In the grips of the Hundred Years War against England, the French find themselves in a difficult situation: Paris has fallen, Orléans is besieged, and their king, Charles VII, appears more interested in his affairs of the heart than those of the state. In this hopeless situation, the farmer's daughter Joan announces that God has commissioned her to liberate Orléans. The ‘Maid of Orléans’ may be victorious in battle but loses her heart in passion to a Burgundian knight, Lionel. The flames consume a woman torn between love and her divine mission.

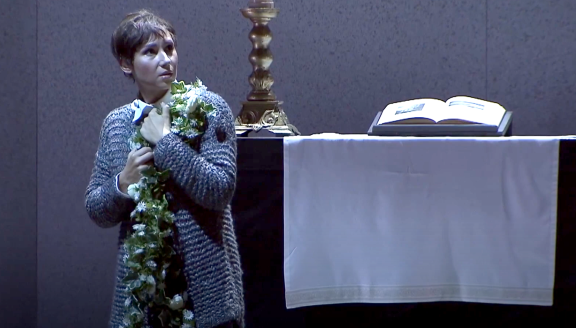

Inspired by Schiller’s tragedy, Tchaikovsky wrote The Maid of Orleans about the famous French heroine between 1878 and 1879. While Schiller sees her as an innocent, momentarily tempted by love for Lionel, Tchaikovsky permits Joan to indulge fully in her love and then die in religious ecstasy. Here is a historical heroine with something of the Tatyana from Eugene Onegin about her. Tchaikovsky’s score is filled with the same passion, with orchestral tumult, grand choruses, and beautiful arias, many reserved for Joan herself. Deutsche Oper am Rhein’s 2023 production has been ecstatically received by audiences and critics alike for Elisabeth Stöppler’s powerful staging (of an opera with quite some dramatic challenges) and for the outstanding performance of Maria Kataeva as the heroine leading a top-class ensemble.

Cast

|

Joan of Arc

|

Maria Kataeva

|

|---|---|

|

Thibaut d'Arc

|

Sami Luttinen

|

|

Raymond

|

Aleksandr Nesterenko

|

|

Charles VII.

|

Sergej Khomov

|

|

Agnes Sorel

|

Luiza Fatyol

|

|

The Archbishop

|

Thorsten Grümbel

|

|

Dunois

|

Evez Abdulla

|

|

Lionel

|

Richard Šveda

|

|

Bertrand

|

Beniamin Pop

|

|

Confessor

|

Johannes Preißinger

|

|

Lauret / a soldier

|

Žilvinas Miškinis

|

|

Angel

|

Mara Guseynova

|

|

Orchestra

|

Düsseldorfer Symphoniker

|

|

Chorus

|

Chor der Deutschen Oper am Rhein

|

| ... | |

|

Music

|

Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky

|

|---|---|

|

Text

|

Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky

|

|

Conductor

|

Vitali Alekseenok

|

|

Director

|

Elisabeth Stöppler

|

|

Sets

|

Annika Haller

|

|

Costumes

|

Su Sigmund

|

|

Lighting

|

Volker Weinhart

|

|

Chorus master

|

Gerhard Michalski

|

|

Dramaturgy

|

Anna Melcher

|

| ... | |

Videos

Story

ACT I

In her local church, Joan prays for consolation and peace. She tries, in vain, to hold on to the angelic visions which appear to her. Her distress is met with incomprehension and ridicule from the other women. Her father, Thibaut, vexed at his daughter’s reticence and otherness, accuses her of being possessed by the devil. It is only her betrothed, Raymond, who defends her. The war gripping the country is fast approaching, and in the neighbouring village houses are burned, fields ravaged and settlements devastated. Bertrand, a peasant, tells the gathered crowd about the horrific conditions on the front line in Orléans and of the deadly siege by enemy troops. Contrary to all predictions, Joan declares her belief in the King’s victory over his opponents, of the end to the enemy threat and the liberation of Orléans. Suddenly, soldier Lauret announces that the enemy’s leader has fallen in battle. This news makes the people believe that a miracle has happened and join Joan in passionate prayers. Joan feels compelled by her faith and inner conviction that she must abandon her old life and lead the fight. Another angel appears to her and prepares her for battle.

ACT II

King Charles is distracted from the troubles by his love for Agnes. Dunois, the commander of the royal army, tries in vain to restrain the King’s ardours and to remind him of his responsibilities as a ruler in a time of war. When the soldier Lauret dies at his feet from his war wounds, the King recoils and just wants to flee. Dunois resigns and Agnes starts to console Charles. The Cardinal appears and tells of a miracle – a mysterious young women has forced the enemy troops to flee. There are shouts of joy at this news and at the arrival of this ‘virgin’ of salvation. Joan appears. She reveals to King Charles her knowledge of his most secret prayers and he is enraptured by her. Joan describes her visions, which foretell of Charles’ victory and his coronation celebrations. Charles appoints Joan as the commander of his royal troops, to the cheers of the crowd.

ACT III

Lionel, an enemy soldier, takes refuge on the edge of the battlefield. Joan discovers and confronts him, challenging him to a life-or-death duel. Despite her superiority in the fight, she finds that she is unable to kill him. Confused, Joan struggles with her growing warmth towards Lionel, while he increasingly gives in to his growing affection for her. Dunois returns from the front with news of further victory. Out of his love for Joan, Lionel commits himself in service to Dunois to fight on the side of King Charles. Accompanied by Agnes and the Cardinal, Charles makes a triumphal entrance to celebrate the victory and to commemorate the dead heroes. In his speech of thanks, the King demands that Joan must offer proof of her holiness. Her father, Thibaut, publicly accuses his daughter of being possessed by the devil and calls on her to defend herself. Joan stays silent.

ACT IV

Despite the intense remorse and pain she feels about betraying her holy vision and her ideals, Joan admits her love for Lionel. When they meet again, they declare a bond of love and dream of a future together. But their bliss is only momentary… Lionel is killed. Joan is consumed by flames.

INSIGHTS

Joan, an Anti-Heroine in Times of War

Director Elisabeth Stöppler talks to dramaturg Anna Melcher.

Anna Melcher: Joan of Arc - no other historical female figure has been used so much as a symbolic figure for so many different political causes; no other has inspired so many artists. What fascinates you about Joan?

Elisabeth Stöppler: The fascinating thing about Joan is that she shines in so many different, even contradictory, directions and yet is also able to keep her own secrets. The historical figure of Joan of Arc still does not seem real; the irrationality of her actions has led to extreme transformations of her as an individual throughout history up until today, which, on the one hand makes her suitable as an idol of French right-wing populism and, at the same time, inspires the LGBTQIA+ community. This is a woman who - although being only slightly older than a child - gains an audience with the king; persuades him, without clear proof of her visions, to place her at the head of his armed forces; and who then, despite multiple victories on the battlefield, falls into political disfavour; is arrested; refuses to speak up to defend herself; is condemned and burned; and is posthumously canonised because of public pressure. This story is still sinister and yet fascinating.

It is a heavenly angel who tells Joan that it is her mission to go to war to free Orleans from the enemy and of the enthronement of the Dauphin Charles; and divine voices also prophetise her victory. What role does faith play in the narrative?

Joan's faith and her relationship with God was ultimately perceived as blasphemous by the Church of her time, which condemned her for not being able to control the visions and voices. I would describe Joan's expressions of belief as a strong, tangible gift to provoke transcendence, from which the radical power of persuasion arises, as well as the extreme ability to lead others and to inspire believe. That Joan believed in the miracle of the liberation of France is one thing - but that people believed and followed her, that her strong religious faith was able to create this concrete effect and ultimately influence masses of people, is the other thing; this seems to me to be the essential aspect.

Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky’s libretto and music expresses a lot about ‘glory’ and ‘victory’. The main character's words are bursting with battle cries, with which the virgin mobilises an entire nation. How does this rhetoric affect you and how did you try to contextualise it in your staging?

When I first read the libretto and the text of the play by Friedrich Schiller, I found the language to be quite repulsive. It is precisely this bellicose language that turns Joan into an extremely belligerent figure, and, at first, she seems anything but winning, but instead monstrous and unapproachable. Of course, this impression is softened by the beauty of Tchaikovsky's music. However, it intensifies the drive and the uncompromising nature of the statements because all the characters sound so infinitely passionate and, moreover, the entire choral masses join in with this powerful kind of speech. At the beginning, Joan preaches against the insecurity and suppression of the people and thus rises to become the heroine of a whole movement. It is important to show this tool, which the king also uses and later understands how to use it successfully - namely, that in an atmosphere of fear, the power of euphoria can be suddenly mobilised, and it develops a force that even Joan, in the end, can no longer control.

Can a ‘Joan of Arc’ still be a heroine today?

We no longer need heroism today, but clearly, we do need appropriate and distinct decision-making to bring about more solidarity and humanity, and also to clearly reject all inhuman political theories and concepts. Nowadays, a ‘Joan’ can only be an icon if she is pro-life and love, and against violence, destructiveness and viciousness. For me, however, Joan remains more of an anti-heroine, who always acts in a contradictory and stubborn way, and thus is even more unfit to be a heroine.

The many changing locations, ranging from a rural idyll to a massive cathedral, are condensed into only one space in your production. Why?

Our story takes place in a church, such as the ones that existed, and still exist, throughout Europe. On the one hand, such a place serves everywhere, and it still does today, as a public space where communities come together; at its best it prompts people to review their values and beliefs, and to rediscover them. On the other hand, we have chosen this sacred space of unity to give all of the characters - from the village girl to the cardinal - the possibility of experiencing this space as a place of transcendence, to experience something extraordinary, even irrational and unexplained. Our church is always a meeting space; later a shelter; and at one point the only possible living space left - until war takes it, too.

To what extent has the current war in Ukraine influenced your view of the material and the narrative?

The European war in Ukraine, which has affected all of us since last February, is the focus for the entire dramaturgy of this production. We could not and did not want to ignore the current situation, and we did it without any symbolism and just told the story as if it is a realistic, intense situation. The fact that is sung in the Russian language intensifies the connection between the staging and the reality, and it makes the crisis even more painful - because no one wins, if you attack one day you will be attacked the next day.

In the middle of the opera, a character suddenly appears who will change everything, a gamechanger who was not an historical figure: Lionel, who is a Burgundian and so an enemy fighter. What does the clash with this warrior trigger in Joan?

We show Lionel as a highly explosive, war-weary, even life-weary, fighter who can no longer make sense of war. That he brings this turn of events to Joan in the story is irrational and subjective - I think that he is just as strong and merciless as she is, that both mirror each other in their exhaustion, they find themselves reflected in each other and therefore develop this instant attraction and love. Lionel is responsible for Joan’s sudden feelings of empathy, shedding her guise as the war heroine, and emancipating herself into a compassionate woman who recognises and realises her responsibility for others. In this respect, the figure of the intransigent virgin achieves a new complexity through Lionel, and finally, in Tchaikovsky’s work, loses the static-heroic and symbolic persona, which, in Schiller's work, especially at the end, can make it so incomprehensible and alienating for us today.

The historical Joan of Arc was finally handed over by the court of the Inquisition to ‘the secular arm’ for sentence and execution. In Tchaikovsky's opera, the trial and condemnation are entirely absent; instead, the composer places the tragic love story between Joan and Lionel, who is killed just before Joan is executed, at the centre of his finale. Unlike Schiller, Tchaikovsky's Joan does not die on the battlefield but is burned, as the historical Joan of Arc was. Why did Tchaikovsky choose this ending? What does it mean for the figure of Joan?

Tchaikovsky, who as a young man had already written poems about Joan of Arc, identified himself very strongly with Joan. For him, her love weighed more than the ideal of having a faith in God, which is ultimately based on an inhuman commandment of chastity, so extreme that Joan's virginity is a precondition of her credibility. When, in the finale, the composer has his Joan take her choice of self-sacrifice, he, who throughout his own life felt himself to be an outsider and was generally ridiculed and pilloried because of his homosexuality, also stages his own pain and sacrifice. He sets it up for Joan to burn at the end because it atones for her forbidden love for Lionel, which has led her astray from her true path. For me, this surrendering and sacrifice develops into a more desperate struggle and remains a dilemma. So, finally, Joan stands not before a court, but before her own conscience. She does not merely sacrifice herself but dies in the chaos of a war which she herself has helped to ignite and is partly responsible for. This makes her an unredeemed and tragic figure with whom we can sympathise and for whom we can mourn.

Gallery