A Verdi opera that is rarely performed - lucky you, the tenor Michael Fabiano performs the title-role, Corrado!

Cast

|

Corrado

|

Michael Fabiano

|

|---|---|

|

Medora

|

Kristina Mkhitaryan

|

|

Gulnara

|

Oksana Dyka

|

|

Seid

|

Vito Priante

|

|

Giovanni

|

Evgeny Stavinsky

|

|

Orchestra

|

Orquestra de la Comunitat Valenciana

|

| ... | |

|

Music

|

Giuseppe Verdi

|

|---|---|

|

Conductor

|

Fabio Biondi

|

|

Director

|

Nicola Raab

|

|

Sets

|

George Souglides

|

|

Costumes

|

George Souglides

|

|

Fight Choreography and Video

|

Ran Arthur Braun

|

| ... | |

Video

The story

Act I

The Greek island of the corsairs. Aboard his ship, the chief corsair Corrado, who is in exile, laments his existence as a pirate. He shows his determination to fight against the Turkish Pasha, Seid, and is applauded by his men. Meanwhile, alone in her room, his beloved Medora is fearful for Corrado’s fate and she puts her thoughts into words in a mournful song. The corsair arrives and tells her of his battle plans. Despite her fears and after pleading with him not to go, Corrado leaves her to face the enemy.

Act II

The Turkish city of Corone. In Seid’s harem the odalisques pamper Gulnara, the Pasha’s favourite. But she longs for freedom and to return to her homeland. A messenger brings her an invitation for the celebration that Seid is preparing for after the anticipated defeat of the corsairs. Before the banquet, Seid asks Allah for his protection. Once the celebration is underway, a dervish asks Seid for protection after having escaped from the corsairs. Seid accepts and then receives the news that the Turkish fleet is in flames. The dervish reveals his identity: it is Corrado, who attacks with his men. When the battle appears to have been won, the news that the harem is in flames makes Corrado stop fighting and rescue Gulnara along with the other women. Seid takes advantage of this to counterattack. Finally, Corrado is arrested. Impressed by his brave gesture towards her, Gulnara puts in a good word for the corsair, but Seid condemns him to death.

Act III

Seid’s victory is marred by the suspicion that Gulnara is in love with Corrado. The defiant attitude of the slave girl fills the Turk with rage.

Gulnara visits Corrado in his cell and gives him a dagger: she has bribed the guards so that he can escape and kill Seid with the weapon. When Corrado refuses to kill the Turk in such a despicable way, Gulnara decides she will do it herself. A storm blows up after she has left. When she returns, she tells Corrado that Seid is dead and offers to escape with him. Corrado accepts and they run off together towards the island of the corsairs.

The Greek island of the corsairs. Medora, in despair from having received no news of Corrado, has taken poison to end her own life. As she lies dying, the corsairs’ ship arrives and Corrado and Gulnara run to the unfortunate Medora’s side, who dies in the arms of her beloved. In despair, Corrado throws himself off a cliff despite the efforts of his men to stop him from doing so, and Gulnara faints.

Insights

Within the poet's mind

In 1814 'The Corsair' by Lord Byron was published and sold 10.000 copies on the 1st day alone, an unprecedented success for a poem. It is loosely connected to Byron's own journeys in Greece, but draws heavily on the authors inner personal world and also some of his political views. Verdi was immediately attracted by its romantic emotional power and asked Francesco Maria Piave to turn it into a libretto.

Corrado, the corsair, is fighting all mankind, to free the oppressed, but is suffering from the task he set himself as nevertheless it means war, death and destruction, also to the ones close to himself.

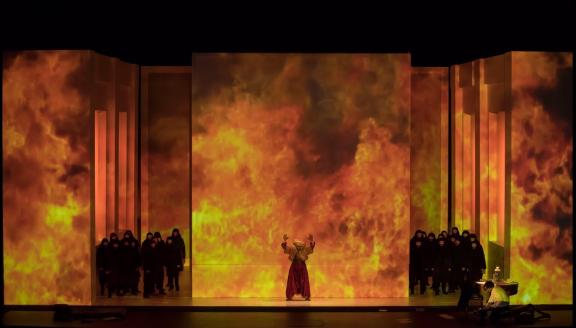

The resulting opera is extremely condensed and concise, less than 2 hours of music, and it feels like witnessing the events - despite changes of location from the Corsair's island to a Greek city under Turkish rule - in real time. The connection between main character and creator of the story seems palpable, and has led us to our decision, to internalise most of the plot. All outer events of action have become either memory or imagination, the poet therefore either reminiscing over his already finished scriptures or actively creating events and characters in his head and bringing them to paper. Finally, he enters his own story and looses himself in it. In the end we could say that we have witnessed the last 2 hours - the actual duration of the opera - of the life of the poet. We see and understand the destructive beauty of the process of creation, the dangers of entering into the world of one’s own mind, refusing to ever leave it again.

Nicola Raab, Stage Director

Gallery