Golden Crown

Set in the Ukraine’s Carpathian mountains in 13th century, Golden Crown is an epic love story of the love, loss, betrayal, class, stolen land and national pride - all of which conspire against the star-crossed villager Maxim Berkut and his beloved Myroslava, the daughter of a local nobleman.

Ukrainian composer Borys Lyatoshynsky wrote Golden Crown in 1929, when the policy of ‘korenizatsiya’ (going back to the roots) was allowed in the country. At this time, several operas were commissioned from Ukrainian composers and librettists based on Ukrainian history. In support of 21st century Ukraine, OperaVision presents an unprecedented international online co-production of this opera never before performed outside Ukraine. Released on 25 October 2022 to mark World Opera Day, this production is the fruit of a collaboration between seven cities: Helsinki, Lviv, London, Rome, San Francisco, Warsaw and Washington DC. Young artists from Finnish National Opera, Lviv National Opera, Royal College of Music, Teatro dell’Opera di Roma, San Francisco Opera, and Polish National Opera each perform a scene from Golden Crown. The production is narrated by Ukrainian artists attending the Shenandoah University, near Washington DC, where Ella Marchment, who initiated and directs this production, is Director of Opera.

Fundraising campaign

Today, the opera community stands shoulder to shoulder with Ukraine and OperaVision is happy find new admirers for Ukrainian culture across the world. While, thanks to the support of the European Commission, we continue to offer OperaVision as a free service, we now encourage you to give generously to our fundraising campaign to support the next generation of opera singers and managers from Ukraine. Give here. Thank you.

Cast

|

▪ Finnish National Opera

|

|

|---|---|

|

Myroslava

|

Minna-Leena Lahti

|

|

Maxim Berkut

|

Tuomas Miettola

|

|

Tugar Vovk

|

Arttu Kataja

|

|

Piano

|

Hans-Otto Ehrström

|

|

|

|

|

▪ Lviv National Opera

|

|

|

Zakhar Berkut

|

Taras Berezhanskyi

|

|

Chorus

|

Male Chorus of Lviv National Opera

|

|

Piano

|

Marianna Rusak

|

|

|

|

|

▪ Polish National Opera

|

|

|

Myroslava

|

Justyna Khil

|

|

Maxim Berkut

|

Adrian Domarecki

|

|

Tugar Vovk

|

Adrian Janus

|

|

Piano

|

Klara Janus

|

|

|

|

|

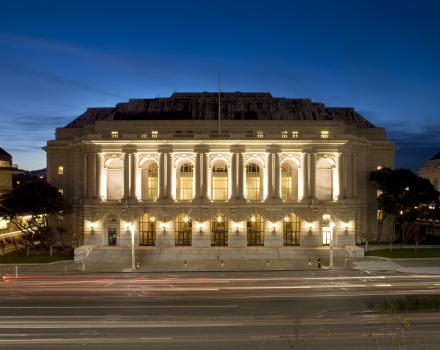

San Francisco Opera

|

|

|

Zakhar Berkut

|

Stefan Egerstrom

|

|

Piano

|

Kseniia Polstiankina Barrad

|

|

|

|

|

▪ Royal College of Music

|

|

|

Maxim Berkut

|

Michael Gibson

|

|

Tugar Vovk

|

Jamie Woollard

|

|

Piano

|

Paul McKenzie

|

|

|

|

|

▪ Teatro dell'Opera di Roma

|

|

|

Myroslava

|

Agnieszka Jadwiga Grochala

|

|

Maxim Berkut

|

Rodrigo Ortiz

|

|

Zakhar Berkut

|

Arturo Espinosa

|

|

Piano

|

Elena Gurina

|

|

|

|

|

▪ Shenandoah University

|

|

|

Presenter

|

Ella Marchment

|

|

Narrators

|

Illia Kozlov

Marina Duane

Iryna Horodnycha

|

| ... | |

|

Music

|

Borys Lyatoshynsky

|

|---|---|

|

Text

|

Yakiv Mamontiv

|

|

Ukrainian adviser

|

Galyna Grygorenko

|

|

Musical adviser

|

Caleb Glickman

|

| ... | |

Video

Story

Act I

In the mountains of Zelemenya in 1241, grandmother Mavra gathers herbs from the forest while carefree youngsters play and dance. Horns ring out and a hunting expedition for bears led by the local boyar Turgar Vovk arrives with his beautiful daughter Myroslava. They seek a brave young villager to hunt with them and the local boys quickly nominate Maxim. Whilst Myroslava is happy about this choice, Tugar insults Maxim by claiming that Maxim’s father and chief of the villagers, Zakhar Berkut, used to incite the peasants against the boyars.

Maxim accuses Tugar of seizing the land illegally, whereas Tugar claims that he bought it off a Prince. Maxim is so confident in his claim that he offers to go to public court, but he is attracted by Myroslava, so backs down in order to join the hunt. Myroslava accidentally discovers the bear’s den. She blows her horn immediately to call for help and Maxim is the first one to answer. After a fierce fight, he kills the bear and declares his love to Myroslava. Even Myroslava's father is forced to express his gratitude to the hero. Maxim asks for Myroslava's hand, but Tugar Vovk refuses because Maxim is not a boyar.

The village leader gathers his people around the symbols of his village (a red banner and a golden crown) and informs them that the Mongol-Tatars have captured Kyiv and that they should prepare themselves for battle. He also predicts that the boyars (who should protect them) will in fact betray them if they sense it will leave them better off. In an attempt to preempt Tugar and the boyars, Berkut initiates a public trial about the initial land ownership. It concludes that Tugar is lying about owning the land, and as a punishment will be expelled from the area and his house destroyed. Maxim is entrusted to carry out the sentence. He is grief stricken at the task, because it involves destroying the house of the woman he loves.

Act II

A few days later, Tugar Vovk and Myroslava have fled to the Tatar camp, as Berkut predicted. Tugar is ready to enlist in Tartar service, but Myroslava, like the villagers, is appalled by this betrayal. She charms the Tatar chief into allowing her free passage through the guards towards escape.

Maxim leads the peasants to the manor of Tugar Vovk to carry out his instructions. As he sets fire to the manor, a Mongol detachment led by Tugar suddenly appears and a battle breaks out. The Tatars kill nearly all their opponents and capture Maxim.

In the final scene of the act, it is nightfall in the Tatar’s camp where Tugar Vovk and Myroslava have fled, and Maxim is imprisoned. Myroslava has a plan to free Maxim, but Maxim is reluctant to sacrifice anything in return for his release.

Act III

A new day dawns in the Dazhbog cave in the rocks of Zelemen. Zakhar Berkut reflects on the natural beauty of the area before it became populated and transformed into a land of war. To rid the area of the Mongols, he has the idea to block the dam in the valley and flood them out.

Tugar Vovk appears with Myroslava and disrupts Zakhar Berkut’s thoughts. Tugar has come to present an offer from the Tatars. If the villagers open the way for their troops to pass through, in return the Tatar’s will release Maxim and retreat to Hungary. Zakhar Berkut thinks that Tugar is lying about the whereabouts of his son. He declines the offer and expels Tugar. Myroslava stays behind and begs Zakhar to listen and to take her as his daughter. As the sun rises the next day, Zakhar finally hugs her. Myroslava is accepted into the village family and stays behind with them.

Meanwhile, in the Tatar’s camp Maxim pretends to be ready to take the Mongols out of the valley by a secret route. Maxim wins Tugar round with his proposal. Maxim is now free of his shackles and Zakhar Berkut’s Tukholts open the dam and the camp begins to flood. In the midst of the chaos Maxim escapes. The camp leader, believing Tugar to have committed treason, kills him on the spot.

Maxim returns a hero to the Tukholts camp, but he has been seriously wounded and dies in the arms of both his love and his father. The peasants mourn the dead and the opera ends with the red banner and golden crown of the village being unfurled. Victory is won, but at the expense of all the people closest to Myroslava.

Insights

Borys Lyatoshynsky’s first opera Golden Crown (1929) is important in the history of Ukrainian music. It marks the most original period in the composer's work in the 1920s and is distinguished by its innovation, philosophical depth, original orchestration and masterful use of ancient folk sources. The premiere of the opera took place in 1930 in three opera theatres and under three different titles: Odessa as Zakhar Berkut, Kyiv as Berkuty and Kharkiv as Golden Crown.

The Opera in Odessa was the first to present the opera on 26 March 1930, and the premieres took place in Kharkiv and Kyiv in October 1930. The best Ukrainian singers performed at these performances, alongside the leading conductors, ballet masters and scenographers. For the planned performance in Moscow in June 1930, the libretto was translated into Russian but underwent forced ideological changes. In the end, the performance never took place in Moscow.

In 1936, accusations of formalism were levelled at Lyatoshinsky's Golden Crown. According to one critic, ‘bare formalism prevails in the opera under the harmful influence of modernism, and the folk song is horribly distorted for purely formalistic reasons.’ For many years, the opera was removed from the repertoire of opera houses. In 1970, the second edition of the opera was performed on the stage of the Lviv Theatre of Opera and Ballet named after Ivan Franko. Golden Crown was staged for the third time in 1989 at the Kyiv National Opera House.

The concept of formalism in art was a characteristic feature of the avant-garde at the beginning of the 20th century, from the second half of the 1920s onwards. Any experiment with form and content of artistic works in the USSR, however, was dogmatically interpreted as a manifestation of formalism, persecuted, and evaluated from a political rather than aesthetic point of view. Borys Lyatoshinsky was accused of formalism more than once during his creative life.

After the attack on Golden Crown and its removal from the repertoire, Lyatoshinsky’s Second Symphony, after numerous postponements, was severely criticised at the general rehearsal in Moscow and was not allowed to be performed in February 1937. In 1948, the Ukrainian Central Committee of the Communist Party of Ukraine (ЦК ВКП (б)) issued its resolution, where Lyatoshynsky was called the main formalist in Ukrainian musical art. This, as well as the devastating criticism in 1951 of his Third Symphony and forced changes in the music, was a terrible blow to the composer.

Borys Lyatoshynsky wrote to Lev Chetvertakov from Kyiv on 4 June 1948:

‘First of all, I must inform you that on 23 May the Central Committee of the Communist Party of Ukraine published its resolution on the state of music in Ukraine, and I appear in this document as the main Ukrainian formalist, who has several followers, also named in the resolution. […] As for me personally, I am, of course, more than amazed at such qualifications of me. Without denying in the least that before the war I was complex (but, of course, many times simpler than the same Shostakovich), during the war I greatly simplified my language. At times it seemed to me that I had simplified myself to the point of obscenity […] In all my compositions I based myself on Ukrainian folk intonations. Everything that I wrote during the period of the war can in no way be called formalistic. This is my deep conviction. All this, however, is not taken into account in the decision. What is not taken into account is that it was through the folklorism, which is mentioned in the February resolution of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of Ukraine, that I became much clearer and more understandable. […]

It is clear that when this Ukrainian decree came out, I had to say at meetings and at the Union of Composers and at the Conservatory that I agreed with everything. I couldn't argue with the Central Committee! As a result of the decision, I completely disappeared from all Ukrainian concert and radio programme, and I felt that I was a formalist judging by my empty pockets too.

That's it.’

Gallery