranged brothers, the Comte de Luna and the troubadour Manrique, who both love Léonore. Raised by the gypsy Azucena, Manrique becomes part of her quest to avenge her mother’s death at the hands of Luna’s father, a revenge rooted in mistaken identity. Can the true family bonds be revealed in time before blood is spilled?

When Verdi first read García Gutiérrez's play El trovador, it was the strong situations and the characters, especially the gypsy Azucena, that fired his imagination: he saw in the bizarre plot and the insane passions of the protagonists a pretext for more operatic boldness along the lines of Rigoletto. The collaboration between Verdi and his librettist Cammarano was a happy one; so, all the more sad then, that the latter died in July 1852, when composition was still at an early stage. The success of the premiere in 1853 in Rome surpassed even that of Rigoletto, and the speed with which Il trovatore swept the world, literally from Scotland to the South Pacific, was even more sensational. In 1856, Verdi was commissioned to adapt Il trovatore for the Paris Opéra by adding an extended ballet to Act III. Making other musical revisions, Verdi himself conducted the premiere in January 1857 and it is the version which is a highlight at this year’s Wexford Festival Opera, Ireland’s home for the rediscovery of the more rarely staged corners of the operatic repertoire.

CAST

|

Manrique

|

Eduardo Niave

|

|---|---|

|

Léonore

|

Lydia Grindatto

|

|

Fernand

|

Luca Gallo

|

|

Inés

|

Jade Phoenix

|

|

A messenger

|

Vladimir Sima

|

|

Le Comte de Luna

|

Giorgi Lomiseli

|

|

Azucena

|

Kseniia Nikolaieva

|

|

Ruiz

|

Conor Prendiville

|

|

Un vieux Bohémien

|

Philip Kalmanovitch

|

|

A jailer

|

Conor Cooper

|

|

Dancers

|

Luisa Baldinetti

Andrea Carlotta Pelaia

Miryam Tomé

|

|

Orchestra

|

Wexford Festival Opera Orchestra

|

|

Chorus

|

Chorus of Wexford Festival Opera

|

| ... | |

|

Music

|

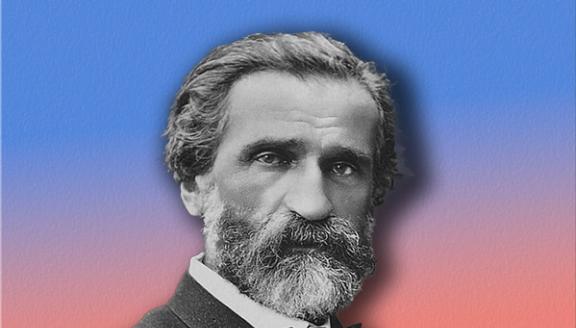

Giuseppe Verdi

|

|---|---|

|

Text

|

Salvatore Cammarano

Leone Emanuele Bardare

|

|

Director

|

Ben Barnes

|

|

Conductor

|

Marcus Bosch

|

|

Sets

|

Liam Doona

|

|

Costumes

|

Mattie Ullrich

|

|

Movement director

|

Libby Seward

|

|

Co-lights

|

Danile Naldi

Paolo Bonapace

|

|

Projections

|

Arnim Friess

|

|

Chorus master

|

Andrew Synnott

|

| ... | |

VIDEOS

STORY

Act I

The Duel. In the prologue, Fernand, the Count’s right-arm man, tells the background: the Count of Luna (father) has burned a gypsy woman at the stake, accused of having cast the evil eye on one of his children. The gypsy’s daughter, who witnesses the execution, vows to avenge her mother. She then kidnaps the Count’s youngest son. Some child’s bones are found in the same place where the gypsy woman had been burned. We move to the gardens of the palace of Léonore, the protagonist with whom the surviving son, the Count of Luna (son) is secretly in love. Unfortunately for him, Léonore does not reciprocate his affection and, indeed, we know from the confession she makes to her lady-in-waiting (Inès), that her heart is forever destined for a mysterious troubadour, who sings a song every evening under her window. The young man had distinguished himself in a knights’ tournament, and is therefore doubly rival of the Count (son). In fact, when one night, overcome by passion, the Count (son) goes to Léonore’s garden, the young woman throws herself into his arms, mistaking him for the troubadour. When the troubadour arrives and sees the scene, he immediately thinks of betrayal. But a ray of moonlight illuminates the scene: Léonore, asks the troubadour forforgiveness, calling him by his name: Manrique. The Count (son) then understands that his rival is also an enemy of the State (Manrique has been sentenced to death). The two challenge each other to a duel.

Act II

The Gypsy Woman. We then move to the gypsy camp. While everyone else is singing happily, only Azucena is haunted by her ghosts. We discover other details of the story told by Fernand at the beginning: Azucenza is the daughter of the gypsy burned by the Count (father). She, out of revenge, kidnapped one of the two children, planning to throw him into the fire. Alone, either because of haste or distraction, she throws her son into the flames instead of the kidnapped child. When she sees the Count’s child still alive and kicking, he decides to raise him without revealing the child’s true identity to anyone. Here the audience (but not Manrique, who has heard the same story we did) understands everything: Manrique is the Count’s (son’s) brother. And in fact he himself says that, in the duel, he spared the Count’s (son’s) life, following a divine impulse... Ruiz, Manrique’s trusted friend, arrives and warns that the city of Castellor has under siege. Manrique, although wounded, leaves, and arrives just in time to foil the Count’s (son’s) plan to kidnap Léonore.

Act III

The Son of the Gypsy. In the meantime, Fernand captures Azucena and recognizes her as the gypsy’s daughter. Azucena asks Manrique for help, and at that name the Count (son) rejoices: the mother of his sworn enemy is in his hands! Manrique and Léonore, who are about to get married, are interrupted by the news that Azucena is about to be thrown on the stake. Manrique leaves to save her.

Act IV

The Revenge. The Count (son) has reconquered Castellor and captured Manrique, who is now waiting in prison with his mother. Only Léonore, who has escaped capture, tries everything to save him as soon as she sees the Count (son). She will give herself to the Count (son) if Manrique is spared his life. The Count (son) accepts, but he does not know that the girl has drunk the poison hidden in her ring (very romantic, isn’t it?). Dying, she enters Manrique’s cell, explains her plan to him and finally dies in his arms. Unfortunately, the Count (son) has heard everything and understands the betrayal plotted by Léonore. He then decides to immediately send Manrique, his sworn enemy, to the gallows. When it is too late to stop him, Azucena reveals to the Count (son) that Manrique is none other than the brother believed to be dead: Azucena declares the revenge she swore in front of her mother accomplished!

Insights

Blowing the dust from our souls

Director, Ben Barnes

‘There is no past or future in art. If a work of art cannot live always in the present, it must not be considered at all.’

Pablo Picasso

Picasso’s words might be a mantra for those of us engaged in opera production. The backdrop against which the story of Le trouvère unfolds is an obscure Spanish civil war lost in the mists of late medieval history. If it means anything to anybody now it is probably a handful of academics specialising in the history of the Iberian peninsula in the 15th century. With Picasso’s prescription in mind, our decision to bring the action forward to the time of the 1936-39 civil war in Spain is motivated by several factors. Operatic stories tend to be complex and convoluted and none more so than Le trouvère. How often have you sat dutifully reading your programme synopsis with well-intentioned focus, only to give up halfway through and abandon yourself to muddling along as best you can as the action unfolds? Well, by bringing the action forward to an event we know from film, from newsreel and from literature you are, at the very least, being provided with coordinates which you will recognise.

And so, we suggest that the two opposing factions in this telling of Verdi’s opera equate to the conservative, nationalist, Catholic forces led by the general, Franco on the one hand and on the other the opposing multi-national militias dedicated to the preservation of democracy and upholding the status quo of the Second Republic. Having opted for this scenario it is easy to see where the two male protagonists most comfortably fit. Le Comte de Luna with his swagger and arrogance, his righteous anger and entitlement, his single mindedness and corrosive egotism has all the qualities required of the fascist leader determined to bend people to his will. And the opposing force, led by the dreamer troubador, Manrique, are of Spanish and overseas militias dedicated to preserving the rights of the ordinary working man and made up of romantic, committed young people driven by idealism but more often than not outmanoeuvred by their more calculating and better organised opponents. And so it is that Le Comte de Luna prevails although his victory is a pyrrhic one - he wins the fight but loses the girl - and the doomed Manrique is left, as Auden would have it to ‘sing of human unsuccess, in a rapture of distress’.

These character traits are manifest in the two male protagonists’ motivations in the central duel of the opera, that which takes place over the wooing and winning of Léonore. Luna by his own admission is motivated by jealousy, rage and lust and Manrique by a sublime but ultimately ill-fated romantic love. And it is this deadly rivalry which foregrounds the opera and gives rise to the rich and glorious music and melodies with which Verdi imbues it. So, in fact, the Spanish war is just a backdrop to the playing out of the battle between Luna and Manrique for the love of the opera’s heroine, Léonore. In this light any chosen war setting is little more than window dressing. The real war is over the woman and in that regard we recall the Trojan war fought over Helen of Troy of whom the playwright Christopher Marlowe coined the phrase ‘the face that launched a thousand ships / And burnt the top-less towers of Ilium’. The sexual longing attributed to Faustus in respect of Helen by Marlowe might equally apply to the Comte de Luna in his quest for Léonore.

And notwithstanding all the foregoing the real story lies in that elemental heady space of myth and legend in a meta-narrative of infanticide and fratricide and encompassing along the way love, retribution, suicide and death. The load baring of the mythical in the opera is carried by the fabulous figure of Azucena driven by a fierce love of her surrogate son, Manrique, pouring into him all the love for the son she has lost by her own hand and driven too by an insatiable thirst for revenge on the son of the man who was responsible for her own mother’s agonising death. From the opening bars of her entry into the opera - ‘la fiamme brille...’ to her triumphant concluding, ‘le ciel avengé ma mère’ it is Azucena who drives the story to its pre-ordained and tragic denouement with three of its four main characters dead and the fourth, the Count de Luna, the unwitting architect of such destruction left with a victory that is no victory at all. It takes the musical genius of Verdi to bring these elemental themes to blazing life and like all good art it blows the dust from our souls. Enjoy.

GALLERY