Metastasio - 28 opera librettos and still counting

Sebastian F. Schwarz examines the legacy of the librettist Metastasio, the wordsmith of Achille in Sciro, Catone in Utica and at least 26 other works.

The man we know today simply as Metastasio was born in Rome in 1698 as Pietro Antonio Domenico Bonaventura Trapassi. The boy’s poetic and oratorial talent was soon discovered by Giovanni Vincenzo Gravina, then director of the Pontifical Academy of Arcadia, who adopted him and offered him a formal education and exposure to the highest intellectual circles of Rome and Naples. He also changed his last name Trapassi to its Greek equivalent: Metastasio. Pietro’s education, the obligatory studies of law aside, included a comprehensive training in Latin and Greek and the ability to translate the classical works into poetic modern Italian – a skill which laid the foundation for Metastasio’s entire professional future.

1720 marked the formal beginning of his operatic career when the 22-year-old transformed an episode from Ariosto’s Orlando furioso into the serenade Angelica e Medoro to be put to music by Nicola Porpora for the birthday celebrations for Empress Elisabeth Christine. This was also the beginning of another world-altering musical career: the debut of a pupil of Porpora’s, the castrate Carlo Broschi, soon world famous as Farinelli. Their first collaboration started a lifelong friendship between Metastasio and Farinelli (who called his friend his dear twin and who commissioned new works from him even 40 years later for the Spanish Court). The soprano Marianna Bulgarelli, also part of this historic double-debut, took Metastasio under her wing and introduced him to composers like Leo, Vinci, Scarlatti, Hasse, Marcello or Pergolesi. Between her and Farinelli, Metastasio received the best musical and vocal education and soon he would be working with the greatest singers and composers of his time, eventually leading to an invitation from the imperial court in Vienna.

‘Il cantante Farinelli con amici’ by Jacopo Amigoni - From left to right: Metastasio, Teresa Castellini, Farinelli, Amigoni.

From 1730 Metastasio succeeded the Venetian Apostolo Zeno as imperial poet (poeta cesareo) at the court of emperor Charles VI and later Maria Theresa, making Vienna his home until 1782, for the remaining 52 years of his life. He continued to write opera librettos into the mid 1740s and then concentrated on the smaller format of serenades (or feste teatrali) into the 1760s when he more or less retired both, from creative work and from society, reducing his radius of social contacts to the inhabitants and his many illustrious visitors in his apartment building on Kohlmarkt, right across from the Imperial Castle and next to St. Michael’s where he remains buried to this day.

Metastasio’s thorough knowledge of history and literature (from classical to contemporary, from domestic to foreign) enabled him to successfully adapt their stories for the stage and to press them into the strict corsage of the conventions of the dramma in musica of the late Baroque style of the 18th century. The opera seria (as the genre was soon named to distinguish it from the contrasting and competing comical opera buffa) was deeply mythological or heroic in nature, performed all over Europe and beyond (with the notable exception of France), exclusively in Italian, predominantly in the court theatres in front of noble audiences expecting the protagonists to portray and express virtues they could claim to be mirroring their own.

Metastasio developed to perfection Zeno’s structure of ideal juxtaposition of secco recitative and da capo arias, each its own clearly confined form, each with its very specific role: the former with fewer rhythmic constraints, leaving room for the freer declamatory recitation, furthering dramatic action; the latter the strict corsage of the obligatory da capo aria, its repeated first section providing room for star-singer vanity-driven added ornamentation and vocal fireworks, making them the perfect vehicles to further singer careers.

19th century scholar and literary critic De Sanctis beautifully described the contributions of the two greatest librettists of the 18th century as Zeno providing the mechanism, the skeleton, being the architect of melodrama into which Metastasio breathed grace and life, being its poet.

A Metastasio libretto was on average made into almost 40 individual operas.

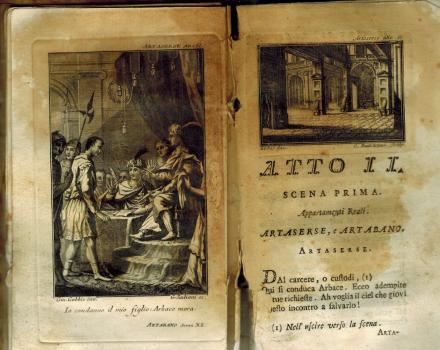

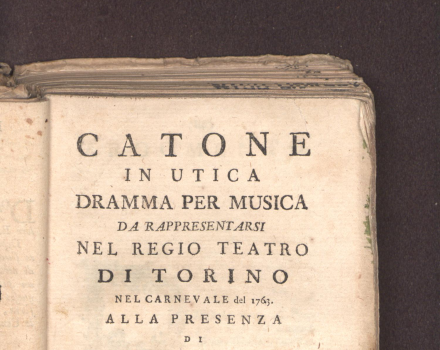

Metastasio’s heritage consists of 28 opera librettos, 8 librettos for oratorios, 36 for serenades and 37 for cantatas and is completed by a large number of songs, compliments, or works not intended for music like 32 sonnets, translations from Greek, spiritual poems or odes for weddings, as well as his over 2600 published letters. If these numbers are impressive in themselves, the wealth of musical production Metastasio’s poetry inspired in the composers of his century is simply staggering and made of him the by far most influential librettist not only of his but very likely of all times: these 28 opera librettos were set to music as unthinkable 1050 operas (that we know of today, there might still be many more stacked in some attic or in the chronically understaffed Italian libraries!). In other words: a Metastasio libretto was on average made into almost 40 individual operas, the most successful one being Artaserse which inspired 90 (!) composers to set this libretto to music. Maybe I can name 90 opera composers across the 450 years of the artform. But 90 from the 18th century alone? Artaserse is followed by Demofoonte (75), Didone abbandonata (70), Adriano in Siria (65), L’Olimpiade (60), La clemenza di Tito (50),… Catone in Utica was first set to music by Leonardo Vinci in 1728, Achille in Sciro by Antonio Caldara in 1736, each followed by at least 29 other composers.

Most of the 28 Metastasian librettos were put to music for the first time by Leonardo Vinci, Antonio Caldara or Johann Adolph Hasse, and later taken on by Porpora, Bononcini, Gassmann, Feo, Corti, Wagenseil, Vivaldi, Mysliveček, Salieri, Gluck, Haydn, Cherubini or Mozart, to name just a few. More than 360 oratorios are based on Metastasio’s 8 librettos for this genre and his 36 serenate (feste or azioni teatrali) translated into ca. 254 compositions. We currently know also of 37 cantatas with an unknown number of settings to music. These known musical works alone count to more than 1700 – one thousand and seven hundred - operas, oratorios, serenades and cantatas.

Though his work’s popularity with composers outlived him by far and his words continued to be put to music into the 1800s; from the 1760s the operatic world gradually changed and required a different kind of writing. With the Viennese premieres of his Orfeo ed Euridice (1762) and Alceste (1767), Christoph Willibald Gluck proposed a new style which reformed the artform and shaped opera for far more than just the next decades. Undoubtedly Gluck had a great professional appreciation of Metastasio as 20 of his 50 operas are based on his librettos. But by the 1760s the artform made a first important shift to place more musical importance on the dramatic aspects of the plots, making room for trios, quartets and ensemble or even chorus numbers, for accompagnato recitatives; leaving space for a freer rhythmic treatment of text while other languages started to play a role in opera.

Opera matured, grew out of its skeleton and required a revision of its architecture. But Metastasio’s contribution to the importance of the artform remains unquestioned and I fully expect untiring researchers to discover more operas based on his poetry.

Article by Sebastian F. Schwarz

February 2023