A contemporary operatic thriller that follows a young violinist's descent into obsession, a production which won the FEDORA - GENERALI Prize for Opera.

Cast

|

Martin

|

Aaron Monaghan

|

|---|---|

|

Hannah

|

Márie Flavin

|

|

Amy

|

Sharon Carty

|

|

Matthew

|

Benedict Nelson

|

|

Chorus

|

Wide Open Opera Chorus

|

|

Orchestra

|

Crash Ensemble

|

| ... | |

|

Music

|

Donnacha Dennehy

|

|---|---|

|

Conductor

|

Ryan McAdams

|

|

Director

|

Enda Walsh

|

|

Sets

|

Jamie Vartan

|

|

Lighting

|

Adam Silverman

|

|

Costumes

|

Joan O'Clery

|

|

Text

|

Enda Walsh

|

|

Chorus master

|

Killian Farrell

|

| ... | |

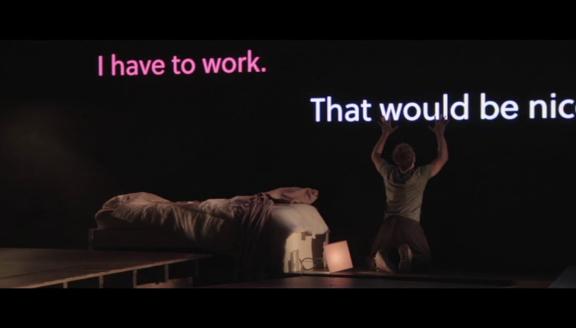

Video

The story

Martin is a second violinist in an ensemble, in love with the music of Carlo Gesualdo.

Martin’s life is falling apart. He drinks and plays endless video games. He doesn’t practice violin nearly enough. He does not answer his messages. Martin makes a dating profile under the pseudonym of Carlo. Martin writes and rewrites this profile: first as an enthusiastic violinist, then as the composer of an opera, and, finally, 'alone'. When he is at his most desperate, a voice reaches out to him from his computer screen.

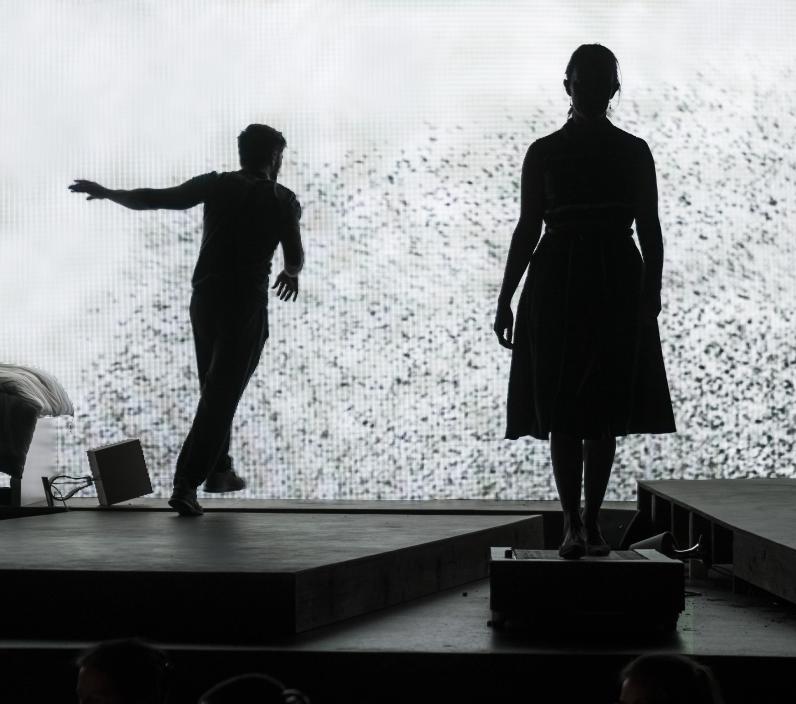

Matthew and Amy are a married couple. They are hosting a houseguest, Hannah. We see Martin swirling around this configuration. Amy is in love with Hannah and her marriage to Matthew is breaking down. Once Matthew discovers his wife’s affair, he murders the lovers, which echoes the composer Gesualdo’s notorious murder of his wife and her lover.

As the opera progresses it becomes increasingly apparent that Martin is viewing his own past. He arranges to meet the owner of the voice from his screen in a forest. Here is where things will end…

Insights

Irish mezzo-soprano Sharon Carty created the role of Amy in Dennehy’s opera. She spoke to OperaVision about the process in approaching the rehearsal and performance of a new role.

In the Second Violinist, how do you feel that your character speaks? What's her voice?

It’s actually a really interesting thing to think about! The issue of voice and perspective in the opera really preoccupied me as we were rehearsing it. When we got to the stage of having the full show up and running, it became clear that there’s no one absolute truth: there’s no one perspective that is definitive, in my opinion, in any case. Everything is kind of in Martin’s memory, but then you’re not sure whether that’s how it actually happened, or whether it’s filtered through his consciousness and his point of view. Then you also have lots of apparently “objective” outside information, like snippets of colleagues speaking about him, or friends leaving him unanswered voicemails. For me that all points to there not being one definitive perspective. And then because the actor Martin being silent, you have to ask yourself whether the whole projection of these three singing characters is true to life, or just through the lens of Martin’s perception. Do the words the singing characters sing come truly from them? Or is it what Martin perceives that they’d think? It leaves you a little bit unsure of whose version is the correct one. Which is a good thing I think, as it means the audience has to do a bit of work! There’s no such thing as the truth!

In terms of Amy’s voice, I think she has two modes of expression. One which takes up quite a lot of her stage time is the public persona, and centres around how she’s defined in relation to other people: her relationship with Matthew, the expectations of being a wife and being in a marriage, and her friendship with Hannah, which reminds her of a more hopeful, freer time. In order to escape her unhappiness with Matthew, she tries to jump into another relationship with someone else. For me she’s constantly defining herself in terms of her relationship to other people.

But the two solo arias tell a different story. Whereas Hannah’s aria and one of Matthew’s involve the characters in conversation (or even confrontation) with each other, Amy’s are much more introspective, and betray a deep disappointment in her marriage and in her husband, ultimately forcing her into the decision to leave him, with disastrous consequences. But she never says these things outwardly. The audience gets to listen in, of course, but she never actually confronts Matthew to tell him she’s leaving him for Hannah. The hope and private conquering of her feelings as depicted in her second aria is all the more poignant when we see the outcome of Matthew devastating actions later that night.

In the opera, much of the focus is on Martin and his obsession with Gesualdo. How do you think that obsession translates to his obsession with Amy?

There certainly are parallels between Martin and Gesualdo sprinkled throughout the opera. Gesualdo was recognized as an actual genius. His music is groundbreaking. Some parallels are clearly applicable and some a bit more forced by the character of Martin. Again, I think this is for the audience to decide, as well. As the opera unfolds, there are clear indications that the character, Martin, is suffering from major mental instability, he ultimately ends up murdering his wife and her lover, just as Gesualdo did. In his online dating profile he tries to frame himself as a misunderstood genius. Whereas in fact, you hear voicemails being unanswered, and overhear conversations about how he’s not playing well, not practicing, not being prepared for his rehearsals. You see him not really care for his violin properly, he doesn’t even treat the instrument with respect. None of that paints a picture of a musical genius. He’s unable to come to terms with his shortcomings. He has his unfulfilled expectations of life. There’s a bit of a disconnect. I’m not sure though he’s obsessed with his wife in the same way that he’s obsessed with Gesualdo, or with himself! He definitely shows narcissistic tendencies!

The score is influenced by part of Gesualdo’s heartbreaking motet Tristis anima mea. Donnacha [Dennehy] has woven these motifs throughout the fabric of the score, and the chorus sing an almost direct transcription of the second half of the motet at one point, fulfilling the role of a sort of Greek chorus, commenting from outside the frame of the action. Earlier in the piece we see them dancing and having fun at a more literal “party for the chorus” in someone’s flat. Gesualdo himself is influencing the unfolding of the musical and dramatic tapestry throughout the show. Amy’s second aria is accompanied very prominently (and beautifully) by viola da gamba, and the gamba is present in the orchestral texture the whole way through, which gives this otherworldly, and somehow very ancient, feel to something that’s brand new.

This is a very contemporary opera using various new devices. How do you approach your performance practice for this type of production? Is your approach much different from the preparation process for a more "traditional" opera?

It’s mostly similar to how I’d approach a more traditional role, in so far as the preparation always starts with the score, regardless of whether the music has been around for 400 years or two months! In this case the score was my bible for the two months we had to learn it, and throughout the production. I found myself needing to use the full score, because of Donnacha’s very specific soundworld, and so that before the orchestra arrived I would always have in mind which instrument in the orchestra was accompanying, or a duet partner, and so on. Sometimes if you’re rehearsing contemporary music for four weeks with the piano reduction, and the orchestra comes in with a new soundscape, it can be quite a shock. We did have the midi file for the score as well which was hugely helpful, as well as an excellent piano reduction and an excellent pianist. In terms of preparation, a huge difference is that usually with an opera that’s been around a while, you have other performers’ interpretations to refer to, and you have access to a palette of artistic choices already made by other people, and that doesn’t exist obviously for something that’s new, so you have to rely on yourself and in our case the composer and conductor. Having Donnacha [Dennehy] in the room was absolutely incredible and Ryan [McAdams] was just phenomenal in shaping the entire thing and supporting us through the whole process. We were really lucky he’s on board! You can change what didn’t work in the rehearsal room, and Donnacha was able to make revisions as we rehearsed. That’s obviously different than a more traditional role: you obviously can’t ask Mozart, hey, what did you mean here?

In terms of staging, in a more traditional opera, your attention is generally (but not always, I know!) guided around the stage and you’re shown by the director what’s important to see and when. But in this show, you’re not at all allowed to be lazy as an audience member. There’s no sitting back! One of the things I adore about Enda’s work is about the open-endedness of his narratives. He makes the audience work for it, and so many people who saw the piece came to me days and weeks later to say they were still decided how they wanted to interpret what they saw. In the theatre, there are lots of different things happening in a lot of different parts of the stage simultaneously. Someone could be singing in the corner and a fight could be going on the other side, or there’s something on the video screen, so two different people might take away two slightly different “versions” of the evening. As an audience member, you have to be very alert to take in the information that’s given. And as Ryan (conductor) in fact pointed out, the piece rewards multiple viewings.

What are your thoughts on the relationship between early music and contemporary music?

There’s a very strong relationship between early and new music. As it happens, at the moment, most of my performance career is divided between early and contemporary repertoires. I think both allow for a deeply personal artistic voice. There’s probably a little more background work to be done in both repertoires than with others, but this is ultimately so rewarding. In early music repertoire, with ornamentation in da Capos, for example, you can put your own stamp on the performance as an artist. There’s a similar individuality to getting to be the first person to sing a role. The really lovely thing about this particular opera: this is my second world premiere, but the first one that was written specifically with my voice in mind. Because you’re the first person to do it, there’s no YouTube playlist of great mezzo-sopranos doing this role. You, in conjunction with the composer and the conductor, and the orchestra and your singer colleagues, get to bring this piece of music to the world for the first time which is very exciting, and also deeply personal.