L'Orfeo

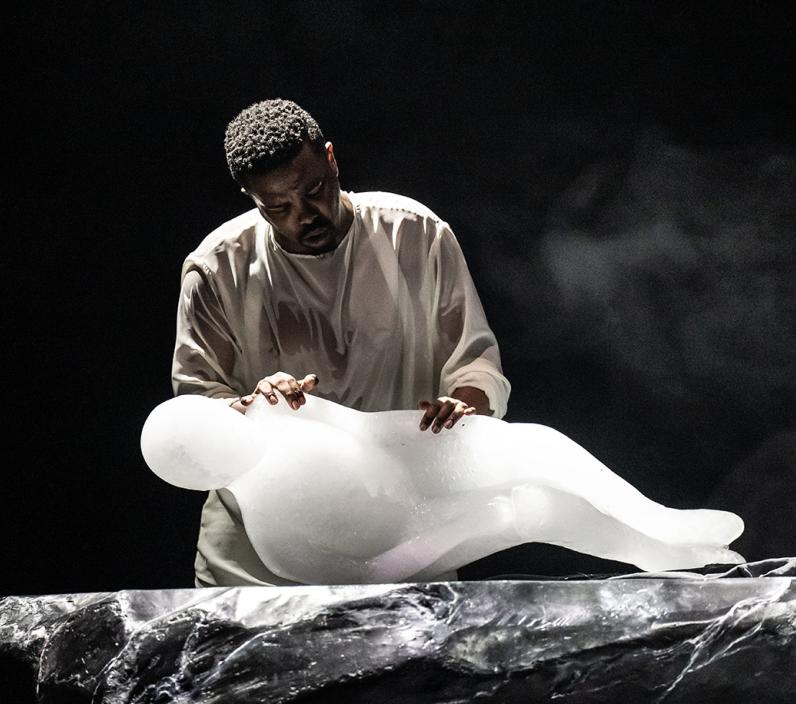

When he sings, the animals stop and listen; Orpheus can literally melt stone. To find Eurydice, who disappears on their wedding day, this master of harmony must charm the underworld with his musical talent. Orpheus’s appeals convince Pluto to free Eurydice, under certain conditions. But when this gifted and infallible hero fails, he must live on with the consequences.

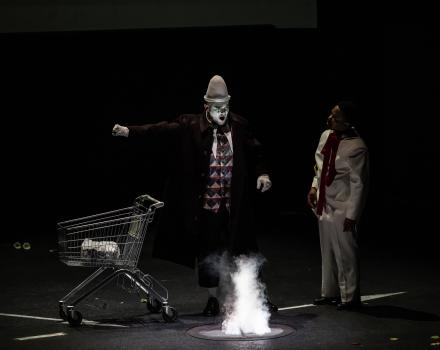

Live on the opening night, Staatsoper Hannover presents Orfeo, the cruel story of a great love. Orpheus cannot get over the death of his beloved; he longs and yearns for her and loses himself in loops of loss. Following the success of Like Flesh in Lille, director Silvia Costa and her team tackle Monteverdi’s masterpiece. Often using otherworldly images in her work, Costa imagines an enigmatic universe of dreams and hallucinations, of colours and symbols where Orpheus is bereft and disorientated. The production is conducted by baroque specialist David Bates, who brought Trionfo splendidly to life in Hannover and on OperaVision.

CAST

|

Orfeo

|

Luvuyo Mbundu

|

|---|---|

|

Messenger

|

Nina van Essen

|

|

La Musica

|

Nikki Treurniet

|

|

Hope (La Speranza)

|

Nils Wanderer

|

|

Euridice

|

Nikki Treurniet

|

|

Caronte

|

Markus Suihkonen

|

|

Plutone

|

Richard Walshe

|

|

Proserpina

|

Nina van Essen

|

|

Nymph

|

Petra Radulovic

|

|

Pastore I

|

Philipp Kapeller

|

|

Pastore II

|

Pawel Brozek

|

|

Pastore III

|

Nils Wanderer

|

|

Apollo

|

Marco Lee

|

|

Chorus

|

Chor der Staatsoper Hannover

|

|

Orchestra

|

Niedersächsisches Staatsorchester Hannover

|

| ... | |

|

Music

|

Claudio Monteverdi

|

|---|---|

|

Text

|

Alessandro Striggio

|

|

Conductor

|

David Bates

|

|

Director

|

Silvia Costa

|

|

Sets

|

Silvia Costa

Michele Taborelli

|

|

Costumes

|

Laura Dondoli

|

|

Lighting

|

Bernd Purkrabek

|

|

Dramaturgy

|

Martin Mutschler

|

|

Chorus master

|

Lorenzo Da Rio

|

| ... | |

Videos

STORY

Prologue

Music commands silence while she tells the story of Orfeo, the son of Apollo, god of music.

Act I

Revellers celebrate the wedding day of Orfeo and Euridice.

Act II

Orfeo rejoices in his union with Euridice. A messenger arrives with the terrible news that Euridice has been bitten by a snake and has died. Orfeo despairs and then resolves that he will rescue Euridice from the underworld.

Act III

Hope accompanies Orfeo to the gateway of the underworld, which is guarded by Charon. At first, Orfeo’s music fails to charm Charon but eventually he is lulled to sleep and Orfeo is able to pass him by.

Act IV

Proserpina, queen of the underworld, is moved by Orfeo’s music and begs Pluto, king of the underworld, to release Euridice. Pluto agrees, on condition that Orfeo neither speaks to her nor turns around to look at her while leading her back. As they travel, Orfeo doubts that Euridice is really behind him and is unable to resist turning to look. Euridice is taken from him for the second time and Orfeo is forced to return to his own world.

Act V

Consumed by grief, Orfeo renounces all women. His father, Apollo, takes pity on him and offers him a life in the heavens, making music for immortality.

Insights

Claudio Monteverdi had already made a name for himself with his innovative music as Kapellmeister at the court of the Duke of Mantua when, in the early 1600s, he turned to the legend of Orpheus. In this composition, which was by no means the first musical exploration of the material, he succeeded in returning to its origins in antiquity, in keeping with the inclination of his era. For it was wrongly assumed at the time that all text had been sung on the stages of Greek antiquity. Before Monteverdi, there were mainly mixed forms in which stylised spoken text and song alternated, but he had in mind a new immediacy of emotional expression in song.

Orfeo is about the power of shaped sound, about how music moves the seemingly immovable, how Orpheus can even influence the direction in which the water flows through his singing. This is perhaps another reason why Monteverdi is so precise when it comes to the flow of speech and rhythmic notation in his music. This is where the work on the piece begins: with the question of what the main feeling is about each phrase, what Monteverdi may have had in mind. Considering this and the large arc of the phrase, there is a direct emotional impression in the line.

This music only comes alive through a close inspection of the material; one proceeds almost like an archaeologist. You dig for quite a while, but once you get to the core, you just have to let what you have found shine in its own glory. Therefore, every nuance in the musical syntax should be taken into account and the singers should also be encouraged to seek out this total precision.

Improvisation plays a role, but less than one might think. Ornaments such as the trillo (a rapid repetition of the same note, which can express excitement or longing depending on its intensity) or the messa di voce (the rise and fall of volume on a sustained note) are possible. But even these effects should serve the fundamental principle ‘prima le parole, poi la musica’, words first, music second.

The director and set designer Silvia Costa interprets the tragedy in her own way. In her eyes, the tragedy has already happened. What we as the audience experience is a main character caught between the desire to let go and the desire to come close to the beloved friend in reliving the past. We see Orpheus lost in an enigmatic round of dream worlds, wishful images and hallucinations. The feedback loops of memory glow seductively. But in this world, nothing is real except reliably recurring pain.

The audience is invited to scan the images with their own experiences to test their truthfulness. How real is the observation of what is happening? What images, what feelings are evoked when one sees the whimsical choreography of bodies? How concrete are these shadows that claim to be people? Are the chimaeras only from Orpheus’s imagination as he relives memories? Will he be delivered from his nightmares? And does he even want to wake up?

Adapted from programme texts by conductor David Bates and dramaturge Martin Mutschler.

Gallery