In times of social change in Poland, love and pride collide: Bronia loves Casimir, who pursues a newly-widowed Countess. After the disastrous rehearsal for the festivities, Casimir realises Bronia’s sincerity. The Countess, too late, seeks his affection, but he chooses Bronia, leaving the Countess humiliated as the household celebrates the young couple.

Moniuszko’s opera The Countess is many things: comic, patriotic, satirical and touching. The great Polish operatic composer of the 19th century uses humor and social critique - mocking the shallow imitation of foreign customs in Warsaw salons, while also contrasting them with sincere, patriotic, rural Polish values. This new production is the main event of the 2025 Moniuszko Festival in the Poznań theatre that bears the composer’s name. Poznań Opera has entrusted the staging to Karolina Sofulak, a director who boldly seeks the universal message in the works she stages. Adding a subtitle to the opera, The Dream of Independent Poland, Sofulak set out to offer a broader view of the opera than just as a satirical commentary on Polish society at the turn of the 18th and 19th centuries. Will we find answers to the question of what national identity is when we look at the world created by Moniuszko and librettist Włodzimierz Wolski? And what was (and is) the role of women in its creation? And so, OperaVision continues its journey of discovery of Moniuszko’s work live here on 12 October 2025.

CAST

|

The Countess

|

Aleksandra Orłowska

|

|---|---|

|

Casimir

|

Łukasz Załęski

|

|

Bronia

|

Magdalena Pluta

|

|

Dzidzi

|

Rafał Żurek

|

|

Valentine

|

Wojtek Gierlach

|

|

Horatio

|

Rafał Korpik

|

|

Miss Eva

|

Małgorzata Olejniczak-Worobiej

|

|

Orchestra

|

Poznań Opera Orchestra

|

|

Chorus

|

Poznań Opera Chorus

|

| ... | |

|

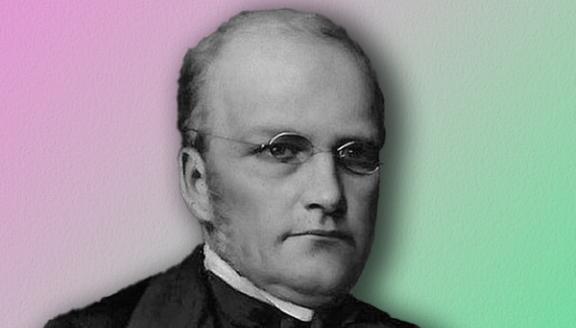

Music

|

Stanisław Moniuszko

|

|---|---|

|

Text

|

Włodzimierz Wolski

|

|

Director

|

Karolina Sofulak

|

|

Conductor

|

Katarzyna Tomala-Jedynak

|

|

Sets

|

Dorota Karolczak

|

|

Costumes

|

Ilona Binarsch

|

|

Lights

|

Giuseppe di Iorio

|

|

Choreography

|

Monika Myśliwiec

|

|

Video

|

Karolina Fender Noińska (Jajkofilm)

|

|

Chorus master

|

Mariusz Otto

|

| ... | |

VIDEOS

STORY

Act I

A 19th-century salon. A cheerful crowd awaits the Countess’s ball, where the famed Warsaw socialite, Madame de Vauban, is expected to appear. Bronia catches Dzidzi’s and Valentine’s eye.

Dzidzi encourages Valentine to court her. Valentine plays coy, but he’s not entirely unwilling. Dzidzi himself is unrequitedly in love with the Countess, who favours Casimir. Horatio shows up, mocking Valentine’s sentiments. He doesn’t know that it is his granddaughter who is the object of affection.

Meanwhile, Bronia is not impressed by the glitz and glamour of high society. She longs for the peace and quiet of the countryside. Bronia bumps into distressed Casimir, who’s suffering because of his love for the Countess. He fears his feelings are not being reciprocated. Hearing his concerns, the Countess advises him to believe and remain hopeful. Dzidzi appears, announcing the arrival of a ball gown. The Countess, stunning in her attire, arouses universal admiration. Rehearsals for the ball’s accompanying performance can begin.

Act II

The interwar period. The space is bathed in a dreamlike glow. The guests, led by Miss Eva, prepare for rehearsal – among them the Countess, who’s making ambitious plans. Casimir, half-asleep, watches a series of tableau vivants drift before his eyes – a dance of pearls, Neptune’s court, a military parade.

Valentine and Dzidzi actively participate in the festivities, but Bronia can’t find a place for herself. The arrival of Madame de Vauban is announced. What a thrill! Casimir clumsily offers his hand to the Countess, tearing her dress. The event causes a stir among the guests.

Act III

The turn of the 1990s. The Countess and Miss Eva lead the Ladies’ polonaise. At the same time, the gentlemen return, led by Valentine. Bronia yearns for Casimir. The Countess also hopes to meet him, regretting her violent outburst.

Dzidzi mocks her longings. Casimir returns. His heart leans more towards Bronia than the Countess. He makes his change of heart clear. Valentine decides to end the impasse between the lovers. He proposes to Bronia in Casimir’s name.

The Countess walks away, her hopes and dreams trampled. The guests raise a toast to the health of Bronia and Casimir.

INSIGHTS

Poland tries on a new dress

Director Karolina Sofulak in conversation with Agnieszka Drotkiewicz

Agnieszka Drotkiewicz: Based on the libretto, we could say that The Countess is a love triangle set in the time of Stanisław August Poniatowski (the last king of Poland, in the 18th century), couldn’t we?

Karolina Sofulak: Yes – moreover, it is often described as a satire on social divisions. Yet, in my view, it is a much more profound story, one that touches on independence – both national and personal. The title heroine is a countess, and the question of a woman’s independence, her development, and her agency is strongly emphasized.

In preparing The Countess, how conscious are you of earlier stagings which offered different interpretations?

The Countess is deeply rooted in the Polish geopolitical situation of the 19th century. This is already signaled in the overture: the first notes echo elements of Mazurek Dąbrowskiego (Dąbrowski’s Mazurka – the Polish national anthem) drowned in an old-Polish toast. This musical frame both opens and closes the opera. Poland and Polishness are the main themes of this opera. The rest reflects the composer’s observations of the tensions which existed – and still exist – in Poland to this day. When we look at the characters, they resemble archetypes we recognise from our own lives. The title heroine is a woman for a reason. Nonetheless, both critics and some stage interpreters have tried to ‘amend’ the composer and the librettist, referring to the opera as Pan Kazimierz (Mr Casimir) – a paraphrase of Pan Tadeusz (Sir Thaddeus). Kazimierz is the one for whom the Countess’s heart beats, while Bronka is her younger and humbler rival. But that’s where the resemblance to Telimena and Zosia from Mickiewicz’s epic poem ends – in the short story on which Włodzimierz Wolski based his libretto, the Countess is merely an eighteen-year-old widow. The staging tradition doesn’t seem to interpret the work from the perspective of the title character. The role of women in society – their available paths of development – is emphasized in this story. Dress and attire are vital elements of the narrative, and on a much deeper level than the opposition of ‘tails and kontusz’; the former symbolizes yielding to foreign influences and the latter (an outer garment worn by Polish nobility) an attachment to national values.

You are known as a director who listens closely to the music and honors the composer’s intentions. How did your previous work on other operas shape your approach to The Countess?

I see an especially interesting parallel between Verdi and Moniuszko. It lies in the way these two composers are perceived: as monumental figures in the newly defined countries of the 19th century. Too often, however, this view is taken uncritically – without peeking deeper, beneath the surface of their works. Yet, both Verdi and Moniuszko were acute observers of their times and unusually progressive artists, vividly inspired by social changes and the position of women. That’s why their stories are so easily told today. I can feel the pulse of contemporary themes in their music.

One of the key moments in The Countess is the rehearsals for the ball, which shows tableaux vivants of mythological scenes. Quoting mythology can be seen as a way of suggesting that erudition and culture knows no borders, and the category of ‘Polishness’ is not opposed to ‘Europeness’ but is in fact one of its integral components. Is this how you see it?

Absolutely – and that’s why the opposition between ‘tails and kontusz’ holds little interest for me. Let me return to the music, because it is made abundantly clear in the score: Moniuszko skillfully navigates the traditions of European opera with which he was so familiar. We can hear his admiration for Auber, echoes of Donizetti and Rossini, references to Mozart, and even a brief journey back to the Baroque and its arias, when the composer plays with the da capo form. Moniuszko mixes all these allusions with an original Slavic idiom that refreshes opera’s status quo. Also, Moniuszko composed The Countess just after returning from his first trip to Paris, where he was influenced by the latest ideas of socially engaged French theatre. Neither erudition nor music knows borders. True education lies in engaging with works of art from many cultural traditions. It’s crucial to me, as I also hold a degree in comparative literature and view European culture as a multi-dimensional network of interconnections – one that stretches far beyond the rigid borders drawn by maps and by history.

How did that inspire you to tell this story?

We’re placing it on a sort of ‘merry-go-round of history’. Our three acts turn into three dreamlike visions of three Republics of Poland: the first, which ended in partitions – the second, the interwar Republic – and the third act, sets us around 1989 – though it could be the present day. This gives us food for thought: we’re coming back to Poland’s last great upheaval. The story of our characters unfolds across centuries, with incarnations of the same personas appearing on stage. In our interpretation, Poland continuously tries on new dresses – just like the Countess.

Exactly! What kind of metaphor is the Countess’ dress in your reading?

Let’s start with the libretto itself. The opera was created in the second half of the 19th century, setting the plot in the 18th century is one of these ‘frocks’ which aimed at outwitting censorship. And when it comes down to the Countess’ dress, in my personal view, it is the key theme of the story we are telling: it is a story about dress-changing, where the concept of the robe is understood very broadly – as a public role, as social reputation and as a measure of respect. In the second act, a highly important moment for us is the aria which begins with the words: ‘O dress! You have arrayed me.’ For our protagonist the dress isn’t just the means of highlighting her beauty, attractiveness as a woman. The dress is inseparably connected with the Countess’ public role – she hosts a salon, a cultural gathering that, during the times of both Stanisław August Poniatowski and later Moniuszko, functioned as closely as possible to a contemporary public role of an arts manager. A salon served not only entertainment purposes but also culture-building and diplomatic roles. The dress of the host has then a representative role, the Countess sees in it the way she is seen by the others – her identity, her dignity. Not coincidentally, it’s the dress of Diana, goddess of the Moon, of women’s spheres and also of hunting. You mentioned the living pictures depicting mythological scenes. That’s essential, as Greek mythology for the people of the 19th century and their ancestors functioned like a modern base of memes in pop culture – everyone knew more or less what it was all about. From the first bars, we know we are going to watch Hercules and Omphale, so, according to this mythological keyword, the genders are to switch their roles – the theme being a gender à rebours. By putting on Diana’s dress, the Countess impersonates a woman who hunts for a man, while simultaneously executing her culture-building potential.

Gallery