While a roaring ball stirs up spirits inside, a boy and a girl meet on the sidelines – and fall in love at first sight. But because they belong to warring families, Romeo and Juliet's love may be immortal, but it is above all forbidden.

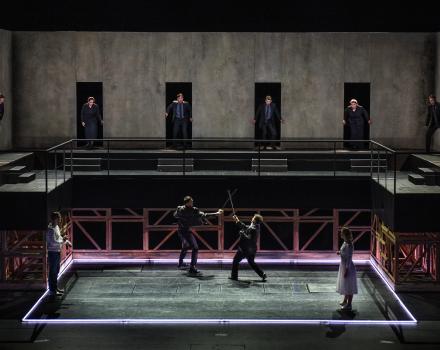

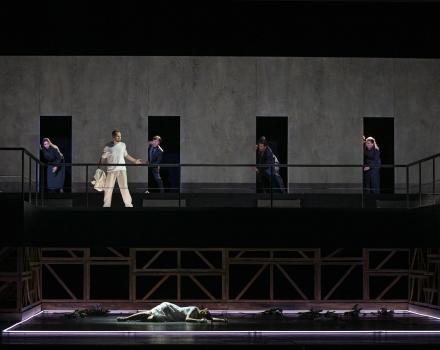

The chamber opera by the German-Baltic composer Boris Blacher, written in 1943, condenses Shakespeare’s famous tragedy to its essence: the fate of Romeo and Juliet. Scenic miniatures conjure a foggy world hostile to love. Characters occasionally materialise like ghostly apparitions, while a Brechtian chansonnier comments with humour and with harshness on the failure of the greatest love story of all.

Cast

Chansonnier | Florian Simson |

|---|---|

Romeo | Jussi Myllys |

Julia, Count’s fiancée | Lavinia Dames |

Lady Capulet | Katarzyna Kuncio |

Capulet | Günes Gürle |

Tybalt | Andrés Sulbarán |

Benvolio | Beniamin Pop |

Amme | Renée Morloc |

Musicians | Peter Nikolaus Kante, Steffen Weixler, Klaus Pütz |

Choir - Soprano | Anna Elisabeth Hempel*, Diana Klee* |

Choir - Alto | Ekaterina Aleksandrova**, Karolin Zeinert* |

Choir - Tenor | Sander de Jong**, Bohyeon Mun* |

Choir - Bass | Josua Guss*, Andrei Nicoara** |

| ... | |

Music | Boris Blacher |

|---|---|

Conductor | Christoph Stöcker |

Director | Manuel Schmitt |

Sets | Heike Scheele |

Lighting | Thomas Tarnogorski |

Costumes | Heike Scheele |

Text | William Shakespeare |

Chorus Master | Gerhard Michalski |

Violin 1 | Henry Flory |

Violin 2 | Johannes Heidt |

Viola | Annelie Haenisch-Göller |

Violoncello | Friedmann Dreßler |

Double bass | Max Dommers |

Flute | Sarah Heemann |

Bassoon | Jens-Hinrich Thomsen |

Trumpet | Antony Quennouelle |

Piano | James Williams |

| ... | |

Video

The story

Two households, both alike in dignity,

In fair Verona, where we lay our scene,

From ancient grudge break to new mutiny,

Where civil blood makes civil hands unclean.

From forth the fatal loins of these two foes

A pair of star-cross'd lovers take their life;

Whose misadventured piteous overthrows

Do with their death bury their parents' strife.

The fearful passage of their death-mark'd love,

And the continuance of their parents' rage,

Which, but their children's end, nought could remove,

Is now an hours' traffic of our stage;

The which if you with patient ears attend,

What here shall miss, our toil shall strive to mend.

Insights

On the battlefield of fate

Bringing world literature's greatest love story to the theatre stage in times of Covid-related social distance sounds like a daring undertaking. After all, isn't it precisely Romeo and Juliet's will to love, defying all odds, overcoming all social distances, transcending all boundaries, to which painters, poets, composers and filmmakers have paid homage in numerous adaptations of the material and which elicits secret sighs of longing even from hardened detractors of Romanticism?

‘Oh, never was a story of more woe than this of Juliet and her Romeo’, one could, in the words of its creator William Shakespeare, weep for the current theatrical fate of the ‘star-crossed lovers’, whose attempts at reuniting are currently thwarted not by their opposing parental homes but by the yardstick. The love plant cannot thrive on a freshly disinfected stage floor.

So no happy ending for Romeo and Juliet in these sterile times? It's not that simple. It does not do justice to Shakespeare's drama to try to reduce it to the tragic teenage love of two youths who have barely outgrown their infancy. The theme of this immortal material is not love, but its prevention by fateful circumstances. And what could be more topical?

In the bloody conflict between the Veronese noble dynasties Montague and Capulet, the young generation, through no fault of its own, is caught up in the maelstrom of an all-consuming hatred, the cause of which no one remembers. The particular tragedy of Juliet and Romeo lies in the fact that they only learn of each other's enemy identity when they have long since fallen hopelessly for each other: ‘I saw too soon, whom I knew too late!’, Juliet sums up dejectedly after the chorus has informed her of Romeo's true identity. The further course of the plot also reads like the test arrangement of a cruel deity. The more desperately the couple tries to escape the battleground of their family feud, the more mercilessly fate strikes back: even as they are getting to know each other at a Capulet party, the raging fury of Juliet's cousin Tybalt leaves no doubt that this story will end fatally. And indeed: no sooner have Juliet and Romeo decided on their future together than Romeo is drawn into a murderous confrontation against his will, in the course of which he stabs Tybalt and is forced to flee Verona. All efforts to defy fate and assert the utopia of a life together seem to be thwarted by higher fairy tales. Shakespeare leaves no doubt: there is no escape for the lovers from this catastrophe, for the worst (the death of love) must first occur for the hostile parties Montague and Capulet to understand the futility of their quarrel.

The power of fate is also the all-defining theme of Boris Blacher's Romeo and Juliet, which was written between 1943 and 1944 (but not premiered until 1947) and can be seen as a direct commentary on the horrors of the catastrophic world war, in which loving the enemy was often enough still punished by death.

Musically, Blacher's opera is directly in the musical tradition of Orff's pupil Heinrich Sutermeister, whose Romeo and Juliet was premiered at the Semper Opera in Dresden in 1940. Sutermeister's work already shows tendencies towards the lyrical abridgement of the Romantic orchestral apparatus, which he admittedly still pointedly alternates with opulent sound passages.

Blacher takes the sparseness of means to the extreme three years later during the war. The bombing of the German opera houses and a life-threatening lung infection are the formative events that give his version of Romeo and Juliet its dramaturgical and musical character. The omnipresence of death, even in the seemingly happy moments of life, gains a threatening presence through the Allied bombing raids. The extent to which this theme must have captivated Blacher is also evident in his adaptation of the Romeo material.

From the classic German translation by August Wilhelm Schlegel and Ludwig Tieck, the composer distilled scenic miniatures that radically reduce the Shakespearean drama to the powerless lovers in the face of their doom. Any episodes or characters that did not directly advance the tragedy of the two protagonists were eliminated from the plot. In keeping with the uncompromising conciseness of the scenes, Blacher created a score that ‘in its austerity is reminiscent of a small miracle’ (H.H. Stuckenschmidt). Like a haiku, the composer sketches with sparse instruments - a string quintet, flute, bassoon and trumpet make up the entire orchestral apparatus - sometimes developed from a single musical motif, building on it and circling around it, in its scenic miniatures, the love- and life-hostile world of fog through which Romeo and Juliet move. Other characters occasionally materialise like ghostly apparitions, only to disappear again just as suddenly as they came after fulfilling their dramaturgical function.

The chorus is the master of this universal realm of fate, which Blacher introduces as the third protagonist in the arrangement of the play. With text parts of characters who drive the action, such as the potion-administering Father Lorenzo, the Nurse or Romeo's friend Benvolio, the eight-member chamber ensemble oscillates flexibly between the role of a sympathetic observer, catalyst of action or indifferent commentator of the tragic events - without, of course, ever showing any willingness to show Romeo and Juliet the predefined path out of their downfall.

Depending on the musical treatment of the chorus in particular, the entire sound character of Romeo and Juliet can change in astonishing ways. Some of the few recordings available of this operatic rarity recall in their accuracy and transparent transparency the Apollonian tonal language of a Frank Martin, whose secular oratorio Le vin herbé was premiered only a year before Romeo and Juliet and must have been known to the Blacher. Other recordings of the work, especially from the English-speaking world, focus less on immaculate sound purity and more on a rougher, more characteristic interpretation in the style of Kurt Weill, in which the individual voice does not have to subordinate itself to the collective.

The most peculiar feature of this opera, rich in peculiarities, is also in the Weillian tradition: in three piano-accompanied chansons, a chansonnier splinters the delicate pathos of the rest of the score with laconic summaries of the dramatic events in Brechtian style. The subtle irony of the cabaret numbers reveals Boris Blacher's alienation at Shakespeare's moral verdict that it was too much love that brought about Romeo and Juliet's doom.

This score, which ‘conceals more than it says’ (H.H. Stuckenschmidt), defies any clear scenic definition in its compressed nature, but gives the opera-goer the opportunity to form his or her own fantasy of the tragic events.

Adapted from Anna Grundmeier

Gallery